A Close Brush With History—UWF History Trust’s Black Politicians Exhibit

It was recently announced in the last Emerging Civil War newsletter that I’ve taken on a part-time position with the University of West Florida’s Historic Trust in Pensacola, Florida. I had begun volunteering in their Collections Department – and diversifying in their archives occasionally – since the beginning of June of this year. My first day began with a bang – or lack thereof – when the bomb squad had to be called regarding a potentially live Civil War cannonball found in the collections building. It was not live, and it was properly disposed of, but I found it all thrilling! I volunteered twice a week and each day I couldn’t help but marvel, “They’re actually letting me do this! This is so cool!” I’ve processed items like an 1812 daybook complete with drygood store purchase ledgers, mortgage deeds from the 1920s, clothing and toys from the last two centuries, paintings, photographs, and even some things we would consider “modern” like a 21st century Nokia phone. No day was ever dull, no item ever too insignificant to me. When a paid position opened up, I jumped on it.

What I hadn’t expected was to come into contact with some darker spots of local and national history. A new exhibit recently opened at the Pensacola History Museum entitled “2000 Men: Black Politicians During Reconstruction.” I was ecstatic! This was a period of time closer to my field of study, and I, along with a few other volunteers, worked to get the exhibit ready for the big opening. This involved pulling objects and artifacts from storage for public display. Some were fairly basic, such as letters and archival material, some political campaign buttons, and a couple of ballot boxes for the “voting center” display. Something that I didn’t think about, which I probably should have in hindsight, was the involvement of the Ku Klux Klan in the Reconstruction Era and that organization’s influence on local politics.

Pensacola, like many cities in the South, had its fair share of turbulence and racial violence after the war and well into the twentieth century. Its attitude toward black equality and equal rights were not unusual for the age, but that does not condone its existence. There were efforts to sweep this part of the city’s history under the rug, tucked away in a back corner to be forgotten and ignored. It’s never a topic the public wants to be reminded of, though it should be. So, doing their due diligence in representing the history of black politicians in Pensacola, there is a display detailing the emergence of racial hate groups. This meant pulling out a KKK uniform from collections, along with a cross that was used during their processions.

That day, all the collections manager said was, “We’re going to go over to the exhibit and dress a mannequin.” I thought she meant dressing a mannequin to represent a black politician. It didn’t take long for me to realize I was wrong. I saw the KKK uniform, folded in a neat white pile on a nearby table, partially wrapped in tissue from its previous life in storage.

Looking at it, as I would look through exhibit glass, I recognized what it was, and it didn’t phase me too greatly. I had seen these uniforms in many museums and had become somewhat desensitized to it – for better or worse. But when I picked up the robe in order to dress the mannequin, the feelings erupted. I thought, “Whose hands had touched this nearly a hundred or more years ago? Who actually sewed this together, knowing what it would be used for? What rallies had this uniform been through? Did the man who wore it commit acts of hatred and violence?” My hands started to shake a little and I had to distance myself from what I was doing. Still, the intense feelings didn’t subside. I had touched a piece of history that I never thought I would have to.

Just a few weeks prior, I had processed two “Mammy Dolls,” little porcelain baby dolls with black faces and stuffed bodies. I began to wonder about the little girl who could have owned that doll, and if she had ever seen a man wearing a long white robe and pointy hat. Did she see a pair of glaring eyes behind the fabric mask, filled with unbridled hate for her and her family, simply for the color of her skin?

I haven’t been with the UWF Historic Trust for long, but what I have experienced thus far has made me look at history with a new perspective. Everything is connected and every artifact tells a story.

For those who are in the Pensacola area, I highly recommend you visit the museum and tour through this exhibit for yourself. Here is a brief explanation of their new exhibit:

2000 Men: Black Politicians During Reconstruction

Opens to the public: October 8, 2021

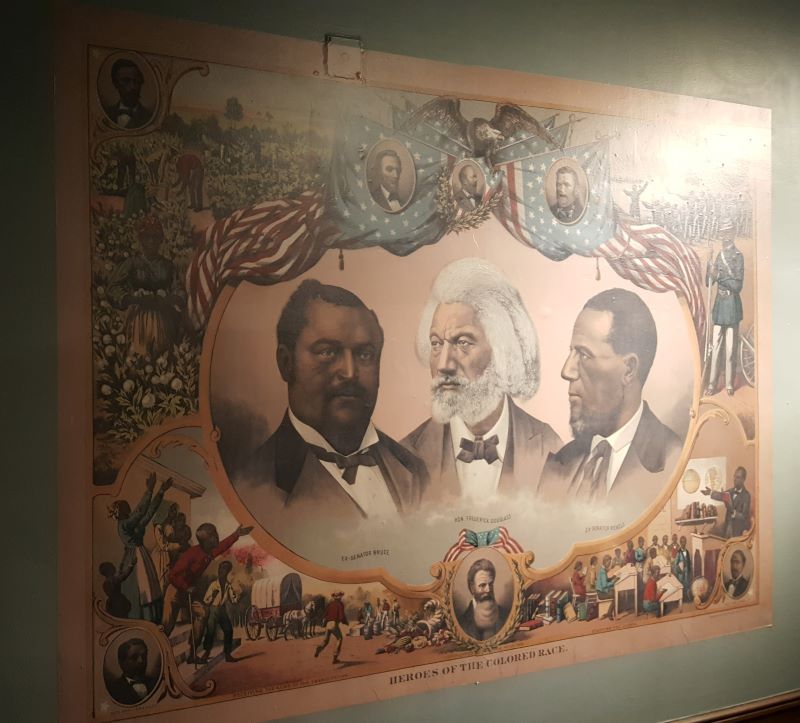

Coming to the Pensacola Museum of History is 2000 Men: Black Politicians During Reconstruction. After the Civil War, newly enfranchised Black men entered the world of politics for the first time. The inclusion of African Americans as not only citizens, but as voting constituents greatly impacted politics in the United States. Impacts from this crucial time in American history are still seen today. Though the exhibit highlights local Black politicians, items on display will enhance the story of overall understanding of the national context. Portraits, letters, and memorabilia will soon fill the third floor of the museum! Be sure to come visit during the fall to be among the first to view 2000 Men. The exhibits team is always looking for items to help tell our story. If you, or someone you know, may be interested in donating items relating to this or any of our exhibits, please reach out!

Nice post. We must never forget or erase the past, but learn from it! Thanks Sheritta.