Civil War Cooking: Sam Watkin’s Farm House Dinner

In the autumn of 1863, Private Sam Watkin in Company “Aytch” of the 1st Tennessee Infantry Regiment got sent on a foraging mission into the countryside of Georgia to bring back food. Somewhere along the way, he got a memorable dinner…in more ways than one:

For several days the wagon train continued on until we had arrived at the part of country to which we had been directed. Whether they bought or pressed the corn, I know not, but the old gentleman invited us all to take supper with him. If I had ever eaten a better supper than that I have forgotten it. They had biscuit for supper. What! Flour bread? Did my eyes deceive me? Well, there were biscuit – sure enough flour bread – and sugar and coffee – genuine Rio – none of your rye or potato coffee, and butter – regular butter – and ham and eggs, and turnip greens, and potatoes, and fried chicken, and nice clean plates – none of your tin affairs – and a snow-white table-cloth and napkins, and white-handled knives and silver forks. At the head of the table was the madam, having on a pair of golden spectacles, and at the foot the old gentleman. He said grace. And to cap the climax, two handsome daughters. I know that I had never seen two more beautiful ladies. They had on little white aprons, trimmed with jaconet edging, and collars as clean and white as snow. They looked good enough to eat, and I think at that time I would have given ten years of my life to have kissed one of them. We were invited to help ourselves. Our plates were soon filled with the tempting food and our tumblers with California beer. We would have liked it better had it been twice as strong, but what it lacked in strength we made up in quantity. The old lady said, “Daughter, hand the gentleman the butter.” It was the first thing that I had refused, and the reason that I did so was because my plate was full already. Now, there is nothing that will offend a lady so quick as to refuse to take butter when handed to you. If you should say, “No, madam, I never eat butter,” it is a direct insult to the lady of the house. Better, far better, for you to have remained at home that day. If you don’t eat butter, it is an insult; if you eat too much, she will make your ears burn after you have left. It is a regulator of society; it is a civilizer; it is a luxury and a delicacy that must be touched and handled with care and courtesy on all occasions. Should you desire to get on the good side of a lady, just give a broad, sweeping, slathering compliment to her butter. It beats kissing the dirty-faced baby; it beats anything. Too much praise cannot be bestowed upon the butter, be it good, bad, or indifferent to your notions of things, but to her, her butter is always good, superior, excellent. I did not know this characteristic of the human female at the time, or I would have taken a delicate slice of the butter. Here is a sample of the colloquy that followed:

“Mister, have some butter?”

“Not any at present, thank you, madam.”

“Well, I insist upon it; our butter is nice.”

“O, I know it’s nice, but my plate is full, thank you.”

“Well, take some anyhow.”

One of the girls spoke up and said: “Mother, the gentleman don’t wish butter.”

“Well, I want him to know that our butter is clean, anyhow.”

“Well, ma’am, if you insist upon it, there is nothing that I love so well as warm biscuit and butter. I’ll thank you for the butter.”

I dive in. I go in a little too heavy. The old lady hints in a delicate way that they sold butter. I dive in heavier. That cake of butter was melting like snow in a red hot furnace. The old lady says, “We sell butter to the soldiers at a might good price.”

I dive in afresh. She says, “I get a dollar a pound for that butter,” and I remark with a good deal of nonchalance, “Well, madam, it is worth it,” and dive in again. I did not marry one of the girls. [pages 83-85]

And one autumn afternoon in 2021, I set out to recreate this farmhouse dinner. One of the fun things about experimenting with historic cooking is occasionally recreating a full menu to see how the flavors go together. I knew just by reading that this would be a good one.

Let’s start with the butter! As the un-name old lady points out in her verbal spat about the butter, the creation of this dairy product could provide notable extra income for a farm or household. Selling butter or eggs, often the domain of the womenfolk, to the local store or to wealthier residents could easily make that extra money for a new bonnet or perhaps cover to the difference if the crops weren’t as good. Fresh cream would be churned or rocked until butter formed and the buttermilk separated. Then the buttermaker would strain the butter from the liquid, press it, mold it, and pack it so that it would stay fresh. Although I had sticks of butter in my modern refrigerator, it just didn’t seem right to use them for this meal where butter was such a point of controversy. Lacking a historic churn and not having enough friends to do the elementary school “shake and pass the jar method,” I whipped cream with my electric mixer until the butter formed. Then I pressed and shaped it into a smooth ball and set it aside to meet its delicious fate with warm biscuits later.

While first reading Watkin’s story, I couldn’t decide if he was talking about yeast bread AND biscuits or just biscuits made with good flour. Perhaps I took the short-cut, but I decided to just make biscuits. The soda biscuit recipe in William C. Davis’s book “A Taste of War” was pretty easy to follow and made surprising light treats after kneading for 15 minutes!

Full disclosure, I did not make homemade fried chicken this time and I used the ham I had on-hand which wasn’t a large slice.

So, what is the “California Beer” that Sam writes about? After doing a little research, I think it might have been what is now called “Steam Beer.” Getting its name from the invention during the California Gold Rush, it’s brewed with lager yeast and without a chilling process. Eventually, the technique made its way to the James River Steam Brewery Cellars near Richmond in the post-Civil War years. (For the beer connoisseurs reading this post, it seems that this Richmond brewery was started by David Yuengling, Jr., the son of the famous beer crafter in Pennsylvania.) As for Sam Watkins’s story, perhaps “California Beer” was being crafted domestically or in small-scale commercial production; interestingly, he clearly identified what type of beer it was and seemed familiar with it, suggesting that the drink had moved from east to west coast in about 10 years. For the food photo shoot, I did pour a light beer from some I had in the pantry for other cooking projects.

The turnip greens? It seems that one authentic way to cook them is boiling them in water with a splash of vinegar and some salt and pepper. They weren’t my favorite thing on the menu, but it was interesting to try a new vegetable.

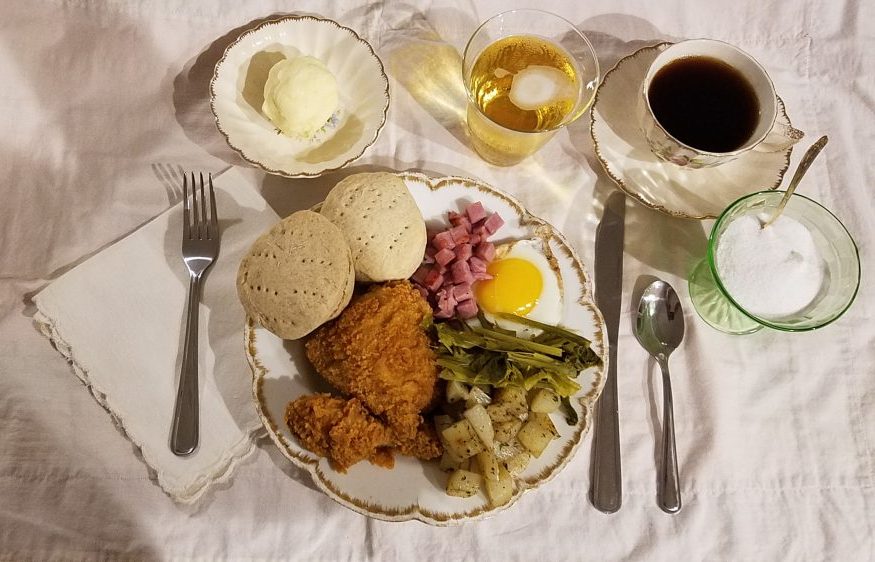

And here is the recreation of the feast, real 19th Century dishes included!

Great story! And your meal looks wonderful!

Only our Sarah would do this. I am thankful for her in so many ways.

Excellent story about a topic dear to every soldier every day & powerfully reinforced by replicating the meal. Well done!

Looks great. But, just one quibble, we will never know what sort of biscuits were they? Fluffy in the middle with a crust? The chewy kind? Flaky perhaps? Alas, Sam did not provide sufficient detail for a critical item in that wonderful meal…….

Tom

A true hands-on historian !

The California beer threw me for a loop. Great explanation Sarah!

A toast to this article’s host! To its father, mother and daughters, to the book and article’s authors. She wrote no culinary boast from the west or east coast, but a perfect compliment of the day from one of the historical ranks living. So to all a wish for a happy Thanksgiving.

A little late to the party here but I think you’d have liked the turnip greens a bit better had you cooked them with ham hock for flavor.