Reconsidering Barlow’s Knoll

The First Division of the Eleventh Corps of the Army of the Potomac arrived in Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 1, 1863. Only 29 years old, Brigadier General Francis Barlow commanded the division. He resented the men he commanded, writing home of his “indignation & disgust of the miserable behavior of the 11th Corps,” unfairly blaming them for the loss at Chancellorsville. There, the corps was assigned a position that they could not hold against overwhelming Confederate forces. The same thing would happen again on July 1.

The First Division of the Eleventh Corps of the Army of the Potomac arrived in Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 1, 1863. Only 29 years old, Brigadier General Francis Barlow commanded the division. He resented the men he commanded, writing home of his “indignation & disgust of the miserable behavior of the 11th Corps,” unfairly blaming them for the loss at Chancellorsville. There, the corps was assigned a position that they could not hold against overwhelming Confederate forces. The same thing would happen again on July 1.

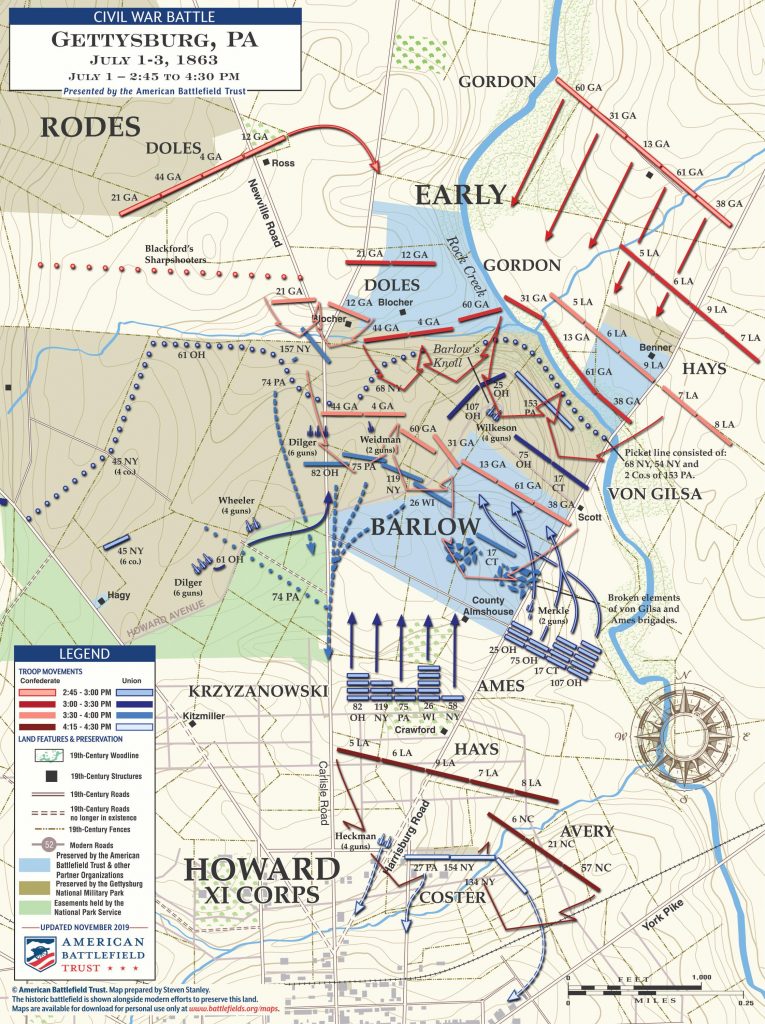

As the division moved into the fields north of town, Barlow spotted Blocher’s Knoll, which now bears his name, a small, raised hill one mile from his assigned position. Without orders, he moved his division to take it. Major General Carl Schurz, acting commander of the corps, had ordered him to hold Third Division commander Brigadier General Alexander Schimmelfennig’s flank. Without telling his commander, Barlow decided to advance his line. Technically he may have followed the letter of the order, as he deployed near Schimmelfennig’s skirmishers, but it absolutely ignored the intent. This new position was significantly longer than his initial one. This is the only real raised position in the area, but new Confederate arrivals would soon make this position untenable.

Barlow ordered Col. Leopold von Gilsa’s small brigade of 900 men to take the heights. 400 New Yorkers from the 54th and 68th New York advanced as skirmishers, and the large, 500 man 153rd Pennsylvania, a 9-month regiment nearing the end of their enlistment, was held in reserve, though some companies joined the New Yorkers on the skirmish line. First, they had to push back the Confederates skirmishers and sharpshooters on the knoll. The Union troops did so, forcing them into the woods and across Rock Creek. Then, they formed their defensive position.

Once formed, their line consisted of skirmishers set along the waters of Rock Creek and Blocher’s Run. There weren’t enough men, so they were spread out to about one man every two yards, and the dense underbrush made it difficult to fire at oncoming Confederates until they were dangerously close. This thin line was supported by a rear line that bent to an angle along the knoll. Brigadier General Adelbert Ames’ brigade deployed behind the knoll as support. Exposed Union forces soon came under fire by Confederate artillery, then Brigadier General John Gordon’s infantry brigade launched their assault on the Union lines.

Gordon wrote of his attack on the creek: “Moving forward under heavy fire over rail and plank fences, and crossing a creek whose banks were so abrupt as to prevent a passage except at certain points, this brigade rushed upon the enemy with a resolution and spirit, in my opinion, rarely excelled. The enemy made a most obstinate resistance until the colors of the two lines were separated by a space of less than 50 paces, when his line was broken and driven back.”

Despite the negative reputation the Eleventh Corps had acquired, Private Nichols of the 61st GA also commented on the obstinance of the Union troops, stating “We had a hard time moving them. We advanced with our accustomed yell, but they stood firm until we got near them. They then began to retreat in fire order, shooting at us as they retreated. They were harder to drive than we had ever known them before. Men were being mowed down in great numbers on both sides.” It’s worth noting Confederate command and foot soldiers both recorded the strong fight that the outnumbered Union soldiers made. Barlow had ordered artillery from Lieutenant Bayard Wilkeson’s battery to support the knoll, but it was not enough. As Gordon attacked the Union line, Brigadier General George Doles’s brigade, numbering another 1400 men, then assaulted the left.

As the Georgians approached, the rest of the 153rd Pennsylvania was rushed up to reinforce the line. Now, Von Gilsa’s 900 men faced nearly double their number, holding a skirmish line rather than a compact line of battle. Slowly but steadily, this outnumbered brigade was forced to retreat. As one soldier of the 153rd retreated through the woods, he remembered seeing the Union dead: “They were piled in every shape, some on their backs, some on their faces, and others turned and twisted in every imaginable shape.” They had paid a terrible price.

Then Ames’s reinforcements attempted to hold steady in vain. Soon, they too were in retreat. More Confederate troops had arrived from the east, and now Barlow’s troops were not only greatly outnumbered but now under attack on two sides. In this chaos, Barlow fell to the ground grievously wounded and was left behind. Allegedly, John Gordon himself spoke to the wounded Barlow and found him aid. The story of Barlow and Gordon reuniting post-war, both thinking the other had died, is one of the more famous anecdotes of Gettysburg, though how truthful these tales are is uncertain.

As Barlow’s brigades fell back, other units from the Eleventh Corps were thrown into the fray, forming new positions. One by one, they too were overwhelmed. One Union brigade commander rode the line during the battle, describing his men as “sweaty, blackened by gunpowder, and they looked more like animals than human beings.” To him the “portrait of battle was the portrait of hell.” Finally, scattered remnants of many groups rallied into one last position near the almshouse. Though a worthy effort, the final line collapsed. Ames recalled “The whole division was failing back with little or no regularity, regimental organizations having become destroyed.” As shown through these firsthand quotes, the men of the Eleventh Corps had done their best to hold, but Barlow had put them in an impossible situation, deploying them along too long a line in a position exposed to attack.

Von Gilsa’s brigade was spread thin and assaulted on two flanks, and they had put up as much of a fight as was reasonably possible. They had been unable to hold the knoll and had been defeated. Attempts to stem the tide had failed, as two more brigades fell to the Confederate onslaught. Now, the entire right of the Eleventh Corps had collapsed into disorder. Despite this valiant and obstinate effort, Barlow’s Division was unable to hold this position. At the knoll, they valiantly attempted to erase the stain of their defeat at Chancellorsville, only to be defeated and add to the unjust reputation their corps acquired in 1863. Perhaps on your next visit to Gettysburg you’ll come visit this less popular portion of the battlefield or venture down the knoll to the banks of the creek to one of the least visited monuments on the field and consider their efforts.

_______

References

Regimental Files, Gettysburg National Military Park Library.

David G. Martin. Gettysburg July 1. Da Capo Press, 2003.

Harry W. Pfanz. Gettysburg: The First Day. University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

John C. Fazio. “The Barlow-Gordon Controversy.” Gettysburg Magazine 41, July 2009.

James S. Pula. Under the Crescent Moon with the XI Corps in the Civil War: Volume 2 From Gettysburg to Victory 1863-1865. Savas Beatie, 2018.

October is a great time to visit Barlow’s Knoll. You may find the weather like a July day, but the crowds of tourists are none but the purists. Journey down Barlow’s Knoll from the monument(s) atop to Rock Creek below. (I’d recommend thornproof pants and waterproof footwear.) You’ll find Rock Creek’s description quoted in the article to be accurate. You may see a few deer scrambling away from the sight of a rare explorer. Then try running up Barlow’s Knoll from the Confederate point of view.

October would certainly be an easier time! I generally made the trek to the creek in June or July, and while there was never anyone else around, it was a bit overgrown. The “trail” was just barely visible in summer, so fall or winter might make it easier to find the monument.

You can find an informative and thorough evalaution of the Barlow-Gordon relationship in “The Boy General. The Life and Careers f Francis Channing Barlow.” (2003.)

They’re certainly both characters in their own ways, Barlow and Gordon.

For a very enjoyable and interesting albiet fictionalized description of the battle at Barlows Knoll read Ralph Peters book “Cain at Gettysburg.” i love that book and have reread it multiple times. As Krzyzanowski watches Barlow’s command advance to the Knoll unsupported, Der Kryz comments to shimmelfinnig: “We are in the shit now. Now we have to rescue that fool.” or something to that effect. it is probably fiction but its a great line. the book foscuses on the union german regiments north of Gettyyburg and the Iron Brigade fight in Herbst woods .on Day 1. its a great description of both fights.

Interesting! Though the particular choice of words made be fiction, sounds like he got the sentiment right. Those Union German troops have an awful day on July 1, and get a lot of unfair blame.

I was looking at Cain at Gettysburg on Amazon and discovered a new Ralph peters civil war historical novel called “Darkness at Chancellorsville”. I am so excited! I ordered it immediately . I can’t wait to read what words Col . Peters puts in the mouths of stonewall Jackson’s and Fightin Joe hooker. Der Kriz was there with the German brigades as was the boy general Barlow . It’s gonna be good !

Check out Jeff Stocker’s “We Fought Desperate” for the best account of the 153rd PA.

Jon Tracey brings needed perspective to understand the events of July 1 afternoon. In a recent comment, I cited an article by Matt Atkinson in the Gettysburg Seminar Papers about the role of Dole’s Brigade(from Rode’s Division) in the attack from the northwest on Blocher’s Knoll while Gordon was attacking from the north east. Von Gilsa and Ames were being asked to do too much. Dole’s Georgia Brigade faced numerous challenges from Union regiments before they eventually prevailed. It was “no cake walk” as a result of the stiff opposition of the Union forces in this area north of town.

Thanks! It was a tough fight for sure.

very impressed with this site. Please add me to the list. thanks

There’s a new marker on Barlow’s Knoll titled “Driven Back.” I assumed I had already photographed it, so I didn’t take a picture of it, and I can’t find anyone else with a photo of it.

Cameron,

Turns out I had a picture of it! I added it to the article for the enjoyment of you and other readers.

I appreciate the article. My great great grandfather served with the 25th Ohio which was on Barlow’s knoll in the vicinity of Wilkeson’s battery. His story in and of itself is tragic. The 25th served nobly and certainly was a fighting regiment.

I have visited the site several times. It is fairly obscure and not the easiest to find unless you are looking for it specifically. It is certainly not one of the prominent or popular places on the battlefield and is more often than not overlooked. Yet it is important to the unfolding of events of July 1.

Barlow is a fascinating study. Mr Welch’s book is a value resource to my own pursuit to write another biography on Barlow’s life with

much more focus on his post war career.

Andrea, I have also searched in vain for post CW photos of Barlow except for one taken during

The early 1870’s. I suspect searching through the Boss Tweed prosecution might yield

Some interesting information.