“The Sound of the First Gun”: The Bombardment of Fort Sumter Observed at a Distance

It’s the anniversary of the firing on Fort Sumter, the traditional beginning of the American Civil War (April 12, 1861). In the April 20th edition of The Charleston Daily Courier, I found the following account by a correspondent using the pen name “Omega.”

The perspective of Confederates observing the bombardment at a distance seemed interesting, along with the emphasis that they were doing their duty, though not at the scene of action. Perhaps these men of the Rutledge Mounted Rifles — like many others on both sides — feared that the fight was over and peace would quickly follow, before they had their chance “see action.”

Special Correspondence of the Courier.

Camp Simons, Rutledge Mounted Rifles, April 19, 1861.

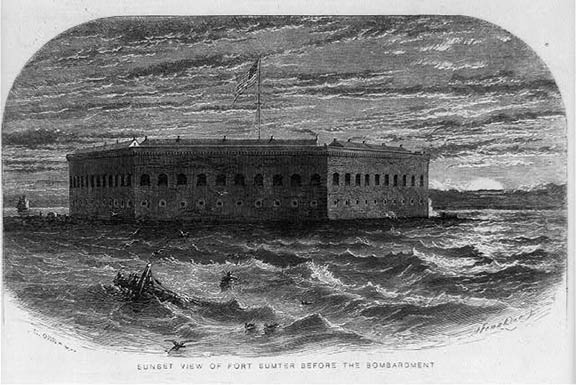

Hard along the banks of this classic stream, one of the inlets to the waters of the bay, and though which “high military authority” at Washington have deemed it “far from impossible” to slip in forces in boats of a certain draught, has our patriotic young corps kept watch and ward for six long weeks, by day and night, in three separate detachments. Prevented by our other important duties as well as our peculiar organization from sharing in the glorious action of the 13th, to our lower detachment alone was permitted the view of the contest. Gathered in groups upon the point extending out into the marsh, and from which a full view of the fort was obtained, we watched every flash from her guns and the answering volleys from Moultrie and the Island guns and the Floating Battery, of all which our glasses gave us a fair view.

I will not attempt to describe our emotions as from the sound of the first gun our boys leaped from their tents and knew the battle had begun, nor through the long hours of those two eventful days. Suffice it that though our duties kept us where we were, our souls and hearts were in those heavy batteries, and our hands too would have been there had they been so allowed. But fate and General Beauregard had ordered otherwise. Dows from the heavy guns on Stono mouth to the waters of Ashley, have we kept our long watch and ward, with flaming rocket, swift horse and sure rifle, for sometime backed by the bayonets of the Columbia Greys at our lower camp, and other reserves within easy reach.

Here our four gun battery stands planted on the bluff, with the pieces ready for their work, ball for long range, something other than cans of preserves for close entertainment. Cadets Walker, Palmer, Guerard, and Thursion, of the Citadel Academy, are in charge of the pieces, and under their effective drill our detachment has become reliable for their proper working, and should any of the “gallant navy” try the “boats of a certain draught” adown the back stretch, they will hear from us first, you afterwards.

As I write, we have just finished our daily morning drill, during which we have waked the echoes of the winding shore considerably, and the fellows are now doing whatever seems meet to each one (within the rules). On the night of the 13th we heard heavy firing, apparently from the Stono Batteries, at half-past nine P.M., and soon after an express came from Lieut Trenholm’s station to report five rockets and several guns from Battery Island. The call was immediately given to the guns, where our boys remained until the small hours had begun to glide by, and with rifles and infantry in position waited patiently enough — the signal fires and rockets that were to announce our enemy at hand. But none such relieved the darkness, and, with proper watch set, many of our men folded their blankets around them, and quietly slept beside the guns until the advancing hours told us that looking out was profitless.

Soon the men were marched back to quarters, and the sentries alone kept their ceaseless round. We afterwards learned that the rockets and guns were only the signals of rejoicing on the surrender of Fort Sumter.

Spring has opened her treasures of beauty, and breathed her perfumed gales, but wars and rumors of wars have crowded so fast upon us that, alas, we have not been so mindful of her gentle influences and her joyous notes.

Well, so be it; sad though she slide around seven times unheeded amid the din of battle, we will yet, when we have rolled its tide far away from our shores, rejoice with her and her gentle companion Peace.

What strikes you about the early letters from the war is the cloying romanticism and delusional beliefs about what combat would entail. It’s as if they thought it was a brief fist fight, followed by the pretty, handkerchief waving, deeply sighing local belles wiping off their sweaty brows. What a wake up call reality would be!

And only hours after firing commenced at Charleston Harbor, 500 miles away to the southwest hundreds of Federal reinforcements were landed at THE OTHER potential flashpoint: Fort Pickens at Pensacola. This deliberate “violation of the Pickens Truce” by President Lincoln enraged Rebel commander Braxton Bragg when he awakened to the news on the morning of 13 April 1861… but it was a fait accompli cementing Federal control of Fort Pickens Florida for the duration of the war.

As mentioned, General Bragg was enraged when he awoke Saturday morning 13 April and discovered that USS Brooklyn, hovering south of Fort Pickens in the Gulf of Mexico since January, had unloaded soldiers and equipment, resupplying Fort Pickens in violation of the Truce negotiated by ex-Senator Stephen Mallory and President Buchanan. Someone must be held responsible; and Bragg fixed his ire on the Federal messenger whom he’d chatted with on Thursday and generously permitted aboard the Flag of Truce boat, USS Wyandotte to complete that man’s journey to Fort Pickens. Alerts were immediately telegraphed from Pensacola north to “Cancel the pass and detain the U.S. Naval Officer travelling by train on his return to Washington.” Just short of Montgomery, Confederate law enforcement boarded the overnight Florida & Alabama and took into custody that naval officer. He was deposited in the Montgomery City Jail, deemed a Prisoner of War. And John L. Worden, Lieutenant U.S. Navy and future commander of the Monitor, remained a “guest of the Confederacy” until November 1861.