Civil War Myth-busting: R. E. Lee, Warmonger or Peacemaker?

When I initially uploaded this article, it was called “Myth-busting.” The concept is in honor of one of my favorite non-history shows, Mythbusters (with the original cast). I had not seen Ryan Quint’s ECW blog, “Civil War Myth busting: The Fictional Irish Brigade at Gettysburg.” Check it out if you missed it. Since “Civil War Myth-busting” is such a great title, I’m reusing it. Let’s bust a myth!

There are a lot of historical myths out there. Some stories are actually true; some fall into a gray zone, and others are outright false. This is an oldy but goody. “General Robert Lee relished war.” But did he really? Or was he more of a peacemaker?

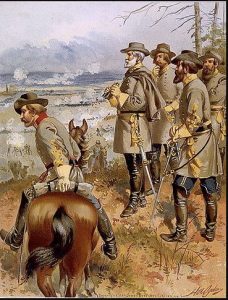

There are two quotes to which historians use to defend their belief that Lee took pleasure in war. During the Battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862, he reportedly stated to Lieutenant General James Longstreet: “It is well this is so terrible! We should grow too fond of it!”[1] This was right after Longstreet’s men obliterated yet another Union brigade on Marye’s Heights. The second quote revolves around Longstreet’s description of Lee on July 1, 1863. He “was excited and off his balance was evident on the afternoon of the 1st, and he labored under that oppression until enough blood was shed to appease him.”[2]

Let’s tackle the statements in chronological order. I don’t believe General Lee made that comment at the Battle of Fredericksburg. For one, Longstreet never mentions this quote in his memoirs. None of Lee’s staff officers noted this remark either. You’d think one of them would’ve recalled the incident if it had occurred. Who then started this story? John Esten Cooke initiated it. He wrote a biography on Lee in 1871. He was a novelist and poet—hint. During the Civil War, he served on Major General J.E.B. Stuart’s staff. Stuart was on the far right of the Confederate line at Fredericksburg, nowhere near Lee’s observation post. Maybe Cooke took a dispatch over to the General? That still doesn’t add up. Cooke notes Lee “murmured” these profound words. A murmur is a mumbled whisper. How did anyone hear it, even if there was a lull in the fighting? There are still horses neighing, whinnying, and wounded soldiers crying out.

Lee, moreover, wasn’t a philosopher. He was a consummate professional Soldier. What does a commander say to his subordinates in the midst of battle? It’s not a trick question. You don’t have to be a combat veteran or tactician to figure this out. A general is going to calmly direct his men to: “Get me the reports from Jackson’s sector.” “Fill the Gaps.” “Get your men ready for the next attack.” “Make sure your artillerymen replenish their ammunition.” Any of these statements make sense. Why would Cooke ad lib then? We can chalk it up to Victorian-style poetic license.

Now, for the sake of discussion, let’s do the “if” game. What if Lee declared: “It is well this is so terrible! We should grow too fond of it!” We need to put this in context. His young soldiers were kicking their opponents’ butt, badly! That’s the sight every leader wants to see. At the same time, it was a picturesque, thrilling scene to watch the Union regiments charging up Marye’s Heights. The blue-clad lines marched in step with fixed bayonets gleaming in the sun. Their national, state, and regimental flags lapped in the wind. The smoke crept over the landscape. It was eerily captivating. But we all know this scene didn’t last. Lee saw a flash. He heard the huge crash of volleying rifles and cannon roaring. In an instant, all that youth and bravery turned to sheer horror, gore, and despair. The scene was terrible.

It’s mysterious then that Longstreet implies Lee displayed a lust for blood during the Battle of Gettysburg. There are two possible reasons he did this. The former may have misconstrued his commander’s quest for a decisive victory for blood lust. Lee’s crusade required that he use extreme, constant violence at the tactical and theater of operations levels. He was fixated on, possibly even infatuated with, aggressive tactics. Longstreet may also have wanted to discredit Lee. After the latter’s death, the former got drawn into a running post-war debate with Lee’s staff officers. It was an unfortunate situation. I tend to lean, though, toward Longstreet misinterpreting his general’s intent. The two definitely disagreed about attacking the Union line at Gettysburg.

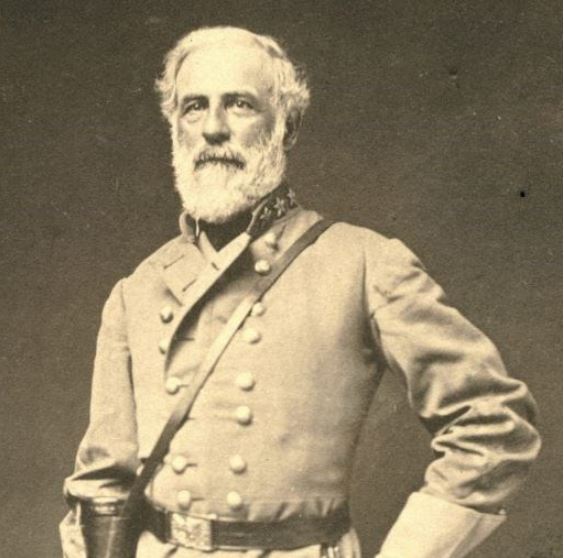

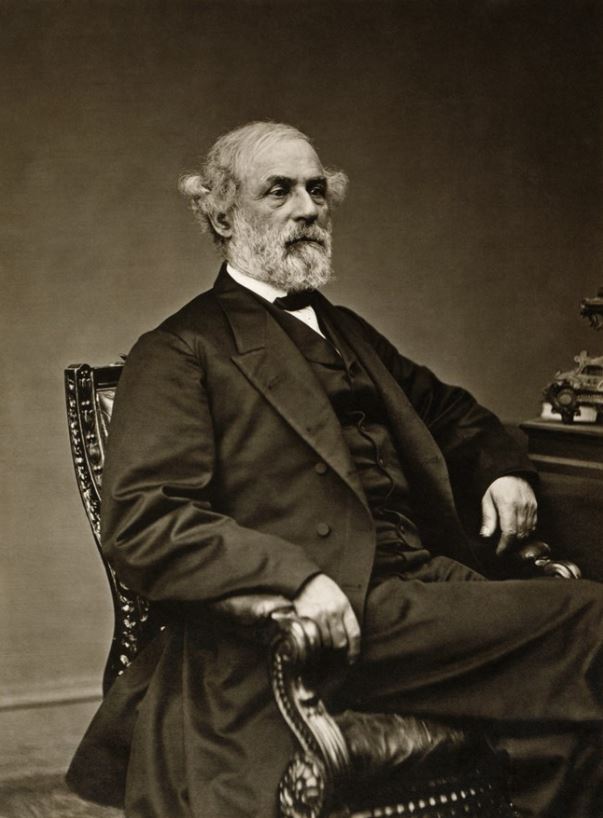

For all of his professional determination to employ aggressive tactics, the paradox is that General Lee preferred peace over war. He deeply loved and admired the rank and file. Lee loved his senior generals as well. History records that he openly broke down on separate occasions when he heard that Jackson, Stuart, and Hill had fallen. Lee despised the destruction. It’s no surprise then that he urged his soldiers to peacefully return home after he surrendered at Appomattox Courthouse. And he followed his own advice. After the conflict, he served as President of Washington College, educating America’s future leaders. He forgave his enemy. Upon request from the Federal government, he humbled himself and attended several Congressional hearings in Washington. His correspondence also indicates he promoted peace. When some disgruntled Confederate officers decided to move their families to Mexico, Lee wrote to one of their leaders.

“We have certainly found our form of government all that was anticipated by its original founders; but that may be partly our fault in expecting too much and partly in the absence of virtue in people. As long as virtue was dominant in the Republic so long was the happiness of the people secure . . . the great teachers of men under the guidance of an ever-merciful God, may save us from destruction and restore to us the right hopes and prospects of the past . . . I shall be very sorry if your presence be lost to Virginia. She has now need for all of her sons, and can ill afford to spare you.”[3]

Lee could’ve replied. “I’ll come down to Mexico with you, and we can continue the fight against the Federal government.” Nope, he let go of the violence and animosity. He committed the rest of his life to the healing of the nations and bringing peace to the Republic.[4]

[1] John Esten Cooke. A Life of General Robert E. Lee (New York: G.W. Dillingham Co. Publishers, 1871), 184.

[2] James Longstreet. From Manassas to Appomattox: Memoirs of the Civil War in America (Philadelphia, PA: J. P. Lippincott, 1896), 384.

[3] J. William Jones. Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee: Soldier and Man (New York: Neale, 1906), 389. Lee was writing to Captain M. F. Maury. He and several other officers resettled their families in Mexico after the war. It’s an interesting piece of history that gets lost.

[4] List of Illustrations: Illustration 1: General Lee, Virginia Historical Society, https://www.nps.gov/arho/learn/historyculture/office.htm; Illustration 2: General Lee at Fredericksburg, H.A. Ogden, Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/92508932/; Illustration 3: Irish Brigade charging up Marye’s Heights, painting by Don Troiani; Illustration 4: General Lee at his Headquarters, Gettysburg, painting by John Paul Strain, https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/significance-lees-headquarters-gettysburg; Illustration 5: “Give them Cold Steel,” Lew Armistead’s Virginians breach the wall, July 3, 1863, painting by Don Troiani; Illustration 6: Robert E. Lee, President of Washington College, 1867, https://www.nps.gov/arho/learn/management/national-memorial-to-robert-e-lee.htm.

Thank you so much for this.

Well-done.

Regarding Longstreet’s statement, after 28 years in the Army, Reserves, etc., I can say *every* subordinate has some opinion on what what motivates the “old man” – i.e., the commander. That is just human nature. That does not make Longstreet more insightful than any other subordinate.

Tom

Just notice typo in Lee letter to Maury:

“We have certainly NOT found our form of government all that was anticipated by its original founders; but that may be partly our fault in expecting too much and partly in the absence of virtue in people. As long as virtue was dominant in the Republic so long was the happiness of the people secure . . . the great teachers of men under the guidance of an ever-merciful God, may save us from destruction and restore to us the right hopes and prospects of the past . . . I shall be very sorry if your presence be lost to Virginia. She has now need for all of her sons, and can ill afford to spare you.” (Emphasis added.)

So, is the claim then that Lee never said it? For someone to be on a general’s staff (like John Esten Cooke), I think it’s well to conclude that they had particular talents and/or attributes that served that general’s needs, regardless of vocations or occupations like those of “poet” or “novelist”. Over the course of a battle and/or campaign, things can get confused. Research and scholarship often shows that units and personnel were NOT where they have been reported to be in historical works. Forensics applied to battlefields often result in some surprising, and contradictory, facts as opposed to what the ‘official’ records purport. Lee, and all who participated on both sides, no doubt had their “blood up” as battles unfolded. Battles become more tribal than anything else. Few if any are believing “Let’s do this for the flag”, or “Mom’s apple pie”, or “my right to own another human being”. It is “us against them”, and “kill or be killed’. Watching your enemy mowed down in great numbers has to be a satisfying, gratifying experience, especially when YOUR plans and tactics are facilitating such a result. That doesn’t imply being a warmonger, it is simply human nature.

There are tales and stories of soldiers on both sides risking their own lives to help wounded foes escape the flames that were imperiling them at the Battle of the Wilderness. I’ll bet my last dime there were some, on both sides, who upon hearing the screams of their foes being consumed by those flames, thought “Let them burn”.. Again, terrible as it might be, it is human nature, at least among some. The point is, historians have cited and referenced Lee’s quote for multiple generations. So did, and do, they ALL have it wrong? Were they all duped? Which begs another question: are today’s historians to be considered “better” than those of yesteryear? I think that’s a fair and interesting question. I do not ask that in a disrespectful way, I think it can be fodder for a worthwhile discussion. I admire ALL who take up that mantle.

As for Longstreet’s quote, the aftermath of the War certainly had some ugly back-and-forths among leaders that were played out in the media of the times. Accusations, backstabbing, CYA, etc., it all often took place in main-stream publications. I’ll just leave it there.

I take “It is well this is so terrible! We should grow too fond of it!” as seeing the grandeur of the armies being thrown away in the terrible nature of war. I have read very similar accounts of battle from Union officers/soldiers, especially after the gory post-battle work to care for the dead and wounded.

Col. Lee did not sit out the war as a peacemaker. He broke his oath and fought his country that educated and paid him a salary for 35 years. We don’t know what was said by whom but he didn’t go on a long cruise in the Mediterranean in 1861. He stayed and chose violence.

He didn’t violate his “oath.” He resigned his commission so the oath was cancelled.

I will concede that point on the oath state vs country can be debated. I would like to see the original pre 1861 vs post dug into more. Was Washington’s Army officers allowed to resign and change sides?

The question of Col. Lee ( retired) being a man of peace is very thick. The first and only ceasefire I am aware of is that of Appomattox.