Finding Miss Susie

If studying history has taught me anything, it’s that everything is connected. Places, people, and events that shaped the nation did not occur in a vacuum. The soldiers and civilians we read about did not exist in just one place at a certain time. They lived on – mostly – to travel, have relationships, and pursue happiness in their own ways. Like us, they made connections and left an impact on the world that echoes through time. One such connection hit me in the face quite unexpectedly during one of my recent travels.

The Reconstruction Era National Historical Park was established rather recently in 2017. In Beaufort, South Carolina, the rangers and historians of the park are dedicated to telling the story of reconstruction during and following the Civil War. Beaufort became ground-zero for the reconstruction experiment after its capture in November of 1861. The majority of the white population fled after the arrival of the Federals, fearful that they would be executed for treason. This left the enslaved population in the hands of an army that didn’t know what to do with them.

Numerous charitable projects popped up through Beaufort and on the islands, namely in education for those now considered “contraband.” The collective endeavors of philanthropists from New York City, Boston, and Philadelphia became known as the “Port Royal Experiment” and made tremendous headway in establishing political, social, and economic reform in the Beaufort area.

Under the Militia Act of 1862, formerly enslaved men were able to enlist and take up arms in the cause that had paved the way for their freedom. A training camp was established in the Fall of 1862 on the grounds of John Joyner Smith Plantation. Camp Saxton, named after General Rufus Saxton, governor of the Department of the South from 1862 to 1865, became a hub for black recruitment. Charged by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, Saxton was to “arm, uniform, equip, and receive into service… such number of volunteers of African descent… not exceeding 5,000.” Soon, the 1st South Carolina Infantry was formed and trained at the site between November of 1862 and January of 1863 before being mustered into service.

Perhaps the most famous of the events that took place at Camp Saxton was the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation on New Years Day, 1863. A crowd of 5,000 assembled in a stand of live oak trees at Camp Saxton to listen to the words of freedom. During the ceremonies, an unknown elder began singing “My Country Tis of Thee” and the crowd of free men and women joined in. One woman in attendance was Susie King Taylor, a laundress who had arrived to the camp the previous October and later wrote that she had several uncles and cousins in the 1st South Carolina Infantry, as well as a husband in Company E.[1]

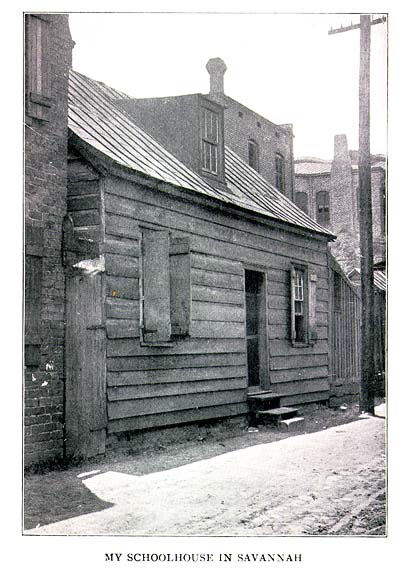

Prior to her arrival at Camp Saxton, Susie had taught illiterate children and adults on St. Simon’s Island, having learned to read as a young enslaved girl in Savannah, Georgia. Under the care of her free grandmother, she and her brother would wrap their books in paper and were sent to a Mrs. Woodhouse for their lessons.[2] This illegal education afforded her opportunities to help her family and community, including writing passes for her grandmother so she could be on the streets after nine o’clock.[3] After the capture of Fort Pulaski in April of 1862, Susie – at the vulnerable age of thirteen – and her family were taken by her uncle to St. Catherine Island, then to St. Simon’s Island where “to my unbounding joy, I saw the ‘Yankee’” for the first time. There, she impressed the officers with her ability to read and write and was given charge over forty students before she followed future enlistees under Captain C.T. Trowbridge to Camp Saxton. She worked as a teacher, laundress, and nurse for the men of the 1st South Carolina Infantry – later designated the 33rd US Colored Infantry.

Susie remembered Emancipation Day with fondness and pride:

“It was a glorious day for us all, and we enjoyed every minute of it, and as fitting close and the crowning event of this occasion we had a grand barbeque. A number of oxen were roasted whole, and we had a fine feast. Although not served as tastily or correctly as it would have been at home, yet it was enjoyed with keen appetites and relish. The soldiers had a good time. They sang or shouted ‘Hurrah!’ all through the camp, and seemed overflowing with fun and frolic until taps were sounded, when men, no doubt, dreamt of this memorable day.”[4]

Today, a visitor can stand in the same space Susie stood as the promise for a free and hopeful future was read aloud to the spectators that January day in 1863.

After the war, Susie and her husband Edward returned to Savannah, Georgia where she opened a school on Oglethorpe Avenue for black children. She kept twenty students and received a dollar for each every month.[5] Edward struggled to find work, despite his proficiency at carpentry, and had to take a job unloading shipping vessels. Susie taught for almost a year before a free school, the Beach Institute, opened its doors and took a number of her students. That September, she lost her husband while also expecting their first child. With the assistance of her brother-in-law, she was able to open a night school teaching adults, until the Beach Institute offered night classes as well and she lost her pupils again to the lure of free education.

In 1872, Susie was able to receive a claim of one hundred dollars for her husband’s bounty from the army and in the fall began work as a laundress, an occupation she knew just as well as teaching. She was employed by Mrs. Charles Green of Savannah.[6]

History buffs may recognize this name, but may not instantly connect it with Susie’s story. Charles Green was an Englishman who had arrived in Savannah in 1833 and quickly made his fortune as a successful cotton merchant and ship owner. His home was built in 1853 in the iconic Gothic Revival style – a major departure from the customary Greek Revival style of Southern mansions of the era. Weighing in at $93,000, the home was designed for luxury and opulence, filled with furniture from all across Europe. Even today, the interior of the home impresses its visitors with its ornamental crown moldings and decadent patterned wallpaper. No expense was spared in creating a grand and elegant home that epitomized the wealth and elitist lifestyle of the Green family.

The Green House’s claim to fame is not for Susie’s employment there, but for the arrival of General William T. Sherman in December of 1864. Having completed his March to the Sea from Atlanta, Sherman captured Savannah and was invited by Mr. Green to establish his headquarters in his home adjacent to Madison Square. In the upstairs study, Sherman penned the infamous telegram to President Lincoln reading, “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift the city of Savannah with 150 heavy guns and plenty of ammunition and also about 25,000 bales of cotton.”[7]

The home is maintained by the St. John’s Episcopal Church – conveniently located next door – and remains a National Historic Landmark, open for tours to the public. Today, visitors not only have the opportunity to stand in the room where the telegram was written, but also walk the halls that Susie King Taylor had once walked. They can climb the stairs she might have climbed on a daily basis, and peer out the windows she might have gazed through between her chores. One must wonder if she knew where she was working and of its significance, and what she might have thought about standing in the same space General Sherman once occupied.

Not much is known about the two years Susie was with the Green family, apart from what’s written in her memoirs, which only chronicles a trip she took with the Greens to Rye Beach when she took the place of their cook and won a prize at a fair. In 1874, she would move to Boston, Massachusetts and continued domestic employment. She passed away October 6, 1912 in Boston and is buried in Mount Hope Cemetery. Before she died, she penned a lasting legacy in her memoirs, “Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops Late 1st S. C. Volunteers” published in 1902. It remains one of the few narratives written by a formerly enslaved African American woman and gives readers a look into her life and the history she endured. Her candid reflections on the times she lived in has become a valuable primary source for historians over the decades.

So few places that had been touched by Susie King Taylor can be easily found today. However, thanks to the preservation efforts at the Reconstruction Era National Historical Park and the caretakers of the Green-Meldrim House in Savannah, we can walk in the footsteps of a courageous woman who made a difference to history in her own humble way.

Footnotes

[1] Susie King Taylor, ed. Patricia W. Romero, Reminiscence of my Life in Camp with the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops, Late 1st South Carolina Volunteers. A Black Woman’s Civil War memoirs, New York, Markus Wiener Publishing, 2007, p. 42

[2] Ibid. p. 29

[3] Ibid. p. 31

[4] Ibid. p. 49-50

[5] Ibid. p. 124

[6] Ibid. p. 127

[7] Telegram from Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman to President Abraham Lincoln, presenting the city of Savannah as a Christmas gift, December 22, 1864.(National Archives Identifier: 301637 ); Series: Telegrams Sent by the Field Office of the Military Telegraph and Collected by the Office of the Secretary of War., 1860 – 1870; Records of the Office of the Secretary of War; Record Group 107; National Archives.

Great article! I love coastal Carolina and Georgia. It is such a beautiful area and full of great history. I’ve been to Fort Pulaski, but never the Green-Meldrim House and I’ve never heard of Susie King Taylor. I’m sure her memoir is a good read though. I went to boot camp at Parris Island, near Beaufort, and while there I remember some of the barbers speaking to each other in Gullah, while buzzing down the stubble on our heads every week or so. Knowing about the freedman’s coastal enclaves even then, hearing them speak the language, for me, was almost like being in a museum and looking at a relic of the war. Instead of being a physical artifact though, it was a linguistic one.

Thank you. A completely new chapter in my understanding of Sherman’s 1864 Campaign.