The “Fighting Naturalist” of the 19th Massachusetts

It was hot and muggy most of the time. It rained frequently and the men made acquaintance of the “wood tick,” and enumerable bugs and specimens of insect life hitherto unknown to them. The very earth moved with “new life.” Sticks and twigs were endowed with motion. The men would watch a black twig two or three inches long, apparently dead wood among the leaves, when it would scamper off and the acquaintance of a new insect called the “walking stick” was made, although it was a very old inhabitant of this section. They had the “Gold Bug,” not the political specimen of later days but a handsome round yellow “feller.” Lieut. James G. C. Dodge, of Company F, made quite a collection of these bugs.

It was a common thing to see two or three men, huddled together, poking at something on the ground. Others would join them on the run. Soon a crowd would collect, running and yelling, “What’s Up?” Some one of the crouchers would answer, “Oh, got a new bug,” and the crowd would laugh and disperse. Like everything else, this was soon an old story and “buggy” was immediately dispatched, given to the lieutenant for his collection, or allowed to fly or run away…[i]

Wild times, indeed, in the camp of the 19th Massachusetts Infantry during the Peninsula Campaign in the spring of 1862. But who was James G. C. Dodge?

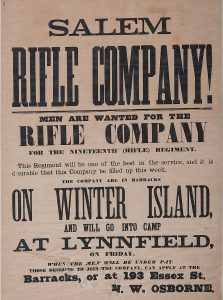

According to his military record, James Gordon Clarke Dodge was born about 1840 and lived in Boston.[ii] He enlisted in 1861 as a second lieutenant in the 19th Massachusetts Infantry, beginning his service in Company F. The regiment and Dodge, saw action at the battle of Ball’s Bluff in October 1861, and in the night after the battle, Dodge commanded part of the Union picket line and tried to organize a rescue party for the Federal wounded calling for help across the water.[iii]

The next morning he was tasked with rowing across the river under flag of truce at the Confederates’ request to retrieve the wounded. The regimental historian later recalled that Dodge “went over in the skiff…dressed in a pair of private’s trousers…a pair of old army shoes, a blouse with shoulder straps, sword and revolver. A dirty, ragged gray blanket was thrown over his shoulders like a shawl and his glazed cap cover hid the bugle on the front of the cap.”[iv] His lack of insignia caused trouble when he reached the other side. Accompanied by a willing-to-be-helpful Confederate enlisted man, Dodge tramped up and down the bluffs looking for an officer to make the truce official and allow the removal of the wounded. When they finally found a Confederate officer, the man doubted Dodge’s appearance and story.

“Stepping on a small stone near by, the lieutenant drew himself up to his full height (five feet, three inches), jerked the blanket from his shoulders and replied as gruffly as he could, pointing to his shoulder straps. “There are my credentials” and then turned his back upon the rebel officer, who rode away, growling: “Well, you ought to have credentials.”[v] Eventually, Dodge met Colonel Jenifer who arranged that Dodge could bring about a dozen men back to Ball’s Bluff to bury the dead.

In the spring of 1862 the regiment transferred to the Virginia Peninsula where the bug collecting flourished. Throughout the regimental history, Dodge appears to have been an officer who went out of his way to be useful and who treated his enlisted men with politeness while maintaining command. During the fighting around White Oaks Swamp and Glendale at the end of June, “the little lieutenant expressed his willingness to remain on duty until morning, knowing that all the others were thoroughly exhausted.”[vi]

Dodge survived the Peninsula Campaign physically unscathed, and while the regiment rested in camp near Harrison’s Landing during General McClellan’s “strategic change of bases,” the want-to-be-naturalist found more to study than insects. According to the regimental history, “Lieutenant Dodge appeared one day with a huge black snake.” Other men also had snake adventures. “One man pulled an adder from his trouser leg, and soon after a copperhead was discovered to have “turned in” along with two tent mates.” If Dodge was still studying bugs, he had plenty of specimens, too. “Mosquitoes were less frequent here than at Fair Oaks, but every kind of insect abounded.”[vii]

Company F took pride in their first lieutenant. During the late summer campaigning, the unit encountered some ninety-day enlistees who eyed the 19th Massachusetts.

“Who’s that fellow?” pointing to Lieut. James G. C. Dodge, of Company F, who stood near, arrayed in a soldier’s blouse.

“That,” said the man addressed, “is our lieutenant.”

“The Devil! Well, he’d be a rough customer to meet in the woods alone.” (Those who knew Lieut. Dodge’s 5 feet 3 inches will appreciate this remark the most.)[viii]

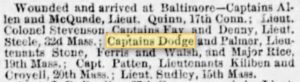

During the battle of Fredericksburg in December 1862, Lieutenant Dodge was wounded. Casualty reports differ on the details and severity of his injury. One report says he was wounded in the abdomen[ix], another claims in the “breast, severe.”[x] However, a newspaper report from December 17, 1862, stated that “Capt. Dunn and Lieut. Dodge, both of Boston, are here, slightly wounded, but able to walk about.”[xi] There is a possibility that it’s another Lieutenant Dodge, but the little lieutenant of the 19th Massachusetts did survive his injury and returned to duty.

Dodge switched companies several times during his service. At some point, he had transferred from Company F to Company D.[xii] He also promoted to captain in April 1863.[xiii] Presumably, Dodge fought with his regiment at Marye’s Heights and Salem Church during the Chancellorsville Campaign in May 1863. During the battle of Gettysburg, the 19th Massachusetts—part of Gibbon’s Division of the II Corps—helped to defend Cemetery Ridge as the Union III Corps broke in their advanced position on July 2. One of the regiments that General Hancock threw into the fray to delay the Confederate surge, the 19th was caught in an enfilading fire and was about to be captured. “The Nineteenth is ordered to rise and fire a volley, which temporarily checks the enemy. They are instantly told to face about and march back” leaving “Major Rice and about 70 of the men…behind as skirmishers to protect the left of the line.”[xiv] The delaying action helped and also set the stage for the charge of the 1st Minnesota. The 19th Massachusetts also helped to repulse Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble’s Charge on July 3, counterattacking to aid in re-securing the center of the Union line.

At some point in the action on July 2 or 3 at Gettysburg, Lieutenant Dodge was wounded, and he is listed with the casualties of Company H, suggesting he led that part of the unit in the fight. The regiment history claims he was wounded on both July 2 and 3, which technically could be possible if his first wounding was slight, but could also be an error in the records.[xv] His name does appear on the list of casualties sent to Baltimore in the July 6 edition of the Boston Evening Transcript.[xvi] Dodge spent time on “detached service” in the later months of 1863, suggesting he may have had a longer recovery. In the November 1864, Dodge mustered out of the 19th Massachusetts and transferred to the 61st Massachusetts, promoting to major.[xvii]

Dodge’s post war life and activities have been more challenging to track. It appears that he applied for a passport in 1866, suggesting he did some international travel.[xviii] He may have also traveled in 1857 since a 17-year-old is with the same name and initials is listed on a passenger list, arriving in Boston after a voyage from Liverpool.[xix] Marriage records were not easily discovered, and he may have stayed single. He died on January 14, 1877, in Creston, Iowa, according to his military/veteran records.[xx]

While my research did not turn up a good reason for Dodge’s interest in bugs, that collecting and the men’s enthusiasm for their little lieutenant’s hobby perhaps speaks volumes about his leadership and respect.

Research Notes:

There may be more information that will come to light about James G. C. Dodge. It appears that a personal family genealogy site might have more information or possible even diaries, but their current formatting to share the materials is out of date or unsupported, and unfortunately I could not access the resources while doing this research.

Surprisingly, I have not yet found a photograph of Lieutenant Dodge.

The title phrase “fighting naturalist” is borrowed from the Napoleonic era movie Master & Commander: The Far Side of the World. Jon Tracey made the name connection between Dodge’s accounts and one of the movie characters during a discussion some months ago. Thanks!

Sources:

[i] Ernest Linden Waitt, History of the Nineteenth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1906. Page 73. (Accessed through Google Books).

[ii] Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines in the Civil War; Register of the Commandery of the State of Massachusetts MOLLUS; Photo courtesy of Massachusetts Commandery of MOLLUS; Union Blue: History of MOLLUS. (Accessed through Ancestry.com)

[iii] Ernest Linden Waitt, History of the Nineteenth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1906. Page 25. (Accessed through Google Books).

[iv] Ibid., Page 26.

[v] Ibid., Page 27.

[vi] Ibid., Page 101.

[vii] Ibid., Page 112.

[viii] Ibid., Page 122.

[ix] Ibid., Page 181.

[x] Ibid., Page 187.

[xi] Boston Evening Transcript, Wednesday, December 17, 1862. Accessed through Newspapers.com

[xii] Ernest Linden Waitt, History of the Nineteenth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1906. Page 211. (Accessed through Google Books).

[xiii] Ibid., Page 381.

[xiv] Ibid., Pages 230-231.

[xv] Ibid., Pages 232, 247, 258.

[xvi] Boston Evening Transcript, Monday, July 6, 1863. (Accessed through Newspapers.com)

[xvii] Ernest Linden Waitt, History of the Nineteenth Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, 1906. Page 254. (Accessed through Google Books).

[xviii] James G C Dodge in the U.S., Passport Applications, 1795-1925. (Accessed through Ancestry.com)

[xix] James G C Dodge in the Massachusetts, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1963. (Accessed through Ancestry.com)

[xx] Massachusetts Soldiers, Sailors and Marines in the Civil War; Register of the Commandery of the State of Massachusetts MOLLUS; Photo courtesy of Massachusetts Commandery of MOLLUS; Union Blue: History of MOLLUS. (Accessed through Ancestry.com)

The descendants of those ticks hopped on a Seven Days tour I was giving.

Large family.

Great work in highlighting yet another aspect that shows CW soldiers’ diversity!