The Contested Origins of Gettysburg’s Virginia Monument

The Virginia Monument, one of the earliest and largest Confederate monuments on the Gettysburg battlefield, has a dramatic history. Ever since it was in the earliest phases of proposal, the monument has been a strong symbolic figure and elicited strong emotions. But what, exactly, does it symbolize? From its inception to its dedication to more modern periods, it has meant vastly different things to different groups. To Northerners, the inclusion of Southern monuments appeared to be a compromise to promote unity. However, as evidenced in initial debates about what the monument would portray, dedication speeches, and rededication, Southerners saw the monument not as a symbol of unity but rather as a way to reassert their separate identity.

In the early 1900s, many people began to debate the idea of placing Confederate monuments at Gettysburg. In 1903, an article entitled “Memorial to Lee” appeared in the Gettysburg Compiler. Thomas Cooper introduced a bill to the Pennsylvania legislature requesting $20,000 dollars for a monument of Robert E. Lee, provided that Virginia match that sum. Union veterans, such as the men of the Henry I. Zinn post of the Grand Army of the Republic opposed the monument, writing that they “could not, would not, and will not give its consent to place a monument at the expense of the State of Pennsylvania, at Gettysburg nor elsewhere in the State of Pennsylvania to his memory, being a rebel and a traitor whose shoulders were crimsoned and stained with the blood of thousands who gave their loyal lives in support of the flag.”[1] Although this bill certainly faced criticism, the Compiler’s article explains some of the background desire for Confederate presence in stone. “A ride along Confederate avenue, with the Union lines with their hundreds of markers in sight, gives a striking expression of the absence of all confederates(SIC) memorials,” the article states.[2] It then asks “Are the men who fought here still unforgiven rebels, who must remain unnamed as a punishment? Have we taken back their country as part of an indissoluble union but have not taken back the men?”[3] Although this bill failed due to opposition by Union veterans, it shows that even Northern citizens were beginning to feel a desire for Confederate memorials. Northern people saw those monuments as a proof of reconciliation, but Southern citizens had a different idea.

In 1908, Virginia began to toy with the idea of a state monument. In a speech to the General Assembly, Governor Claude Swanson made a case for it, stating:

A more glorious exhibition of disciplined valor has never been witnessed than that shown by the Virginia troops at the Battle of Gettysburg. The heroic achievements of our troops in that fierce battle have given to this Commonwealth a fame that is immortal, a lustre that is imperishable. I recommend that an appropriation be made to erect on this battlefield a suitable monument to commemorate the glory and heroism of the Virginia troops.[4]

Thus, the wheels began to move in earnest for the preparation for a monument to Virginia. One week after this speech, bills were proposed in both the House of Delegates and the Senate. These bills appropriated up to fifty thousand dollars and formed a committee, which would be composed of the Governor and four men who ended up all being Confederate veterans, to select “a location, design, and inscription for said monument.”[5]

There was not a unified national memory of the Virginia and Lee Monument before it started. As shown in the Gettysburg Compiler and the rules of the Gettysburg National Military Park Commission, which required neutral inscriptions, the Virginia Monument was to serve a purpose of unification. It was to show that although they had fought against each other they were now friends, and Confederate monuments would “be emblematic of a reunited nation” and would “show the same generosity which inspired Gen. Grant at Appomattox.”[6] To Southerners, however, it meant something radically different. To them, the monument was not a reminded of unity, but rather a reminder of separation and the glory of their cause and soldiers. The mention of the “heroic achievements of our troops” that earned “a fame that is immortal” are likely not the words of a group of people acknowledging defeat and reunion.[7]

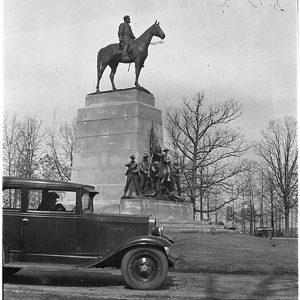

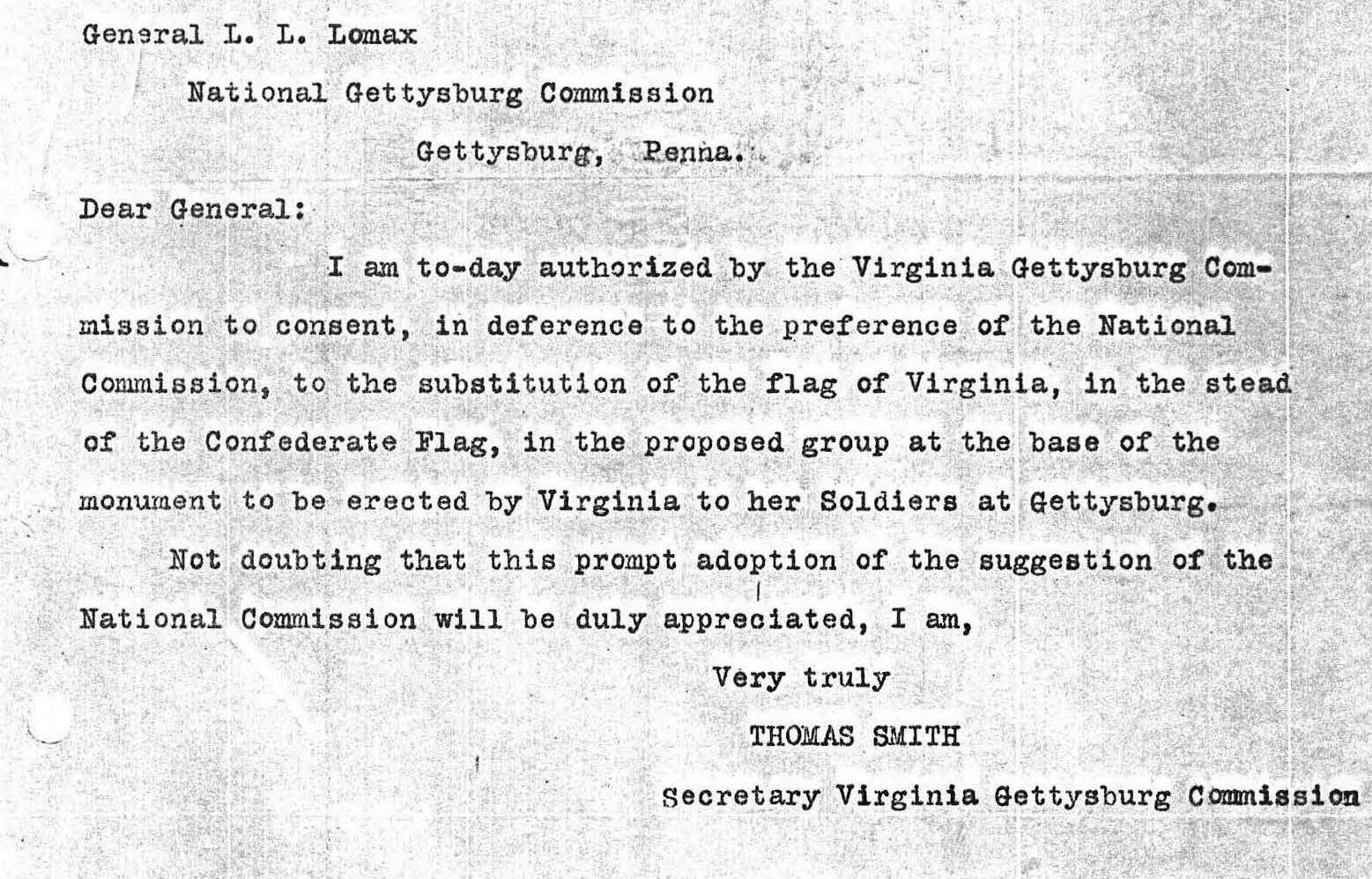

Nearly immediately after a state commission was appointed, differing ideas of the monument came to conflict. According to one source, the first location the committee suggested was at the Angle on Cemetery Ridge, the culmination of Pickett’s Charge. The government quickly refused that selection, and instead a location near Spangler’s Woods that faces towards Cemetery Ridge was chosen, allegedly the spot where Lee had met the survivors of the failed charge.[8] This was likely the easiest resolved issue. In July 1910, an issue developed with the proposed design of the statues of Confederate soldiers that were to be placed along the base of the pedestal. Initially, the soldier carrying the flag was to hold a Confederate battle flag. This was not approved, and the committee ultimately assented to replacing the Confederate flag with the Virginia state flag.[9] This was chosen as better representing Virginia, as it was a state monument, but the initial flag choice and denial likely had other political meaning. Perhaps the committee had chosen the more generic flag so that the monument could serve as a more universal Confederate monument, and perhaps the Commission had vetoed it because they did not want the battle flag flying as if it was victorious.

The final controversy was the one that was the most difficult to solve. In 1912, Virginia submitted the inscription for the monument, reading:

VIRGINIA

TO HER SOLDIERS AT GETTYSBURG

THEY FOUGHT FOR THE FAITH

OF THEIR FATHERS

John Nicholson, Chairman of the Gettysburg National Military Park Commission, refused to accept that inscription. The regulations pertaining to monuments demanded that inscriptions be without “censure, praise or blame,” and he believed that stating “they fought for the faith of their fathers” opened the inscription to “not a little adverse criticism” and “weakens the Memorial tribute.”[10] Instead, he proposed two potential options for the inscription:

V I R G I N I A

TO HER SOLDIERS WHO FOUGHT AT GETTYSBURG

V I R G I N I A

TO HER SONS WHO FOUGHT AT GETTYSBURG

Nicholson believed that the new inscriptions would “appeal to every soldier.” He repeated that there is no use “opening the doors of criticism” and stated, “let us… agree to a fact and not to an opinion.”[11] L.L. Lomax, a former Confederate general, quickly responded, agreeing that there was no need for the line “fought for the faith of their fathers,” though he also stated he needed to confer with another committee member, Thomas Smith.[12] Smith was clearly not in agreement with Lomax, as on March 29, 1912, he submitted the inscription again, still including the offending line, though he also wrote that he hoped “they are not in the least infringement in any way of the Regulations of the War Department.”[13] Nicholson was furious. He repeated that the inscription was not in accordance with the guidelines and continued a frustration filled correspondence with Lomax hoping he would reign in Smith. [14] This frustration was compounded by the fact that Nicholson needed Smith’s signature, and although Smith claimed that he had sent it, Nicholson never received it. Nicholson wrote that he had no confidence whatsoever in Smith’s memory and reiterated that “the Virginia Commission are making a great mistake in insisting upon an expression of opinion upon their memorial.”[15] Thomas wrote that he believed he had received approval for the inscription, to which Nicholson immediately replied that Thomas had received approval for the design and location, not the inscription.[16] Finally, Smith assented, and the final inscription was agreed to be “VIRGINIA TO HER SONS AT GETTYSBURG.”[17]

Following this lengthy correspondence, the construction of the monument continued. The base was placed in 1913, but the statues and inscriptions were not finished until several years later. On June 8th, 1917, the Virginia Monument was dedicated.[18] At the program, several speeches were given by various important individuals, and these dedication speeches further showed the split opinion on the memory of the war and purpose of the monument even further. First was the invocation, a prayer to begin the ceremony, given by Reverend James Powers Smith, who had been on Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s staff. As one might expect from a speech given by Smith, it was not one of reconciliation. He described the battle as “a great story of warlike power and skill, of unselfish devotion of life and every sacrifice to great ideals of rights and liberties.” The South still saw their war as a fight for personal liberty, ignoring the fact that it was fought as a war to prevent giving liberty to others.[19] Moreover, he described the monument as one dedicated to “the memory of an army of patriot soldiers and their great Captain.”[20] This was certainly not a prayer to call for unity, but rather one that called for the remembrance of brave southern soldiers who had simply fought for a just cause, ignoring the fact that he had called soldiers who fought against their own nation’s government “patriots” as well as ignoring slavery as the underlying reason for the conflict.

The official dedication, given by Henry Carter Stuart the Governor of Virginia, was no more willing to speak about unity than Smith was. Although he admitted the South had lost and the nation was politically reunited, saying that “destiny decreed that one unbroken republic under one flag should reach from Canada to the Rio Grande,” he still asserted a separate Southern social identity.[21] He stated the war’s cause was “divergent views of the Constitution of the United States,” and called it “a battle between rival conceptions of sovereignty rather than one between a sovereign and its acknowledged citizens.”[22] Through this, he thinly admitted the defeat, but also firmly asserted that the Confederacy had been a sovereign nation rather than a rebellion, and dismissed slavery as a cause of the war. Finally, he termed the monument an “undying expression of the high ideals in which we of the South would this day sanctify.”[23] The Virginia Monument was not dedicated as a symbol of a reunited United States of America; it was dedicated to permanently enshrine the Lost Cause ideals of virtue, heroism, and the righteousness of the Confederate cause. Rather than reuniting the nation, it firmly established the South as a separate social entity, even if the country was politically united. Even as the recent entry into the First World War brought Americans together, the Monument’s speeches drew a line between former foes.

In 1987, the Virginia Monument was rededicated by Mills Godwin, former Governor of Virginia. Rather than remedying the divisive, Lost Cause narrative of his predecessor in a post-Civil-Rights-Era age, Godwin doubled down. In his description of the battle there is no indication that the South lost the battle; there is no indication that the South lost the war and was now fully reintegrated into the nation. Instead he discussed how on July 1, Lee “crushed a Northern corps,” and how Pickett’s Charge was forced “to yield to superior strength,” harkening back to Lee’s General Orders No. 9 after Appomattox.[24] He states that Virginia was fully justified in “erecting a memorial to the valor and courage of her fighting men…and it was altogether appropriate that Robert E. Lee should be immortalized in bronze.”[25] Again, Southerners used the monuments to push their Lost Cause-inspired narrative of heroism and glory rather than as a symbol of unity.

Northerners had hoped that allowing Confederate memorials, such as the Virginia Monument, to be erected at Gettysburg would help bring the nation together through compromising and admiring the valor of their foes. Instead of reconciliation, the debates about flags, location, and description showed that Southerners were very reluctant to allow Northerners to push them towards a reconciliationist narrative. The dedication speeches and the rededication only show further that Southerners used this monument to push their own Lost Cause narrative, deifying Lee and his soldiers. Even in the face of the First World War, Southerners were not yet ready to fully reconcile with the North, instead preferring to use monuments to permanently enshrine their version of Civil War memory in bronze and granite. Rather than bringing the nation together, the first monument to a Confederate state at Gettysburg instead emphasized the divisions that still remained.

(Note: If you want to see some of these original documents for yourself, they’ve recently been digitized at https://www.nps.gov/gett/learn/historyculture/virginia-monument.htm)

[1] Undated Resolution of Henry I. Zinn Post, GAR, Mechanicsburg, Pa., copy in Harrisburg Civil War Round Table Collection, USAMHI, in Carol Reardon, Pickett’s Charge in History & Memory (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 114.

[2] “Memorial to Lee.” The Gettysburg Compiler. January 28, 1903.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Message of Hon. Claude A. Swanson Governor of Virginia to the General Assembly January 8, 1908, (Richmond: Davis Bottom, Superintendent of Public Printing, 1908), 10.

[5] Virginia’s Memorial to Her Sons at Gettysburg, (Richmond: The Colonial Press, undated), 3-4. Library, Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[6] “Memorial to Lee.” The Gettysburg Compiler. January 28, 1903.

[7] Message of Hon. Claude A. Swanson Governor of Virginia to the General Assembly January 8, 1908, (Richmond: Davis Bottom, Superintendent of Public Printing, 1908), 10.

[8] Short, James R. “Citizen Soldiers at Spangler’s Woods: A Sculptured Tribute to Virginia’s Sons at Gettysburg.” Virginia Cavalcade: History in Picture and Story Volume 5, Number 1 (Summer 1955): 45.

[9] Thomas Smith, letter to L.L. Lomax, July 31st, 1910. Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[10] John P. Nicholson, letter to L.L. Lomax, February 7, 1912. Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[11] Ibid,.

[12] L.L. Lomax, letter to John P. Nicholson, February 8, 1912. Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[13] Thomas Smith, letter to John P. Nicholson, March 29, 1912. Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[14] John P. Nicholson, letter to Thomas Smith, April 1, 1912. Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[15] John P. Nicholson, letter to L.L. Lomax, April 4, 1912. Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[16] John P. Nicholson, letter to Thomas Smith, April 6, 1912. Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[17] Thomas Smith, letter to John P. Nicholson, April 12, 1912. Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[18] Virginia’s Memorial to Her Sons at Gettysburg, (Richmond: The Colonial Press, undated), 1-2.

[19] “Address at the Dedication of the Virginia Memorial at Gettysburg, Friday, June 8, 1917 By His Excellency Henry Carter Stuart, Governor of Virginia,” civilwarhome.com http://www.civilwarhome.com/address1gettysburgvamemorial.html (accessed February 28, 2018), 1.

[20] Ibid.

[21] “Address at the Dedication of the Virginia Memorial at Gettysburg, Friday, June 8, 1917 By His Excellency Henry Carter Stuart, Governor of Virginia,” civilwarhome.com. http://www.civilwarhome.com/address1gettysburgvamemorial.html (accessed February 28, 2018)., 1.

[22] Ibid,.

[23] Ibid, 2.

[24] “Remarks by Mills E. Godwin, Jr., Former Governor of Virginia, Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, April 25, 1987, 3:00PM”, 2. Gettysburg National Military Park Library, Folder 17-67.

[25] Ibid, 3.

“The South still saw their war as a fight for personal liberty, ignoring the fact that it was fought as a war to prevent giving liberty to others.”

Well, it’s about time. I’ve come to expect that, once a quarter, an ECW contributor or guest blogger will write something that emphasizes the downsides of the Confederacy. (Of which there were many, I’ll stipulate).

Normally, when a publication runs an opinion piece on a controversial subject, you’d expect another contributor or guest blogger to respond and discuss the other side of the argument.

I no longer expect that on ECW. On this blog, it falls to those of us in the comments to mention those aspects of the Confederacy, and the men who fought for it and the women who supported it, that deserve to still be respected. (I think of that, every time I see ECW market a new book or ask us to buy tickets to an ECW event).

Many Southerners who fought for the Confederacy DID see it as a fight for personal liberty—including many Southerners who owned slaves. And, the Virginians who fought at Gettysburg—-again, many who didn’t own slaves—deserve to be honored for their heroism and determination.

And we will fight for our monuments. Because they honor our ancestors. My mother said that, when she saw the Jackson statue at VMI, she didn’t think of slavery or the Lost Cause. She thought of her grandfather, who was in the 14th Virginia Cavalry.

(We also just won a BIG victory in Virginia. The crew in Richmond that wanted to sanitize the state of monuments of anyone with ties to slavery just got beat.)

We’re not going away.

Donald,

Thanks for your thoughts.

I’ll also repeat a comment I often make. If you want ECW to have a certain type of content, you are always welcome to submit your own content for review.

Jon, if ECW’s front pagers are only going to write about the weaknesses of the Confederacy, and ignore or dismiss those aspects of it (and the people who fought for it) that still deserve to be respected today, then its coverage of the war, and its enduring legacy, will be one-sided.

I don’t know nearly enough about the Civil War to qualify as a front-pager, and I never will. But I’m sure there are quality historians who are willing to write respectfully and thoughtfully about Lee, Jackson, and those aspects of the Confederate cause that do deserve respect—the right to self-determination, standing up for one’s home, battlefield courage. It would be nice to see them, occasionally, on ECW’s front pages.

I’ll stipulate that ECW has allowed those of us who defend Confederate heritage free rein in the comments. No one from ECW has ever criticized me for supporting certain aspects of Confederate heritage. There are plenty of us “Lost Causers” here in the comments section.

Our policy at ECW is that writers here write about the things that are of interest to them, so we don’t assign topics or points of view.

I think it speaks volumes that of the folks here who write for ECW, all of whom have professional and/or academic training as historians, no one is interested in embracing any of the traditional Lost Cause ideology. In other words, the professionals know that a lot of the so-called Confederate perspective is a lot of hogwash.

That said, there are a few writers here who DO subscribe to a more southern-centric perspective of the war. Sadly, they don’t write about that because they have legitimate fears about repercussions in their day jobs. The problem they face is that as soon as they speak up on behalf of anything Southern, they’re immediately lumped in with the same people who spout nonsense like “The war wasn’t about slavery” and “Slavery wasn’t all that bad.” It’s hard to speak up on behalf of the South when too many Lost Causers make that terrain radioactive.

Jon relies in his post on primary sources. When I talk about slavery as the primary cause of the war, I point people to the primary sources. Yet I’m amazed at how pro-Southern advocates either refuse to acknowledge those primary sources or try to explain them away. Let’s start with those sources and THEN have a discussion. Perhaps it would be easier for everyone to then speak a common language without letting presentism interfere quite so much.

It would help to have a commonly-accepted definition of what the “Lost Cause” is, nowadays. Is any support of any aspect of Confederate heritage “Lost Causeism?” I certainly don’t consider myself a “Lost Causer”…but perhaps some people on ECW do. I’ll bet that many of us define the “Lost Cause” differently.

“The problem they face is that as soon as they speak up on behalf of anything Southern, they’re immediately lumped in with the same people who spout nonsense like ‘The war wasn’t about slavery’ and ‘Slavery wasn’t all that bad.’”

If people are unfairly lumping groups of people together, based on poor reasoning, then that speaks poorly of the people doing the lumping. If someone hears me say that there are some aspects of the Confederacy that still deserve respect, and instantly concludes that I didn’t think slavery was all that bad, I’d dismiss that person. If I heard some people say the Confederate cause was “glorious,” I’d dismiss them.

“It’s hard to speak up on behalf of the South when too many Lost Causers make that terrain radioactive.”

It’s hard to speak up on behalf of the South when too many “Lost Cause Police” will instantly label you as an apologist for slavery.

Having said all that, here’s the bottom line: “they don’t write about that because they have legitimate fears about repercussions in their day jobs.”

That’s good enough for me. NO ONE on ECW should be put in any kind of personal or professional difficulty, because of what they do or don’t write on this blog. I think that will limit ECW’s ability to be a comprehensive Civil War blog. There is a Confederate and a Union side to the Civil War. If a Civil War blog, or college Civil War history program, isn’t comfortable talking about the positives of the Confederate side, its coverage of the whole Civil War can’t help but tilt to one side.

But it’s not worth running the risk of anyone getting fired, or losing a promotion, 150+ years after the Civil War ended. We “Lost Causers” have plenty of opportunity to make our case in the comments. No one on ECW has censored me yet, and I’m confident no one will. For me, that will be good enough.

Donald

I would imagine your mother did not think of slavery when she saw the monument because she is a white women. Ask a black person what they think of when they see these monuments. Of course there were people who didn’t fight for slavery but the majority did-either to protect the institution or to protect their status in society (white men who didn’t own slaves but whose status depended on another group of people being lower than them). There is too much evidence that supports slavery being the root cause of war. Why does this bother you?

Thanks for the comment, Jessica. It’s important to consider that even those that did not enslave others often benefitted from the system, often through the practice of hiring out. Thanks for considering what others may see when they see monuments.

Jon Tracey You have left out the part about the large number of people in the North who benefited from slavery without directly enslaving others. Why is that? How about Northern banks that not only loaned to plantation owners but also owned plantations themeselves, through direct investment or bankruptcy acquisittions? The Federal Treasury collecting the bulk of its revenue from import tariffs on goods acquired largelt via sales of slave-grown cotton to Britain and France, etc., generating exchange credits as the largest US export until 1937, and 60% of total exports in 1860? Financiers, factors, and shipping interests that engaged in transport of cotton? Northern textile industrialists who purchased 20% of Southern grown cotton to make “dry goods” for domestic and export purposes? Or the many Northerners who under no circumstances welcomed an influx of African Americans to live in their States…..why are you not mentioning those?

Carson, because this article isn’t about that. But yes, northerners who supported enslavement of human beings were also bad and benefiting from a horrible system.

But, like I’ve said to others, if you’d like to write an article about that, ECW would take a look at it.

Jessica, you’re projecting quite a bit here, onto both me and the people who fought for the Confederacy.

Many soldiers fought for the Confederacy because they were conscripts, or feared being shunned by their communities. Many poor Southerners also feared economic competition from newly-freed slaves who’d presumably work for lower wages than they would. And, in some Deep Southern states, where blacks were a significant percentage of the population, whites feared being surrounded by people they viewed to be inferior—an opinion that most whites in the North AND South held of black people at the time. Let’s not forget that, in the Lincoln-Douglas debates, Stephen Douglas talked about blacks, Hispanics and “other inferior races.” Twenty years after the Civil War, William T. Sherman described Native Americans as “useless.” As a British author once said, “the past is a different country. They do things differently there.”

I never said that slavery wasn’t the root cause for the Civil War. But there were many causes. History is a complex subject, with many shades of grey, because people are complex.

Why are you insisting on a simplistic explanation for a complex subject?

I’ll stipulate that many of the Confederate statues that have come down in recent years did have undeniable social drawbacks. They were in prominent places in cities and towns that now have large (or majority) African-American populations. To many people, they symbolize backward thinking. (I’m confident the German companies that invest in modern-day South Carolina weren’t too happy about the Stars and Bars that flew next to the state capitol building for all those years). Times and people change. I’m a proud descendant of Confederate soldiers—and I can’t come up with a good reason for why Richmond and Charlottesville needed to keep their Confederate statues.

Battlefields, though, are for the most part destinations that people have to make an effort to visit. They are secluded places where it’s appropriate for people to reflect on the past, with all its complexities.

Evidence of the “root cause” of the war is not the same as the motive for serving in the Confederate military. This memorial recalls the individual soldier, not the Confederate government. This memorial addresses personal service, not the raison d’etre of the CSA. In his book, “For Cause and Comrade,” McPherson says most Southerners expressed a sense of patriotism as their motive for serving. 57% in fact. While a smaller number – 20% – did indeed espouse maintaining slavery as their motive for serving. The results for the Federal troops was similar – about 60% expressed a sense of patriotism as their motive for serving.

Tom

Tom, you raise some good perspectives, but remember that “patriotism” as a cause means supporting government and country–and the Confederate government was explicitly pro-slavery in its very conception.

Donald,

Regarding your note on front-pagers, I do honestly believe that if you look back you’ll find content that looks at those concepts thoughtfully.

You mentioned that battlefields “are secluded places where it’s appropriate for people to reflect on the past, with all its complexities,” and I’d agree with that. I also think that your most recent comment at 9:20 shows that you and I have a lot of common ground on the social drawbacks. You’ll also note that nowhere in my piece did I call for removal from the battlefield. This article is simply to highlight some really neat primary sources that are now digitally accessible and share some of those complexities for reflection.

Jon, thanks for your thoughtful reply. We’ll have to agree to disagree on the amount of respectful coverage of Confederate heritage on the ECW front pages, especially over the past 2-3 years. It’s my opinion that there’s a strong “Lost Cause Police” flavor to the ECW front page—but I’ll stipulate that others can and do see the matter completely differently. Regardless, y’all have always allowed me to have my say, and I appreciate that.

I’ll also stipulate that you did not call for removal from the battlefield—but others have, and seem very intent on trying to do just that. We also saw the Stonewall Jackson statue expelled from VMI, although only a small minority of activists were calling for that to happen.* Therefore, those of us who support Confederate heritage are being especially watchful.

* I admit that not all Stonewall Jackson statues are the same. Dr. Carolyn Janney, Civil War historian at the University of Virginia, notes that the Jackson statue in Charlottesville was erected in a majority-black neighborhood—presumably deliberately. And, from what I know, Jackson himself wasn’t a major figure in Charlottesville history. So, I can’t blame Charlottesville for moving that statue.

The ECW front page can be hard to gauge. It depends on what contributors decide to focus on, as well as what kind of posts are submitted as guest posts. We don’t tell people what or what not to write, aside from when we suggest folks write to fit within a series. Plus, I’ll admit that sometimes my attention is drawn more to things I disagree with rather than other things.

The VMI statue is an interesting story for sure – it’s being moved to New Market. (https://www.vmi.edu/news/headlines/2020-2021/vmi-begins-to-relocate-the-stonewall-jackson-statue.php) He wasn’t at New Market, of course, but it’s something worth following.

Don, you’re always thoughtful and respectful in your comments, and so we’ll never put a lid on you for that. You are an important contributor to the “marketplace of ideas” here, where conversation, discussion, and dialogue are essential. I appreciate your contributions, even if I don’t always agree with them.

Hi Jon,

As always you leave me with a wonderful sense of reflection after finishing one of your pieces. Thank you for writing what you do, and taking the time to find out the intentions behind less savory aspects of the Civil War. These discussions are not only important to have but crucial as the years go on. American identity and Public History can only benefit from thoughtful and well-researched scholarship as you displayed here.

Keep up the good work

Thank you, Francesca. All I wanted to do was take some primary sources out of the archival folder and present them for consideration.

It’s interesting that the South Carolina and Georgia memorials near the observation tower, dedicated in the 1960s, contain stronger “lost cause” language than the original proposal for the Virginia monument some 50 years earlier. In fact, George Wallace spoke at one of the memorial’s dedication, although I forget which one.

Thank you for an interesting article, although I think you were a little harsh on former governor Godwin.

Bill,

You’re correct, George Wallace spoke at the South Carolina dedication. If you’re interested in exploring the 1960s dedications more, Jill Ogline Titus has a few articles on them (https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1017&context=cwifac), as well as her new book (https://uncpress.org/book/9781469665344/gettysburg-1963/).

I also appreciate your thoughts on Godwin.

Jon-thank you for the link. I find this stuff fascinating. I was alive at the time the Georgia and South Carolina monuments were dedicated, although I was very young. There has obviously been quite an ebb and flow regarding Confederate monuments from the time of the Virginia monument to the 1960s and then to today.

Not to mention the Mississippi monument, which refers to its “brave sires who fought for their righteous cause” and depicts a Mississippian holding a flag-bearing Union soldier down with his foot whilst in the process of clubbing him to death with his rifle. Having read your piece on the park commission’s objections to Virginia’s monument in early 1900s, it amazes me that this monument was approved by the NPS in the early 1970s, smack in the midst of the fallout from federal Civil Rights legislation. This is not a monument to the spirit of reconciliation that motivated the creation of the five national battlefields during the so-called Golden Age of battlefield preservation.

The Mississippi State Monument, one of the most dramatic and interesting of the monuments on the battlefield, actually represents a member of William Barksdale’s Brigade fighting, while beneath him lies the Brigade’s color-bearer.

“The South still saw their war as a fight for personal liberty, ignoring the fact that it was fought as a war to prevent giving liberty to others.[19] ” It’s amazing that you have the power to read the minds of c. 5 million people with such authority! Articles like this are the epitome of divisiveness and part of the 155+ year old fight to justify the very unfortunate method chosen by the Union to resolve sectional differences, and are designed to continue exacerbating that division, intentionally. Despite all the evidence that has been shared for your benefit in this discussion, you are still completely ignoring anything that Southerners had to say then and since then. As always, if you refuse to acknowledge historic facts that disprove your stance, or to consider (or even learn about) the broader contexts of this history, you are doing no service to yourselves. The truth persists and will despite your best efforts to hide it. If Davis was fighting to preserve slavery, part of an entrenched economic system with significant participation by the North, why was he negotiating with foreign powers on the basis of emancipation in exchange for recognition, from Nov. ’61 on?

I think the division is evident in the primary sources I cited that were, indeed, written by people from the state of Virginia.

If you’d like to submit a post on Davis’s negotiations, the submission guidelines are here (https://emergingcivilwar.com/mission-statement/submission-guidelines/).

He doesn’t need to read the mind of c. 5 million people–he needs only look at the Confederate constitution or read Alexander Stephens’s Cornerstone Speech or look at the articles of secession for the southern states. Those primary sources all quite explicitly talk about slavery–the practice or refusing to give liberty to others–as an integral part of the Confederacy. That’s the starting point for any honest discussion.

Assuming anyone other than those who drafted those documents tossed a glance at Stephen’s speech or any of the articles of secession.

Tom

What about, and this is an honest question, all the personal accounts I have read that tie defending the South to resisting invasion? That resentment of invasion seems to have motivated volunteerism in the South more than anything else.

Huzzah to all who contributed above. Learning to play nicely in the sandbox is harder for some than for others. I suspect many readers would be surprised to learn the diversity of the backgrounds of our ECW “front pagers.” Long may we wrangle–then let’s have a cold cider!!

I have a different read on the addresses delivered at the monument’s dedication. First of all, I was struck that the event happened on Jan. 8, 1917, only months after the USA had entered WWI. Speaker N. 3, Sec. of State William M. Ingraham states that “the inspiration that this monument gives us” will help “us solve the difficulties of the present hour.”

Reverand James. H. Smith, formerly on the staff of Stonewall Jackson, voices the same concern for America “in this day of cloud and great concern.” He writes, “Many of us have come up from the far, broad fields of the South, and here we are met a great company of men from every section of the land- and now we stand under one flag, united again, and filled with a like spirit of patriotic brotherhood.”

Virginia Governor Henry Carter Stuart also expresses the sense of one country united in peril. He hopes that Virginia’s monument will serve “as a fresh and abiding inspiration to all men North and South who in this trying hour of our National existence would stand shoulder to shoulder in defense of our common country.”

Each of the above-mentioned speakers, and there were two others, felt strongly that North and South were united under one flag, united to face a common enemy in Europe.

Each speaker also lauded the heroism of Confederate soldiers who, in the words of Sec. Ingraham, fought and died “for a cause they sincerely believed was just and right.” At the close of his address, Ingraham praises Virginia’s beautiful statue and assures his listeners that “as long as bronze and granite endure, it shall stand as a loving tribute to those brave men.”

I hope that promise is kept.

Katy,

I certainly agree that the proximity to US entry to WWI makes it especially interesting. I note your quotations hint towards union, but still believe the tensions amidst the correspondence during the planning as well as statements of separate identity and “a battle between rival conceptions of sovereignty rather than one between a sovereign and its acknowledged citizens” complicate that idea.

I’d also again point out I made no calls for removal.

I didn’t see that you called for removal. I’m just afraid of it. Thank-you for introducing an interesting topic.

“The mention of the “heroic achievements of our troops” that earned “a fame that is immortal” are likely not the words of a group of people acknowledging defeat and reunion.” That is one interpretation of those words, not the only interpretation. The word “likely” should be replaced with the word “possibly.” The author is engaging in stereotypes.

It is the rare memorial that would describe those being remembered as “defeated,” “wrong,” or “selfish.”

Tom

I like Sec. Ingraham’s description of the Virginia monument as a loving tribute. We can all be sensitive to the South’s wish to memorialize the men that fought and fell.

“We can all be sensitive to the South’s wish to memorialize the men that fought and fell.”

True…we can be. In fact, we should all be sensitive to, or understanding of, that wish.

“The South still saw their war as a fight for personal liberty, ignoring the fact that it was fought as a war to prevent giving liberty to others.”

This is a significant over-statement. Why would a memorial be required to acknowledge the effect that war would have on slavery? Should all war memorials reflect the political reasons a given war was wrong? Should a Viet Nam War memorial acknowledge the US was engaged in a form of imperialism so as to oppose communism? Should an Iraq War memorial acknowledge that the weapons of mass destruction were never found? Should WW I memorials acknowledge that the smaller countries were carved up like turkeys in in the peace that followed?

Tom

Yes, I think war memorials should acknowledge the messier parts. In fact, with your example of the Vietnam Memorial, I think it indeed does that. It was designed as an “open wound” on the landscape. It doesn’t glorify the war, but instead remembers the immense personal loss it caused.

History is messy, and we do a disservice by forgetting that.

You speak of “the” Viet Nam memorial, overlooking dozens around the country remembering those who sacrificed in that war. Should they all mention the messier parts of the Viet Nam war? If so, they would not serve a memorial function any longer. I can see why “the” Viet Nam memorial in Washington might address political considerations. But, why would all the others scattered around the country memorialize US imperialism? I am a veteran of the Iraq war. Have attended a few memorials. None ever discussed the political aspects of the war. Why would they? The purpose of a “memorial” is to memorialize those who who fell.

Tom

“In reality no one in the South would have raised an arm to fight for slavery. It was an evil that we had inherited and that we wanted to get rid of”

– Moses Ezekiel, world-famous sculptor, and a VMI cadet who fought at New Market.

Life’s complicated, isn’t it?

https://www.baconsrebellion.com/wp/fact-checking-northams-vmi-speech/#disqus_thread

Donald, we had a lot of common ground in previous comments, but not here. I strongly disagree with Ezekiel’s assertion that chattel slavery was a “necessary evil” forced upon enslavers, and dislike that it brushes aside the fact that it was horrible for the millions of people who were enslaved.

Jon, I hope you’re not implying that I agree with Ezekiel that “chattel slavery was a ‘necessary evil,”’

Don’t take my last comment any further than the words I quoted and said. For those people who say that all Confederate soldiers, writ large, should be viewed as fighting for slavery, here’s one of those soldiers who wasn’t.

I’ll stipulate that Ezekiel, based on your quote of him above, apparently supported slavery, or at least didn’t mind it. My quote of him shows that (unless he was lying), he wasn’t willing to go to war to defend it. (Just as most Federals weren’t willing to go to war to abolish it. They called it the Union Army, not the Abolition Army.)

Jon-did Ezekiel say “evil” or “necessary evil”? There is no question that slavery was the principal underlying cause of the war and that many in the South wanted to preserve that institution. However, we all inherit the world that we are born into. Many in the South, including I believe Jefferson, saw the evil in slavery but did not know what the heck to do about it.

Ezekiel was wrong to say that no one in the South would defend the institution of slavery, but he is probably right to say that he and others in the South viewed slavery as evil. As others have commented in this post, the ordinary Confederate soldier believed that he was fighting for his community and family. That is a very strong human emotion.

One of the tragedies of the war was that fundamentally good people like Ezekiel were ultimately fighting for an evil institution. That does not negate their courage or their desire to protect their community and family. To quote the song “Ruby”, “I’m not the one who started that old crazy Asian war, but I was proud to go and do my patriotic chore.” How many American soldiers in Vietnam endorsed the domino theory of Communist containment? I’m not comparing the Vietnam War to defending slavery, but sometimes all we have are bad choices.

I have a lot of trouble with those, north or south, who historically paid lip service to slavery being bad but then brushed it aside by saying they didn’t know what to do about it. Jefferson benefitted immensely from the labor and skills of those he enslaved, and he pushed the issue off on the following generation. Inaction, or the lack of will to decide on action, simply perpetuated the horrors of slavery. They often directly, or indirectly, benefitted from it (again, north or south), so sometimes it comes off as “Well I do know it’s bad but it helped me so I don’t really want to deal with it and will turn a blind eye.” And there were those who saw it as evil and tried to do something about it, white or black.

Not sure what those who “historically paid lip service to slavery being bad but then brushed it aside by saying they didn’t know what to do about it” have to do with one war memorial for Confederate dead at the Gettysburg battlefield. You are conflating political issues – even if important political concerns – with one war memorial.

Tom

Other commenters shifted this particular thread to Jefferson and Ezekiel, so that’s the train of thought I was following.

Did Ezekiel say that it was a necessary evil or an evil that the South inherited? Isn’t it a “wolf by the ear” comment?

I don’t think that’s “complicated.” It’s Ezekiel, years later, trying to white-wash the slavery question.

I’m an Ezekiel fan. He created some beautiful art. So I’m not contesting his comment because I’m writing him off as a southerner. I’m saying he, like a lot of folks in the postwar era, tried to “explain away” the ugly.

“It’s Ezekiel, years later, trying to white-wash the slavery question.”

Or, it could be Ezekiel telling us why he chose to fight. What qualifies us, 150 years later, to determine what people really meant when they spoke on the record, 150 years ago?

Personally, I think we should presume that people mean what they say.

Once in a blue moon it seems, I am compelled to post the following “narrative” when discussions such as this one venture into subject matter like that of “Why they fought”. The aftermath of that fight is also fodder for such discussions. That said, I have presented the post below on this site a couple of times, and I will wager that I will do so again before I expire. As I always point out, I do not know who wrote it. I found it while browsing the Internet one day a few years ago, and I have no idea what site it was on. But to me, it is THE best summation on how attitudes and other things ‘evolved’ as to how participants in the War were honored, and other aspects pertaining what followed the War.

Full disclosure about this: I deleted a small passage that has reference to today’s partisan political climate and its affect on certain actions and events.I do not think that passage is necessary to this discussion. However, if anyone.wants the original post as I found it, feel free to message me. I’ll be glad to send it your way…

“The Rebel Flag…

On the rebel flag: I have always been a proud Yankee. “Union and Freedom Forever!”, so it’s like the Cowboys to an Eagles fan. You wouldn’t catch me dead flying that thing. But my southern friends don’t see it that way. Part of how we ended the Civic War, and the reason we didn’t have decades of guerilla war, was that we made an agreement with the South to RESPECT their heritage, even in defeat.

What was important, in this order, was we saved the Union and we freed the slaves. Lincoln wanted to free the slaves, but he knew that if we didn’t save the Union very bad things would have happened. History shows us what that might have looked like. So we damned Yankees agreed to give old Johnny Reb his due. We licked the Rebs, but we also knew that to preserve the Union and win them back to our cause, we couldn’t disrespect their honor and heritage. In turn, the Rebs became fierce patriots whose service to this country remains peerless. They more than atoned for the Civil War in their proceeding defense of our country since then.

Now some among us today want us to break our word. The progeny of Johnny Reb must now be made ashamed, they must be canceled. They must choose between their ancestors or this new version of a self-loathing America that is defined solely by her mistakes and failures, ignoring the fact our country is and was the greatest and freest country in human history! This is all too much.

For a second even I was tempted to fly Johnny Reb’s banner, as a token of respect to my southern friends. But I really can’t. To me it’s just a fallen flag from a vanquished foe of my country, but I totally see why to my southern friends it’s not that at all. It’s just a token of respect to their ancestors, many of whom, man for man, were just fighting for their home state.

I don’t agree at all with the Southern Cause, using states rights to justify slavery is morally reprehensible to me. But Johnny Reb wasn’t even attuned to any of those things, he just loved his state, back when that was still a thing, and it is still with me, I love Pennsylvania more than any other state in this Union and it is even more precious to me than America itself. I’ve studied the history of Germany in WW2 intensely. I can tell you, having poured over documents and letters from soldiers and their kin, even the German soldier in WW2, whose cause was even worse than any interpretation of the Southern Cause, was mostly just a young man serving his country. Few German soldiers saw much past the seeming necessity and mercilessness of the times to serve Germany.

The Southerner was mostly just serving his state. Most people have no such affection for their state, so they can’t grasp how Johnny Reb felt and why he fought. For these folks in grey and buttercup, their state called them and that was enough. Period. Just because you don’t get that doesn’t mean you can gainsay it.

So I won’t fly the flag of Johnny Reb, but neither will I join the cancel culture hysterics and their bid to open old wounds that could once again threaten our Union. As I said, my motto is “Union and Freedom Forever!” I will brook nothing that threatens our Union, not even if it means letting the South honor its ancestors and its heritage, though they hold no allure to me.”

Very well said. Thanks for sharing it, again.

To paraphrase Negan from ‘The Walking Dead ‘, “No one wants to see himself as the bad guy.” Why would any Confederate monument dedication acknowledge “we had slaves, we lost, we suck.” It was even stated in the article above that Northerners agreed to the Virginia monument, in part, to acknowledge the valor of their foes. But when the Southerners attempt to acknowledge their own valor, they are criticized for spreading Lost Cause myths, and not mentioning slavery or the fact that they lost. Any attempt to say anything positive about the Confederacy is quickly dismissed as Lost Cause garbage.

Why aren’t articles about Union subjects not required to acknowledge the 4 slave states still within the Union during the entire war, whereas EVERY article about the Confederacy has to say something about slavery? This is why those who appreciate aspects of Confederate history get so annoyed. We all know that the Confederacy lost and we all know that one of the most important causes of the war was slavery, but it does not need to be shoved down everyone’s throat in every article.

And, if this is the way scholarly works are written nowadays (the constant need to mention those “messy parts”), then why isn’t the same logic applied to WWII? Why are we not required to mention the atomic bombs and Japanese internment camps every time WWII is mentioned? Critics nowadays could pan both “Band of Brothers” and “Saving Private Ryan” for failing to mention the 2 atomic bombs we dropped on Japan or the Japanese internment camps back in the states. In fact, why should the citizens of the United States EVER have any pride or patriotism in our country, knowing that we put our own citizens in concentration camps and that we are the only country in the entire world to drop nuclear weapons on 2 civilian cities – they weren’t even military targets. But no one criticizes a Biden speech saying “oh, he failed to mention the bombs or the camps.”

Yes, history is complex and very messy, and I get that, but having to mention slavery and defeat in EVERY Confederate article seems a bit much.

“Any attempt to say anything positive about the Confederacy is quickly dismissed as Lost Cause garbage.”

I’d insert one of those thumbs-up emojis here, but I don’t see one, so I’ll go old school. 🙂

Just a clarification to Debra Page’s post, above:

“…to acknowledge the four slave states still within the Union…”

When I attended public school in Rock Island County, Illinois, I was indeed taught that Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Missouri were slave states that remained within the Union. But, this oversimplification missed: West Virginia, admitted as slave state in 1863; Indian Territory (today’s Oklahoma) where slavery was practiced by Native Americans; The Territory of Deseret (today’s Utah) where slavery “was hidden from Congress” and practiced into the 1860s…

My point: by seeking to condense History into “an accredited narrative,” the hard questions not only go unanswered; they go unrecognized.

Continue to demand answers to the questions of History. It is the only way we find the Truth.

Mike Maxwell

Here’s a few ECW articles on slavery in the United States:

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2018/12/21/the-abolition-of-debt-peonage-slavery-part-1/

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2018/07/10/beyond-the-13th-amendment-ending-slavery-in-the-indian-territory/

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/04/14/on-the-eve-of-war-the-missouri-bootheel/ Mentions pro-slavery Unionists there.

Here’s a few articles on Confederates that don’t discuss slavery:

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/08/17/fallen-leaders-general-richard-b-garnett/

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/06/29/braxton-braggs-beach-vacation-pensacola-in-the-early-months-of-the-civil-war/

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/06/23/flag-for-a-fallen-florida-colonel/

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/04/20/henry-adams-on-rooney-lee/ (technically includes the word slave in a quote but otherwise is not focused on it)

We also have articles that discuss how US officers were not paragons of virtue:

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2020/06/23/grangers-juneteenth-orders-and-the-limiting-of-freedom/

https://emergingcivilwar.com/2021/08/13/fallen-leaders-brigadier-general-nathaniel-lyon-part-ii/

Here’s a neat piece on how former Confederates that opposed segregation:https://emergingcivilwar.com/2017/02/28/confederate-generals-and-racial-moderation/

I’m sure with a longer search you’d find plenty more in these categories and others. Again, if you have a vision of what content ECW should be publishing, the submission page is wide open.

Thank you. I look forward to reading these. I want trying to call you out, per se, I was just noticing this trend in most Confederate articles whether the subject was directly related to slavery or not. It would be like the name “The White House” being permanently changed to “The White House That Was Built By Slave Labor”.

Otherwise, it was a nice article. I’d be interested to know how the imagery on the Mississippi monument got approved, since the regulations seemed tighter when the Virginia monument was getting approved.

We did some bad things in WW II. Nothing to be proud of. Our soldiers collected ears of dead Japanese. We did some torture. We killed some Japanese trying to surrender. Sam in the Viet Nam war. But, as an afficionado of war memorials, I have never seen any of this mentioned on war memorials. War memorials serve a particular purpose. Just as actual memorials when we recall a fallen brother or sister. These are not times for politics, Not even important urgent politics, like race relations.

Tom

Debra, I appreciate your civility. I agree on your thoughts about approval. Historically, the management at Gettysburg often enforced the same rules differently, or hardly at all, during different monument proposals. It wasn’t exactly uniform.

Civil War discussion aside, you get points for making a Walking Dead reference. 😉