Under Fire: Is Past Always Prologue?

For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid and ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened to break out and Pickett himself with his long oiled ringlets and his hat in one hand probably and his sword in the other looking up the hill waiting for Longstreet to give the word and it’s all in the balance, it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet, it not only hasn’t begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and those circumstances…

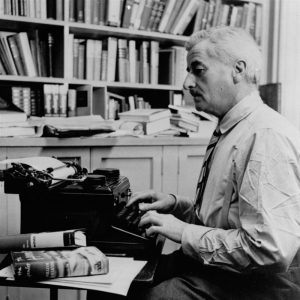

Some of the most famous words ever written about the Civil War–Gettysburg in particular–are conjured here by the great southern writer William Faulkner. In his 1948 novel, Intruder In the Dust, Faulkner wrote about the promise of the afternoon of July 3, 1863. His specific reference was the moment before the Confederate attack that became known as “Pickett’s Charge.” However, I think there is more that can be read into Faulkner’s words. Readers just need to play with them a bit.

Let us go back two years earlier, to July 21, 1861. Add Northern boys into Faulkner’s paragraph and fool around with the time a bit. Substitute Beauregard and Johnston for Pickett, then add Irvin McDowell in blue. None of these young soldiers have seen the elephant yet, not even those who would be members of the USCTs. Maybe one or two caught a glance of it at Blackburn’s Ford a couple of days earlier, but none of the volunteers who answered Lincoln’s call for “75,000 Men” had any idea what he would do in an actual battle. Would he be brave or cowardly? Might he get hurt or seriously hurt someone else? What about dying? Nobody had talked very much about that part. We will share with our readers some thoughts from ordinary soldiers and officers about exactly how they saw battle, especially the first one. No hardened vets here–the last war was over twenty years ago. The reputation of the family, the town, the state, and the world seemed to be resting on many sets of slim shoulders that day.

Lesley J. Gordon’s brilliant and sensitive book A Broken Regiment: The 16th Connecticut’s Civil War discusses how the repercussions that a whiff of cowardice could impugn an entire regiment. She also clarifies that there were many ways a regiment could get a reputation for fearfulness. That issue could become intermixed among soldiers, the war, and the history of that war. Ms. Gordon’s work combines her usual fine culling of resources with her unique ability to read the nuances of the letters of young men. She vetted this work by presenting it in chapbook form before sending it to her publisher, Louisiana State University.

Nevertheless, before that reputation is made and before historians start interpreting what happened–good or bad–let us remember that for all of them:

… it’s all in the balance, it hasn’t happened yet, it hasn’t even begun yet, it not only hasn’t begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin against that position and those circumstances… The past is not dead. It’s not even past.

“The reputation of the family, the town, the state, and the world seemed to be resting on many sets of slim shoulders that day.”

I think this says a lot about why so many Confederates joined up initially, then stayed through the end of the war. The Confederacy obviously had a recruiting problem, even in the early days of the war: it enacted its conscription law in early 1862.

Many Confederates may not have been rabid States Righters—but they did want to be seen as upstanding men in their communities. The fact that companies and batteries were often recruited from the same towns or counties must have intensified pressure to join up. In the early years of the war, going to war didn’t mean getting on a train to go to some far-off basic training site: it meant signing up and falling into ranks with your neighbors, in front of your whole community. Who could hope to be accepted in polite society back home after the war, if they’d been branded as shirkers by their neighbors?

My great-grandfather, a member of the 14th Virginia Cavalry, was a subsistence farmer after the war. He made ends meet by selling meat and produce to local businesses. If he’d been branded as a coward, I have no idea what he would have done.

As the war went on, soldiers may have lost faith in the Confederacy, but many stayed loyal to their units, and their comrades in those units.

Excellent comments–soldiers were pretty upset halfway through the war when their home units were blended in to regular units–that identity with home and hearth is the defining difference between the militia and mercenaries.

Not to start any controversy over monuments again, but this is why I feel the local county courthouse monuments should be left alone. Those were the ones honoring and dedicated to the fathers, sons, brothers, husbands, and neighbors who accepted that call to fight. I feel like the communities truly wanted to honor and remember those men, instead of the racial overtones everyone seems to think of nowadays, but that’s just my humble opinion.