Under Fire: “Death waited often at our door”

When the invitation was given to contribute to this series on “First Experiences Under Fire” my thoughts, of course, drifted to the young soldiers with dreams of glory in combat, only to find that the battlefield wasn’t as glamorous as the recruiters had advertised. The ECW team will, no doubt, be sharing some incredible stories about these men. I, however, will be taking a slight detour. I want to leave the soldier narratives to others and focus on another group that came under their own kind of baptism of fire. When the men have suffered their first – or perhaps second or third – combat wounds, it’s time for the nurses and doctors to go to battle.

Society in the nineteenth century was divided into two spheres, the public and the private – commonly referred to as domestic. This distinction in spheres separated the genders and dictated their role and responsibilities within the community. Those in the public sphere – usually the men – had a dominant voice in politics and were allowed more flexibility in their occupations. Women, on the other hand, were relegated to the domestic sphere, where their priorities concerned their homes and families. It was uncommon for women to have paying jobs, with the exception of teaching, housekeeping, or other jobs related to the domestic sphere – anything having to do with caretaking and nurturing. Women were also expected to exhibit virtues of gentility, tenderness, compassion, and submissiveness. Homes were to be havens of peace for the family, maintained by the mothers and wives. Women who did not adhere to this unspoken social code were considered immoral and degenerate. There are, as with anything, exceptions to the rules, but this was the generally accepted role for women by the time of the Civil War.[1]

Society in the nineteenth century was divided into two spheres, the public and the private – commonly referred to as domestic. This distinction in spheres separated the genders and dictated their role and responsibilities within the community. Those in the public sphere – usually the men – had a dominant voice in politics and were allowed more flexibility in their occupations. Women, on the other hand, were relegated to the domestic sphere, where their priorities concerned their homes and families. It was uncommon for women to have paying jobs, with the exception of teaching, housekeeping, or other jobs related to the domestic sphere – anything having to do with caretaking and nurturing. Women were also expected to exhibit virtues of gentility, tenderness, compassion, and submissiveness. Homes were to be havens of peace for the family, maintained by the mothers and wives. Women who did not adhere to this unspoken social code were considered immoral and degenerate. There are, as with anything, exceptions to the rules, but this was the generally accepted role for women by the time of the Civil War.[1]

When the war broke out, women were inspired to do their part. Some disguised themselves as men and enlisted to physically fight for their respective causes, but the majority would do their best to contribute while still operating within the roles that jived with the domestic sphere. These included fundraising or gathering donations to send to the men at the front. Others would be inspired to take it a step further and “let our hands be those to cheer and minister to the sick and wounded who need our care.”[2] The field of nursing was not well established by the beginning of the war, and the job was often relegated to convalescing soldiers to tend after their comrades. To many, nursing was not a woman’s profession. The direct contact with men was considered morally compromising. Others thought that women, given their fragility, were incapable of hard work in a hospital setting. Their feminine sensitivities would inhibit them from knuckling down to the task of dressing wounds or cleaning up the wide gamut of bodily fluids that flowed in a hospital ward. Women proved the naysayers wrong and many thrived in the intense environment, driven by the strong conviction that they were serving their country by sacrificing their time and energy to help the sick and wounded. The emergence of women nurses would cause many to rethink the accepted standards of society in the decades following 1865.

At first, nurses were given tasks related to the domestic lifestyle, such as food preparation, writing letters for soldiers in their care, house cleaning, and some tasks generally associated with the nursing practice in modern times. African American women – born free or newly emancipated – and the poor were given more laborious jobs, such as cleaning the floors and laundering. Many even scorned being paid, as most women saw their wage-less status as a sign of moral and humanitarian dedication. One nurse wrote, “I learned to appreciate the noble-heartedness of the untiring nurse whose duties were for humanity’s sake, not surely for the 12 dollars a month, and soldier’s rations.”[3]

Work in the hospitals was hard and taxing. Like the soldiers, women who decided to “enlist” as Louise May Alcott romanticizes in her writings, came to realize just how difficult and tragic war could be. Many arrived to their positions in the hospitals with sick already present, but what were their first thoughts upon seeing the wounded flood through their doors, fresh from the battlefield?

In her work, Hospital Sketches, Louisa May Alcott tells the story of Tribulation Periwinkle, a fictional stand-in for her own short-term experience as a nurse in the Civil War. In her early chapters, Tribulation exhibited patriotic drive to serve the Union and become a nurse. Almost naively optimistic, she uses language to equate her actions with that of a soldier going off to battle. And similarly to the echoing sounds of distant cannon fire, Tribulation was called to action with the cry, “They’ve come! Hurry up, ladies – you’re wanted!” as forty ambulances were on their way.

Three days before their arrival, Tribulation had tended the sick, but she yearned for some greater work, saying “rheumatism wasn’t heroic.” She first witnessed the streets lined with the ambulance wagons and the gravity of her situation became realized as she “indulged in a most unpatriotic wish that I was safe at home again.” Inside the makeshift hospital, she was assailed by “a regiment of the vilest odors that ever assaulted the human nose.” So great was this assault that she carried a bottle of lavender water to combat the stench. When she came to the ward to assist one of the senior matrons, she finally saw the nurse’s equivalent of “the elephant.”[4] She observed:

“’our brave boys,’ as the papers justly called them, for cowards could hardly have been so riddled with shot and shell, so torn and shattered, nor have borne suffering for which we have no name, with an uncomplaining fortitude, which made one glad to cherish each as a brother. In they came, some on stretches, some in men’s arms, some feebly staggering along propped on rude crutches, and one lay stark and still with covered face, as a comrade gave his name to be recorded before they carried him away to the dead house. All was hurry and confusion; the hall was full of these wrecks of humanity, for the most exhausted could not reach a bed till duly ticketed and registered; the walls were lined with rows of such as could sit, the floor covered with the more disabled, the steps and doorways filled with helpers and lookers on; the sound of many feet and voices made that unusually quiet hour as noisy as noon; and, in the midst of it all, the matron’s motherly face brought more comfort to many a poor soul, than the cordial draughts she administered, or the cheery words that welcomed all, making of the hospital a home.”[5]

Her narrative mirrors the experiences of thousands of nurses who served in hospitals, either in a city, in a camp, or acquired homes or barns near the battlefields. In the face of such gruesome sights as men legless, armless, or desperately wounded, Tribulation knew she was “there to work, not to wonder or weep” and resolutely “corked up my feelings” before rolling up her sleeves and diving into the work ahead.[6]

Another nurse who found purpose in the field of nursing – one cited many times on this blog – was Cornelia Hancock. This Quaker from New Jersey had been rejected from nursing by Dorothea Dix for her youth, then twenty-three. With the help of a relative, she arrived to the little town of Gettysburg on the evening of July 6th, 1863, just days after the battle had ended. Most of the town had been converted into a network of hospitals, and the very same evening she arrived, she was sent to a church where she “saw for the first time what war meant.” She gazed upon “Hundreds of desperately wounded men… stretched out on boards laid across the high-backed pews as closely as they could be packed together… these poor sufferers’ faces, white and drawn with pain, were almost on a level with my own. I seemed to stand breast-high in a sea of anguish.” That first night, she spent going from board to board, penning letters to loved-ones for the men who could not write themselves. Some of these letters would contain the last words their soldier would ever impart to them.[7] Over the months and years she spent in nursing the wounded, she would claim “I feel assured I shall never feel horrified at anything that may happen to me hereafter.”[8]

Another account comes from Hannah Ropes, serving at a hospital in Washington, who wrote to her daughter about the events of July 5, 1862 – during the Peninsula Campaign. Hannah and the other nurses had been warned about the coming of the wounded and waited impatiently for their arrival. When they were finally called up, Hannah was met with a sight “as I hope you will never witness.” In the entrance hall “there bent, clung, and stood, in dumb silence, fifty soldiers, grim, dirty, muddy, and wounded.” Each were ushered to large rooms for care where “Everything they had on was stripped off – and, weak, helpless as babes, they sank upon us to care for them. With broken arms and wounded feet, thighs, and fingers, it was no easy job to do gently.” They were cleaned and their names taken for the records.[9]

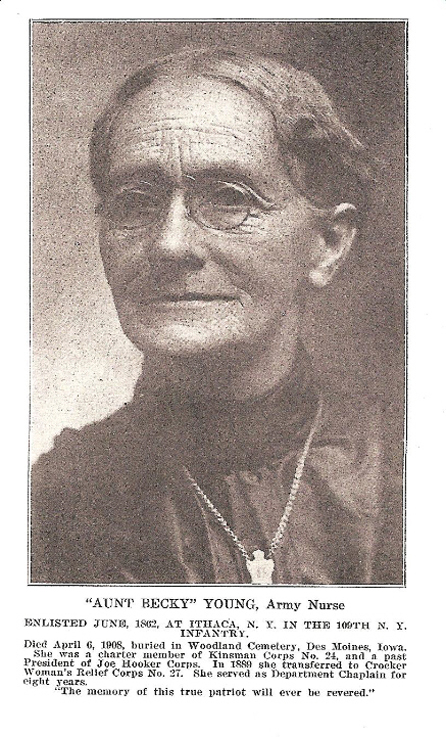

Sarah Palmer, another Union nurse, was of the brave opinion that nursing “was a place for women” and was glad to endure the “sneers of those who loved their ease better than their country’s heroes.” Sarah took her role as a nurse seriously, believing with such determination that “had there been more women to help us, many a brave man, whose bones moulder beneath the green turf of the South, would have returned to bless the loved ones left in the dear old home behind him.” Her narrative is fraught with the common patriotic sentiments of women at the time who knew that “if they[the soldiers] could suffer so much, and die for their country, I could at least give some years of my poor life in the attempt to alleviate their sufferings.”[10]

Like many nurses, Sarah not only tended the sick and wounded, but began her work as a nurse by cleaning in the home that had been confiscated for use as a hospital. As she continued in her occupation, she would remark briefly in her book on the battles, but revealed little of her first brush with the wounded as the above nurses had done. In her remarkable memoir, she wrote, “Death waited often at our door” and how her heart hurt for the men in her care. “Dying men looked into my face beseechingly, and I could give them no hope. They called for wife, and mother, and child in the swift workings of delirium, but no wife, or mother, or child could stand by the death-bed, to hear, as I heard, the dying words.”[11] She would write, rather poignantly:

“The cruel war of the Rebellion taught many a strange, sad lesson to us all, it made tongues familiar with tales of starvation, and death in prisons, and wrought descriptions of wounds so horrible, that the heart and soul grew sick, remembering the comeliness of the young soldier, who, in his suit of blue, marched proudly away to the war, and now – Oh, the wreck of beauty and manliness is hard to dwell upon.”[12]

Her words echo the thoughts and feelings of countless nurses and doctors who saw firsthand the devastation that war could inflict upon a single body. Some of their names are lost to the ravages of time, others are well known such as Clara Barton, Susie King Taylor, Kate Cummings, Phoebe Pember, Esther Hill Hawks, Mary Ann “Mother” Bickerdyke, Elizabeth Blackwell, Georgiana and Jane Woolsey, and Sophronia Bucklin. They may have not taken up a rifle to fight the enemy, but they fought their own battle against death behind the scenes.

Endnotes

[1] Nina Silber, Daughters of the Union: Northern Women Fight the Civil War, Harvard University Press, 2005, pp. 4, 87-88

[2] New York Herald, April 30, 1861

[3] Elizabeth Leonard, Yankee Women: Gender Battles in the Civil War, New York, 1994, p. 29

[4] Louisa May Alcott, Hospital Sketches, New York, Dover Publications, Inc, 2006, p. 19-20

[5] Ibid, p. 21

[6] Ibid.

[7] Henrietta Stratton Jaquette, ed, Letters of a Civil War Nurse: Cornelia Hancock, 1863-1865, University of Nebraska Press, 1998, p. 4

[8] Ibid, p. 8

[9] John R. Brumgardt, ed, Civil War Nurse: The Diary and Letters of Hannah Ropes, Knoxville, The University of Tennessee Press, 1980, p. 53

[10] S.A. Palmer, The Story of Aunt Becky’s Army -Life, New York, John F. Trow & Co., 1865, p. 2-4

[11] Ibid., pp. 19, 23

[12] Ibid., p. 20

Another interesting piece. Keep them coming. We are proud of you.

Norman Vickers

Pensacola Cw Roundtable

Thank you! I hope to see you at a CWRT meeting soon! 🙂

Bravo! Bravo! Very well done with this one Sheritta. I’m glad Aunt Becky’s book has proven a useful acquisition.

I was blown away by Sarah’s excellent writing! I’m looking forward to reading more. I’ve only read through the first half-dozen chapters, but so far it’s been an incredible read. Thank you again!

We attempt to answer, What was the Civil War? Sheritta Bitikofer’s excellent piece declares, This too. Thank you.

That is one of the best compliments I have received. Thank you so much!

Even today, we always acknowledge that the feats and endurance of the medical corps equals that of the folks who are kicking in the doors. The medical folks suffer from PTSD as much or more than the rest of us. As I read those passages form long ago, I see the strains of something like PTSD.

Tom