Fallen Leaders: Colonel Isaac Seymour, 6th Louisiana Infantry, Part 2

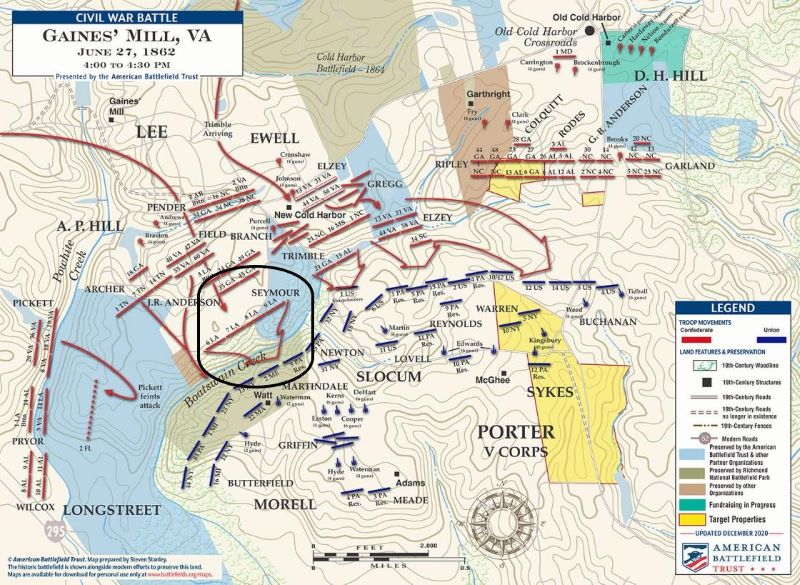

General Thomas Jackson’s tardy arrival to the Seven Days Battle meant that the 6th Louisiana Volunteers and Colonel Isaac Seymour (now in command of the entire Louisiana Brigade) missed the opening engagement at Beaver Dam Creek. They were, however, ordered to take the front of General Richard Ewell’s column as skirmishers. They would arrive on the field at Boatswain’s Swamp, also called Gaines Mill, on June 27th, 1862. The left of the Confederate line was sheltered in the woods, but the center and right would have to cross nearly open fields, descend the steep ravine covered in tangled vines and underbrush, wade across the creek, then ascend up the opposite slope to the entrenched Federals, all while under heavy fire. The terrain at Gaines Mill was formidable, compounded by the 96 Federal guns looming down upon the Confederates from three separate artillery lines across the slope. The battle was in full swing by the time Ewell arrived with his division, including the Louisiana Brigade.

Seymour’s brigade was hastily formed up in one of these open fields between Ewell and A.P. Hill’s divisions, just to the right of a road leading from New Cold Harbor and through the wooded ravine. With Colonel Seymour finally in command of the brigade and seated upon his large and spirited mare, he led the brigade forward. Dead and wounded fell all around as they were harassed by Federal sharpshooters. Lieutenant Walshe of the 6th Louisiana wrote, “When we were near enough, a charge was ordered, and we soon reached a creek, the crossing of which was difficult, as the enemy had felled timber to impede our progress.”[1] They crossed the creek and began their ascent up the slope when “a perfect hailstorm of bullets greeted our advance,” reported Private Handerson of the 9th Louisiana, “the intensity of the fire far exceeded all that we had experienced in the Valley.”[2]

The right wing of Union Brigadier General George Morell’s division poured down a deadly volley from his three lines of riflemen. The Louisianans were under relative cover in the swamp around the creek, but “many of us were wounded, and all within a space of thirty yards and that was as far as the brigade went,” according to Walshe.

One of the fallen was Colonel Seymour. The brigade became pinned down by the galling fire from the Federals. As he tried desperately to rally his men in the thicket of the swamp, he fell from his horse, shot in the head and in the body. Within moments, the “Old Man” was gone. About the same time, Major Roberdeau Wheat was also killed. With Taylor absent, and both Seymour and Wheat struck down, the brigade was without leadership. Another 9th Louisiana soldier recalled, “Now was the critical moment when a voice of authority to guide our uncertain steps and a bold officer to lead us forward would have been worth to us a victory. But none such appeared.”

Lieutenant Walshe, wounded in the leg during the advance, helped other men from the 6th Louisiana gather up their deceased colonel and bring him toward the direction of the creek. There, they laid beside Seymour’s body, bullets hitting the surface of the running water like a heavy rain all around them.[3] It wasn’t until the charge of Brigadier General John Bell Hood’s Brigade toward the center, supported by charges on the left and right, that the Confederates were finally able to pierce the Federal defenses atop the ravine.

The Louisiana Brigade lost 32 dead and 142 wounded, just a small portion of the 7,900 Confederate casualties of the day.[4] Though the position was carried and Brigadier General Fitz John Porter’s corps withdrew, the Louisiana Brigade could not feel proud for the accomplishment. They had lost their colonel and they knew they had not succeeded in the charge that was ordered for them.

General Richard Taylor later remarked upon having a “wretched feeling of guilt, especially about Seymour, who led the brigade and died in my place.” In a eulogy-like commendation of the old colonel, Taylor wrote in his memoirs, “Brave old Seymour! I can see him now, mounting the hill at Winchester, on foot, with sword and cap in hand, his thin gray locks streaming, turning to his sturdy Irishmen with ‘Steady, men! Dress to the right!’ Georgia has been fertile of worthies, but will produce none more deserving than Col. Seymour.” He added that Seymour was, “a man of culture, respected by all.”[5]

The official eulogy in his newspaper back in New Orleans would praise him as a “genial Southern gentleman” with “few or no enemies.” He was painted as a patriot in the twilight of his years, whose “motive that carried him to the field was simply duty… It was duty that placed him in front of danger at the battle of the Chickahominy; and, in fine, it was on the altar of duty that he offered up his life.”[6] William Seymour, his son, would be arrested and imprisoned for two and a half months for publishing the obituary of his father, as it rang of pro-Confederate commentary, which General Benjamin Butler had banned during his occupation of New Orleans.

Colonel Seymour’s body was initially transported to Lynchburg for burial, but was shortly after moved to Macon, Georgia where he had been editor of a newspaper prior to taking up residency in New Orleans. He is buried in Rose Hill Cemetery beside his wife and children. Henry B. Strong, a 40-year-old, Irish-born clerk from New Orleans became the new colonel of the 6th Louisiana. William Seymour would later leave New Orleans and became an aide to Brigadier General Harry T. Hays, who was given command of the First Louisiana Brigade on July 25, 1862.

The Louisiana Brigade would go on to fight in nearly all of the major battles and campaigns in the eastern theater, surrendering with Robert E. Lee’s army at Appomattox on April 9th, 1865. Their success and fame as the “Louisiana Tigers” came without Colonel Isaac Seymour by their side at major engagements like Chancellorsville or Gettysburg. However, it’s likely that the lessons these Louisiana recruits learned from their Colonel in the first year of the war stuck with them until the very end. His disciplinarian methods and fatherly deportment left an impression upon these men, endearing them to this old newspaper man from New Orleans who first commanded the 6th LA. He would never be forgotten as the veterans of his regiment looked back on those early years of the war, fondly remembering their “Old Man”.

Footnotes

[1] Walshe, “Recollections of Gaines’ Mill,” Confederate Veteran, vol . 7, p. 54

[2] Henry Ebenezer Handerson, Yankee in Gray: The Civil War Memoirs of Henry E. Handerson, Literary Licensing, 2011, p. 45, p. 96

[3] Walsche, “Recollections of Gaines’ Mill.”

[4] James P. Gannon, Irish Rebels, Confederate Tigers: A History of the 6th Louisiana Volunteers, 1861-1865, London, England: Da Capo Press, 1998, p. 81

[5] Richard Taylor, Destruction and Reconstruction: Personal Experiences of the Late War, Bantam Books, 1992pp. 91-92

[6] The Commercial Bulletin, New Orleans, July 30, 1862.

“I wouldn’t follow Jesus Christ up that hill now” – I paraphrase some Louisiana soldier after Wheat as struck down that day. Can be found in Terry Jones’ book in the Louisiana brigades in the ANV, which no doubt the author has on her bookshelf.

I haven’t read Taylor’s memoir yet, but I read in another book, which probably quotes his memoir, that Taylor said he was mortified when he was promoted to Brigadier General over the likes of Isaac Seymour who was older and more experienced than himself at soldiering. And of course Taylor was Jeff Davis’ former brother-in-law, which Taylor knew would cause some grumbles.

Ha! Totally missed part 1 where you write about Taylor taking over the brigade.

Nice post. Thanks.

Staggering losses! Greater than Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg. I have read that this Confederate advance might have been the largest one in the Civil War. The story of Colonel Seymour puts a face on the statistics. Thanks