Fallen Leaders: General Barnard Elliott Bee

Barnard Elliot Bee, Jr. appeared briefly in the saga of Civil War history. He died at the First Battle of Manassas on July 21, 1861, but not before attributed, immortal words had crossed his lips. Best remembered as the officer who gave General Thomas J. Jackson the sobriquet “Stonewall,” Bee’s actual intention of his words (or if he even said them) has been a matter of debate for decades.

Who was Bee—beyond the fallen officer who praised (or cursed) Jackson and the First Virginia Brigade? Looking closer at his life reveals a career of a military officer…and one who had crossed paths with man called “Stonewall” long before the battlefield near Bull Run.

Born on February 8, 1824, in Charleston, South Carolina, Bee grew up in his prominent Charleston family, enjoying the advantages of family lineage and wealth. When his parents moved to Texas in 1836 to explore the promise of that new republic, he stayed behind with extended family to further his education. Five years later, he entered West Point and spent the next four years studying and racking up demerits but managing to graduate thirty-third in a class of forty-one in the Class of 1845. Bee’s West Point years overlapped with Cadet Thomas J. Jackson from Virginia, but Jackson graduated in the Class of 1846. Bee joined the 3rd U. S. Infantry Regiment and went to Texas. In the Mexican-American War, he was brevetted to first lieutenant for his actions and wounding at the Battle of Cerro Gordo and brevetted captain after the Battle of Chapultepec.

Following the war, Bee joined the garrison at Pascagoula, Mississippi, serving as adjutant. Six years of frontier service (1849-1855) took him to New Mexico Territory. In 1855, he transferred to the 10th U.S. Infantry at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. While at Fort Snelling, Bee married Miss Sophia Elizabeth Hill and records suggest they had two children who did not live to adulthood.** During 1857 and the Utah War, he took command of the Utah Volunteer Battalion and brevetted to lieutenant-colonel. He served at Fort Laramie in Wyoming Territory and commanded the garrison there for a short period in 1860.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina—Bee’s home state—declared secession from the Union. Bee took his time making his decision, submitting his resignation from the U. S. Army on March 3, 1861 and then journeying to Charleston. He was quickly chosen as the lieutenant colonel of the 1st South Carolina Regulars.

Troops gathered in northern Virginia, expectantly waiting to see where the Yankees would start the invasion of that state which had gained importance in the Confederacy both by previous history and the relocation of the Confederate capitol to Richmond. On June 17, 1861, Bee received a transfer and appointment to brigadier general, giving him command of the third brigade in General Joseph Johnston’s Army of the Shenandoah. His brigade included the 4th Alabama, Companies A and K of the 11th Mississippi, 6th North Carolina, and the Staunton Artillery.

In early July, Bee had been notified to prepare to support Jackson’s brigade in the fight around Falling Waters, but the affair concluded before he arrived. On July 18, 1861, a telegram arrived in the lower Shenandoah Valley, summoning Johnston and his force to join Beauregard near Manassas Junction. Although he didn’t know it, General Bee had just days left to live.

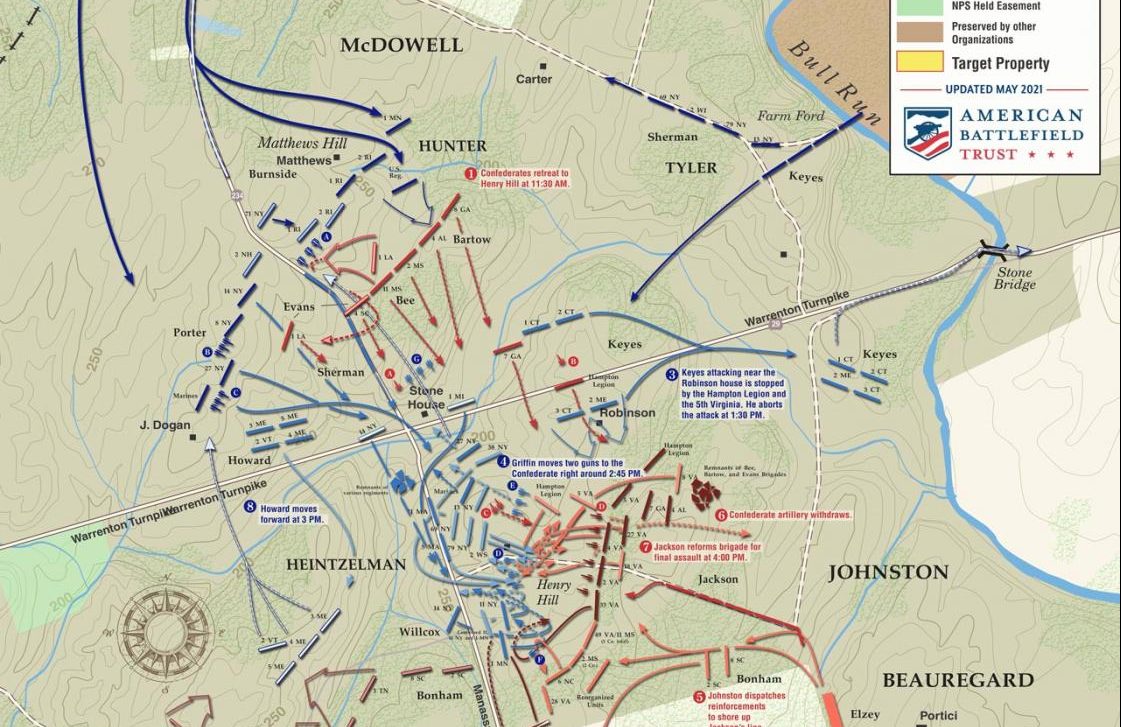

The first major battle of the Civil War exploded on July 21, 1861, and General Bee and his brigade took an early beating on the battlefield. Send to reinforce General Nathan G. Evans in a defense north of the Warrenton Turnpike, Bee positioned on Matthew’s Hill, not far from the Stone House. However, the Federals outnumbered Bee’s brigade and, along with General Bartow’s brigade to his right, he was forced to abandon the position around 11:30am. Retreating through the low ground between Matthew and Henry Hills, Bee struggled to keep his regiments in order as they scurried for cover near Young’s Branch on the right of the First Virginia Brigade which had held position on Henry House Hill without coming to the aid of the retreating Confederate units.

That is the complimentary version of what happened, painting Jackson as the inspiring hero that Bee used bolster his soldiers’ courage again. Other accounts suggest that Bee may have been frustrated by Jackson’s lack of support, and exclaimed something along the lines of “There stands Jackson like a damned stone wall!” cussing his former classmate for refusing to move to support the retreating brigades.

(Perhaps there’s also an idea — however far-fetched— that perhaps both the cursing and the compliment could be true. Bee could have been angry and raining imprecations on Jackson as his brigade broke and ran, and then realizing Jackson’s plan after their conversation, gained an admiration for him?)

Whatever the exact circumstances, phrasing, and meaning of Bee’s words on the Manassas battlefield, the part that mattered for the building of the legend was the word “stonewall.” Bee was never able to clarify his own interpretation or tell his side of the story of that July day.

Shortly after rallying his men, Bee was mortally wounded in the abdomen. Carried away from the fighting to a log hut, his final thoughts and any last words would likely have been for his family or his cause before his death on July 22, 1861.[iv]

As one of the first generals to die in the Civil War, Bee’s fall was quickly noted by both sides and memorialized by the Confederacy. His words (or the interpretation of them) helped to launch the famed name for Jackson and the First Virginia Brigade: Stonewall. Today, that is what Bee is most remembered for contributing to Civil War history.

However, in December 1861, the South Carolina House of Representatives passed resolutions in honor of General Bee and their explanations shed light on how his death was viewed just months after it happened:

The battle of Manassas, which vindicated and sustained the character of our Southern people for valor, and of their leaders for military capacity, however glorious, in a national point of view, have been its results, has left some recollections upon which we of South Carolina cannot dwell without the most painful emotions.

Not the least mournful of these memories is that connected with the death of General BARNARD ELLIOTT BEE.

But the gloom of grief is even here relieved by the halo of glory which marked the close of his mortal career. The cypress wreath which Carolina weaves for her fallen son, is thickly interwoven with the laurel leaves of victory. He fell in the very hour of triumph after having long held at bay five times as many of the enemy as he numbered in his own gallant command. His mortal wound brought with it, to his noble mind, no despondent thoughts, and having spent the day of life gallantly as a soldier, he met his night of death, if not with welcome—for he had every motive to live—at least with noble resignation, and exclaimed, almost with his last breath, that he died happily, inasamuch as he died in the arms of victory. It was a noble sentiment—the sentiment of a patriot and hero, who merged self in his country—of a soldier to whom honor was dearer and more cherished than life….

His first and his last blow was struck on the bloody plains of Manassas—that Marathon of the South—where brave hearts and strong hands were enabled to stay the onward progress of a hostile army, and where the successful resistance of Southern troops to a horde of Northern vandals and mercenaries brought with it not only a glorious victory for the present, but a prestige of victory for all time to come.

When, in the very thickest of the fight, he exclaimed to his devoted troops, “There, men, stands General Jackson, like a stone wall” (whence the brigade of that heroic Virginian has since received the appellation of the “Stone Wall Brigade) he expressed, in reference to one portion of our army, what might well be said of the whole, for against the impetuosity of an enemy flushed with the false hope of a speedy triumph to be derived from superior numbers and all the advantages of well trained and perfectly equipped troops, the soldiers of the South stood between the incursions of their oppressors and their native soil like a wall of adamant, which could only be penetrated by its entire demolition.

Here it was, in the defense of this important position, that our gallant countryman fell—fell for Carolina, which he loved so well—fell at the very moment when, though his life might have been the most useful to his country, his death was most glorious to himself….[v]

Notes and Sources:

**I’ve spent some time trying to track down more about Bee’s marriages and family. According to FindAGrave, he might have married in 1850 and that first wife died in 1854; however, I have not found solid sourcing in Ancestry or other genealogical references to support this. Sophia Elizabeth Hill is more readily cited as his wife by 1855; according to FindAGrave, they had two children who did not live past toddlerhood. Again, I have not yet found additional citations for this in other sources after a quick genealogical search. Sophia remarried after Bee’s death, and her last name changed to Thurston. Perhaps with a little more time, I’ll be able to better provide better sourcing for Bee’s family life and it could be a follow-up blog post?

[i] James I. Robertson, Jr. Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend. (New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1997) 264.

[ii] Ibid., 264.

[iii] Ibid., 264.

[iv] Texas State Historical Association, Barnard Elliott Bee, Jr. https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/bee-barnard-elliott-jr

[v] The Charleston Daily Courier, December 23, 1861. (Accessed at Newspapers.com)

Excellent article!

Thanks for the insight on the potential “alternative” meaning of “Stonewall”. I had not heard that non-traditional interpretation before

Ironically, he is buried in the same graveyard in Pendleton, SC as Floride Calhoun.

I’ve always thought the alternative meaning of “stonewall” was hooey. The brigade would not have adopted it as a nickname had they thought it an insult.

I spoke with a Bee descendant about this a few months ago. He says the Bee family has always believed Barnard Bee was upset with Jackson, not praising him.

Tom Crane

It is my understanding that the Stonewall Brigade (33rd Va) came forward to the Henry House in an attack on Griffith’s Artillery setting up there and were busy in repulsing a Union counterattack at the time Bee was retreating into the area. Maybe I got it wrong.

And I just found out that Barnard Bee Jr is my 9th cousin.

How did you go about that how did you ? If you don’t mind me asking my papa always said we did and that son of the Confederacy tried to recruit him and my father and they turned him down because of that was their choice. I’m a history buff so I’m trying to figure it out

I’m Robert Leonard Bee III

Hope you have a great day and you have my stepmother’s name beautiful name