Henry O. Flipper: From Slavery to Freedom to West Point

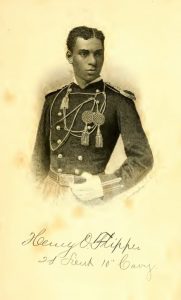

“Mine eyes have seen the glory…” echoed an anthem associated with the arrival of freedom for enslaved families and their children across the South. For one nine-year-old, that song symbolized the “salvation” of freedom[i] and his life became a salute and a challenge toward recognition and equality during the Reconstruction Era. Henry Ossian Flipper — enslaved from birth until 1865 — studied diligently and became one of the first five African American cadets at West Point Military Academy. Though others matriculated ahead of him, Flipper was the first African American cadet to graduate: Class of 1877.Born on March 21, 1856, in Thomas County, Georgia, Henry was the eldest of five children in his family. Festus Flipper, a skilled shoemaker and carriage trimmer, purchased his wife and young son—preventing the splitting of their family when their enslavers were moving. Though still in slavery, the Flipper family reunited and lived in a community with approximately 65 other enslaved people, most of the men working as mechanics in a new manufactory venture near Atlanta. In later years, Henry Flipper remembered that this community “accumulated wealth” from hiring themselves out for various jobs and “lived happily” but lacked “absolute freedom and education.”[ii] Surprisingly, an educational opportunity came and was actually endorsed by the white woman who controlled the lives these enslaved families. “one of the mechanics, who had acquired the rudiments of an education, applied to this dissolute mistress for permission to teach the children of her ‘servants.’ She readily consented, and, accordingly, a nightschool was opened in the very woodshop in which he worked by day. Here young Flipper was initiated into the first of the three mysterious R’ s, ‘reading, writing and Arithmetic.’”[iii]

In 1864 as Sherman’s army advanced on Atlanta, the Flipper family was forced to relocate to Macon, Georgia. The following year with the Union victory and collapse of the slavery system, the Flipper family chose to return to Atlanta, settling up a home for themselves in one of the still-standing buildings. In the following years, Henry Flipper attended several different schools established and operated by the American Missionary Association, then transferred to the Atlanta University in 1869.[iv] Congressman from the Fifth District, J.C. Freeman recommended Flipper’s appointment to West Point, and in due time, official correspondence made its way to the Flipper residence. Henry had been accepted for cadetship at the U.S. Military Academy.

On May 20, 1873, Flipper arrived at West Point. He had insisted on traveling without announcement in the newspapers, fearful that he would be harassed or worse on his journey from Georgia to New York. When from the “little ferry-boat…viewed the hills about West Point, her stone structures perched thereon, thus rising still higher, as if providing access to the very pinnacle of fame,” he shuddered. Flipper had heard numerous stories “horrors of the treatment of all former cadets of color,” and he approached “tremblingly yet confidently.”[v] And his first day proved difficult. “Fear and apprehension” plagued every step as he went through reporting and in-processing, expecting “every moment to be insulted or struck…and that my life there was to be all torture and anguish.”[vi] Later, with hindsight, Flipper admitted that he was not physically abused in ways that he had feared, but for the next four years, he endured daily mental and sometimes emotional abuse from those within and outside the barracks.

To the regular visitors—civilian and military—to West Point, Flipper seemed like an attraction. Adults and children pointed at him, staring and remarking they had seen “the colored cadet” or using insulting epitaphs. In the words of one white man, “You are quite an exhibition yourself. No one was expecting to see a colored cadet.”[vii] He avoided newspaper reporters as much as possible, trying to stay invisible to the outside world and focus on his studies and military training.

Treatment from his fellow cadets varied, but he had no friends. Later, Flipper wrote: “When I was a plebe [freshman] those of us who lived on the same floor of barracks visited each other, borrowed books, heard each other recite when preparing for examination, and were really on most intimate terms. But alas! in less than a month they learned to call me “nigger,” and ceased altogether to visit me. In camp, brought into close contact with the old cadets, these once friends discovered that they were prejudiced, and learned to abhor even the presence or sight of a ” d—d nigger.”[viii]

Loneliness and ostracism was real in Flipper’s West Point experience. There were reasons that other African American cadets dropped out of the academy, but Flipper determined to stay, withdrawing as much as possible from the social aspects and focusing on his studies. He struggled with how to describe his years at the academy and the treatment from fellow cadets, writing numerous illustrations of mistreatment and kindness — a situation that was confusing at best and deeply racist at worst. Responding to the common inquires “What is the general feeling of the corps towards you ? Is it a kindly one, or is it an unfriendly one. Do they purposely ill-treat you or do they avoid you merely ?” Flipper later wrote:

I have found it rather difficult to answer unqualifiedly such questions; and yet I believe, and have always believed, that the general feeling of the corps towards me was a kindly one. This has been manifested in multitudes of ways, on innumerably occasions, and under the most various circumstances. And while there are some who treat me at times in an unbecoming manner, the majority of the corps have ever treated me as I would desire to be treated. I mean, of course, by this assertion that they have treated me as I expected and really desired them to treat me so long as they were prejudiced. They have held certain opinions more or less prejudicial to me and my interests, but so long as they have not exercised their theories to my displeasure or discomfort, or so long as they have “let me severely alone,” I had no just reason for complaint. Again, others, who have no theory of their own, and almost no manliness, have been accustomed “to pick quarrels,” or to endeavor to do so, to satisfy I don’t know what; and while they have had no real opinions of their own, they have not respected those of others. Their feeling toward me has been any thing but one of justice, and yet at times even they have shown a remarkable tendency to recognize me as having certain rights entitled to their respect, if not their appreciation. As I have been practically isolated from the cadets, I have had little or no intercourse with them. I have therefore had but little chance to know what was really the feeling of the corps as a unit toward myself. Judging, however, from such evidences as I have, I am forced to conclude that it is as given above, viz., a feeling of kindness, restrained kindness if you please.[ix]

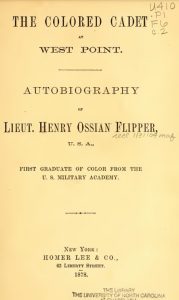

It can be heart-wrenching to read that Cadet Flipper expected nothing better. Throughout his memoir “The Colored Cadet at West Point”, published in 1878, he offered his thoughts and hopes for equal treatment and genuine kindness while expressing doubts that culture would permit for equality. It’s as though he has accepted the context and the racism that was prevalent in society and at West Point during that time, yet he wanted to find a way to live in that context and try to win respect. At times in his writings, he probably downplayed the difficulties and insults and the volume in some areas reads like a manual from a trailblazer for the next cadets who would follow in his footsteps through the racism of 19th Century West Point.

Cadet Henry Flipper stayed. Determination and an extraordinary willingness to see the best in other people and offer them respect when they deserved it characterized his four years at West Point. Finally, in 1877, graduation day and commissioning arrived. While the newspapers printed columns reacting with pride, astonishment, and confusion over the news, Flipper took in the moment in a personal way, finding a small victory among his fellow cadets:

Even the cadets and other persons connected with the Academy congratulated me. Oh how happy I was! I prized these good words of the cadets above all others. They knew me thoroughly. They meant what they said, and I felt I was in some sense deserving of all I received from them by way of congratulation. Several visited my quarters. They did not hesitate to speak to me or shake hands with me before each other or any one else. All signs of ostracism were gone. All felt as if I was worthy of some regard, and did not fail to extend it to me. At length, on June 14th, I received the reward of my labors, my ” sheepskin,” the United States Military Academy Diploma, that glorious passport to honor and distinction, if the bearer do never disgrace it.[x]

Graduating 50th out of 64 in the Class of 1877, Flipper commissioned as a second lieutenant. He became the first Black officer in the 10th U.S. Cavalry and served at forts and outposts in the west until 1881. Accused of embezzlement by white officers, Flipper faced court martial and was found not guilty. However, the court martial determined he had acted “unbecoming of a gentleman” and he was dismissed from the Army in 1882. Until his death in 1940, Flipper maintained his innocence and protested that he had been treated unjustly by the dismissal. In his civilian life, he held several important government and private engineering positions. Some of his governmental work included Special Agent of the Justice Department and a special assistant to the Secretary of the Interior for the Alaska Engineering Commission and aide to the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. His expertise included research and understanding of Mexican land and mining laws. Flipper also became an accomplished author and wrote several books for the Department of Justice and personal recollections about his experiences.[xi]

During his lifetime, Flipper petitioned Congress for “that justice which every American has the right to ask” and a reexamination of his court-martial and dismissal. In 1898, a bill was introduced to Congress that would have restored his rank and instated him in the Army, but the legislative attempt failed. After his death, Flipper’s descendants continued to advocate for a reexamination. In 1976, the Army officially changed his dismissal to an honorable discharge. Then, in 1999 President Bill Clinton issued a full pardon, saying this was about “a moment in 1882 when our government did not do all it could do to protect an individual American’s freedom…. The man we honor today was an extraordinary American. Henry Flipper did all his country asked him to do.”[xii]

Henry Flipper’s life and his experiences at West Point were embedded in a society that did not act upon equality. The context of his four years at the academy and five years of military service is troubling, considering the insults and racism that he faced on a daily basis. The context is not worthy of pride and is not a shining moment. However, through that adversity, Flipper’s courage, commitment, and sheer determination is a brilliant moment and inspiring story of persevering. He was a trailblazer for African American officers in the U.S. Military and helped to write the first chapters of a legacy of service which is honored, remembered, and continued to this day.

Through the verbal cruelties and ostracism endured at West Point, Flipper seemed aware that he was making history. He described one of his proudest moments in the West Point uniform in a scene that took place away from the post.

While walking down Sixth Avenue, New York, with a young lady, on a beautiful Sabbath afternoon in the summer of 1875, I was paid a high compliment by an old colored soldier. He had lost one leg and had been otherwise maimed for life in the great struggle of 1861-65 for the preservation of the Union. As soon as he saw me approaching he moved to the outside of the pavement and assumed as well as possible the position of the soldier. When I was about six paces from him he brought his crutch to the position of “present arms,” a soldierly manner, in salute to me. I raised my cap as I passed, endeavoring to be as polite as possible, both in return for his salute and because of his age. He took the position of “carry arms,” saying as he did so, “That’s right! that’s right! Make me glad to see it.” We passed on, while he, too, resumed his course, ejaculating something about “good-breeding,” etc., all of which we did not hear. Upon inquiry I learned, as stated, that he had served in the Federal army. He had given his time and energy, even at the risk of his life, to his country. He had lost one limb, and been maimed otherwise for life. I considered the salute for that reason a greater honor.[xiii]

There is something electric in the account. An African American veteran from the Civil War saluting the first African American cadet who would graduate from West Point. An acknowledgement of the legacy of courage through a chance encounter and salute on a New York street. The older veteran had been among the first to wear the Federal uniform. The younger soldier among the first to enter West Point and the first to commission into the officer corps from the academy. Their lives were not easy, their struggles were evident. But they recognized each other’s service and sacrifices and how it would help to change a nation beyond their lifetimes. Perhaps their eyes could “see the glory” of the future shining with more equality and the establishment of Civil Rights, and they were helping to write that history “with rows of burnished steel” from the Civil War battlefields or the parade field at West Point.

Sources:

[i] Henry Ossain Flipper, The Colored Cadet at West Point (New York: Homer & Lee, Co., 1878). Accessed through archive.org: https://openlibrary.org/works/OL16583667W/The_colored_cadet_at_West_Point?edition=ia%3Acoloredcadetatwe00flip#editions-list Page 9-10

[ii] Ibid., Page 9.

[iii] Ibid., Page 11.

[iv] Ibid., Page 13.

[v] Ibid., Page 29.

[vi]Ibid., Page 35.

[vii]Ibid., Page 119.

[viii] Ibid., Page 120.

[ix] Ibid., Pages 124-125.

[x] Ibid., Page 244.

[xi] Library of Congress Featured Documents, Henry O. Flipper https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/henry-flipper

[xii] President William J. Clinton’s Comments Honoring Lt. Henry O. Flipper https://history.army.mil/html/topics/afam/clinton_flipper.html

[xiii] Henry Ossain Flipper, The Colored Cadet at West Point (New York: Homer & Lee, Co., 1878). Accessed through archive.org: https://openlibrary.org/works/OL16583667W/The_colored_cadet_at_West_Point?edition=ia%3Acoloredcadetatwe00flip#editions-list Page 226-227

Thanks for this very interesting account of Henry Flipper’s journey, including his appointment to West Point, struggle to graduate but yet he made it. I would like to hear more about his appointment. J. C. Freeman was a former Confederate and yet had the courage to nominate Henry Flipper. He chose a good man.

That’s a great idea. I thought “there must be a story” in Freeman’s appointment decision, too. Maybe there will be another post!

Moving story, very well written, and timely. Thanks

President Clinton signed a full pardon in the case of LT. Henry Flipper in 1999. The third Black Cadet from West Point, Colonel Charles Young is also an amazing story. Colonel Young would have been promoted to General except he was Black. Both Flipper and Young are true stories in courage.

thank you Sarah for this beautifully written tribute to a great American.