The (Limited) Destruction of Atlanta

Emerging Civil War is pleased to welcome W. Todd Groce, Ph.D., president and C.E.O. of the Georgia Historical Society, based in Savannah. Todd was kind enough to share with us a little treasure from the GHS’s incredible collection.

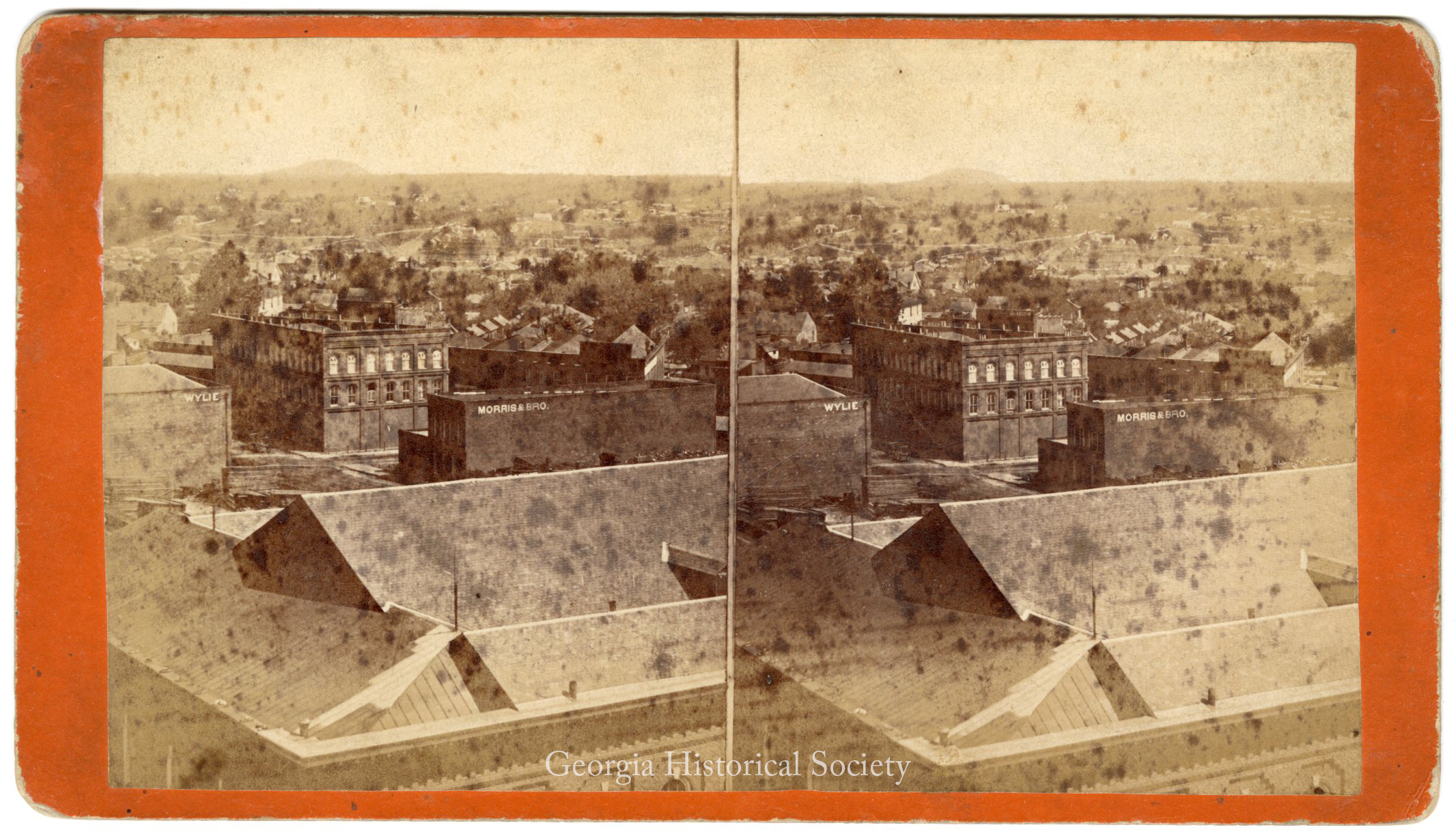

This morning I came across in the photo collection of the Georgia Historical Society a stereoview of Atlanta taken c. 1875 looking east toward Stone Mountain:

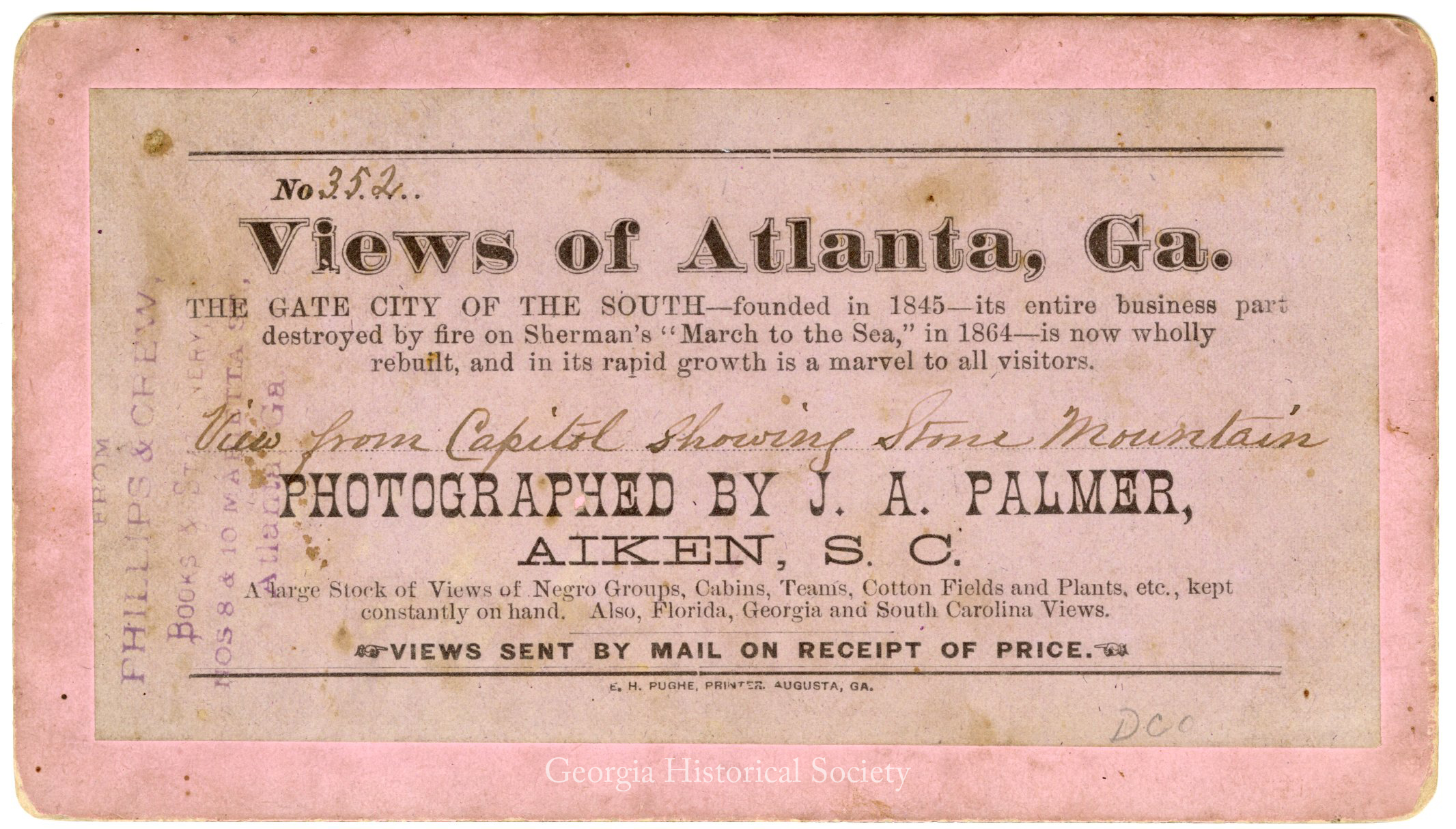

Here’s a look at the reverse side:

Note that on the back it says the “entire business part destroyed by fire” (emphasis added). Not the entire city. This corresponds with the latest estimate by historians that only about 40 percent of the city was destroyed by Sherman. It is also evidence that, before the Lost Cause turned Sherman into a villain, Southerners were willing to admit the limited nature of his destruction.

————

Photo courtesy of: Palmer, J. A. “View from the Capitol Showing Stone Mountain.” Georgia Historical Society stereograph collection, GHS 1361-SG, Georgia Historical Society, Savannah, Georgia.

So, Sherman is only a limited villain, or a 40% villain. That is some improvement, I suppose.

Tom

As I recall, Confederates torched the city on their way out of town, doing more damage than Sherman did.

No, there were basically two different events. Yes, the Confederates burned box cars – containing ammunition, etc. – which then traveled to nearby warehouses. That was when they evacuated the city – allowing Sherman to occupy the city. But, actual burning of civilian homes and shops was Gen. Sherman’s claim to infamy. He even evicted the civilians from the city before torching the place. That was when the formerly anti-secession mayor of Atlanta, James Calhoun protested. Sherman responded with his now semi-famous remark that war is “cruelty” and it cannot be refined. And, you all started this war, he essentially said. Then some 5,000 civilians were forced out.

Some 3,200 to 5,000 homes were burned, for no apparent military purpose. That amounts to a war crime. After the war, Sherman insisted he designated four buildings to be burned and that no private homes were burned. But, we know the amount, more or less, because a Georgia militia colonel was tasked by Pres. Davis to conduct an inventory of the city 2 weeks after the Federals left. See “War Like a Thunderbolt,” p. 342-364.

Col. William Le Duc, Quartermaster of the 20th Corps objected to this forced eviction. Gen. Sherman essentially told him too bad. Le Dec wrote a book after the war in which he provided the numbers of families and households evicted southward. He called it the “Book of Exodus.” As Quartermaster, it fell to him to get the Atlanta residents out of the city. Gen. Sherman did at least provide Federal wagons to help them move southward. A large contingent also went north on the remaining railroad.

Tom

Gen. Sherman also did not burn the hotel in which he had been staying. I suppose this makes him 60% a very generous person.

Tom

Oh my. Is there a “pious cause” bias in evidence here! The caption does not describe the extent to which Atlanta burned. It merely says that the entire business section was destroyed and is now wholly rebuilt. It does not say the business section was all that was destroyed. This is a perfect example of how our modern academia spins the narrative, and has become exactly what the late Dr. Ludwell Johnson warned:

“Various theoretical “isms” arriving from Europe in the 1960’s still endanger the very existence of what has so long been thought of as history… Of all fields of scholarship, history is perhaps most attractive and vulnerable to Political Correctness. It decrees that some things should be accepted without question – otherwise the elaborate machinery of academic control and social hostility will exact their full measure of retribution on the dissenter… Readers with special interest in the period of the Civil War need to be particularly alert because the South and Southerners offer many tempting Targets to the holier-than-thou.”

The modern pejorative “lost cause myth” is itself a myth intended to shut down debate and deter further scrutiny of the evidence. As soon as it is used one should immediately begin to question the veracity of the source. Phillip Thomas Tucker, an honest Ph.D. in American History who served for over twenty years as a Professional historian for the Department of Defense, states, “…too many of today’s historians have been wrong about our past by looking at history through a modern lens and making moral judgements about a time and people for which they have relatively little true understanding, denouncing undeniable facts as nothing more than conservative revisionism and neo-Confederate propaganda.”

The “myth of the Lost Cause” is a fabrication used by agenda driven historians to dismiss, marginalize, and invalidate the Southern perspective of the War, while at the same time promoting a sanitized popular myth. This sanitized myth makes strange bedfellows of neocons on the Right promoting “American Exceptionalism,” and Social Justice Warriors on the Left promoting a neo-Marxist lens through which to view all of history. Both political extremes employ a sanitized version of the war that extends back to a time before the war ended. That mythical version was a war “about slavery” in which egalitarian ideals defeated an evil oppressive slavocracy. For neocons, “American Identity“ is deeply rooted in this myth, which is so foundational to its mantra of American Exceptionalism. For the Left, that same myth provides a poster war for social justice ideology, and a prototype historical example of a white supremacy that, still to this day, they claim permeates our culture, though in less obvious manifestations. Out of this bed developed the “myth of the Lost Cause Myth,” a straw man of sorts, as a way to dismiss or suppress evidence simply by giving it a disparaging category.

The Lost Cause–a term actually coined by a southerner–is well established as myth, and claims that it’s a fabrication are an unfortunate attempt at denying/disparaging the mountains of evidence.

Southerners do have a legitimate perspective of the war, one that should be studied honestly so that it can be understood. It’s the conflation of that perspective with the mythological elements and the denial of inconvenient facts that becomes problematic.

I oppose presentism as a lens for looking at history–but presentism comes in a lot of forms, including the Lost Cause myth.

Chris is entirely correct. The “coiner” of that term was none other than Edward A. Pollard, editor of the Richmond Examiner, who published The Lost Cause: Standard of Southern History of the War of the Confederates in 1867. This phraseology grew into a highly successful public relations campaign to remove the dishonor of a crushing military defeat by recasting the war in a much more favorable light.

And we all know the rest of story: the South was not defeated in a fair fight, but overwhelmed by northern power; slavery was a benevolent institution; secession was a righteous act in traditions of the Founders, blah, blah and blah.

Frankly, I can’t blame Pollard, Jubal Early, and their cronies in the United Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy for concocting their own narrative of the war. A wrecked economy, destroyed infrastructure, and one in four military age men dead, required justification. So, it’s surprising that Southern leaders spun this tall tale to justify secession and the war. And there was no better justification then casting the war as noble struggle for lofty principles against long odds.

Heck, I bought this hokum for many years — it’s a darn good yarn. Unfortunately, when you actually read stuff it doesn’t wash.

The “Lost Cause Myth” is a myth itself. It is a convenient means of dismissing out of hand the Southern side of secession and war, without having to refute the evidence presented. While “Lost Cause” was the title of a Southern book about the war, “Lost Cause Myth” is a fabrication of a modern post 1950’s historiographical method that has as its agenda the conforming of the war, through Marxist style analysis, to a politically motivated agenda that infected an otherwise justified civil rights movement. It is also a means of sanitizing Lincoln’s war that by his own admission and actions had nothing to do with slaves and everything to do with political and economic exploitation of the entire Union.

The plethora of evidence supporting the Southern claim that secession was about seeking independence from a section of the country that had long sought to circumvent the Constitution for its exclusive benefit and to the detriment of the South, is suppressed to and ignored to drive a fabricated “pious cause” narrative. That pious cause narrative began before the war was over, and even Lincoln contradicted his earlier words about what caused the war, by stating in a very vague manner that the war was “somehow about slavery.” As the bodies piled up the North needed a nobler reason for the war instead of “revenue.” Lincoln even sought to absolve himself laid blame for the war at the feet of God.

All along the South had repeated that Northern infidelity to the Constitution was its motivation and independence its cause. Slavery was called the mere “occasion” or “immediate cause” for secession, and invasion the cause for war. Slavery issues represented the North’s most recent and egregious violations of the Constitution but certainly not the only violations, and the South had simply had enough. Especially when Northern abolitionists calling for an irresponsible “immediate” end to slavery, backed by terrorist activity, combined with the election of a sectional President who ran on a platform of high tariffs, and unequal treatment of the South in terms of the commonly owned territories. The latter the South recognized for what it was, which was NOT a moral line in the sand against slavery, but a strategy to prevent Southern allied States being formed in the territories which would block Northern economic ambitions in the Senate. An additional concern for the South had a humanitarian angle. Northern politicians and most abolitionists had long sought to deport all blacks out of the country; or at minimum cut the slaves off from the welfare of the master to “die out” landless, penniless, and unable to compete with whites. Antislavery had an anti-black primary motive. And given the North refused to accept any freed blacks in its States or in the territories, emancipation within the Southern States alone meant a certain humanitarian crises for what amounted to nearly half the Southern population; not to mention the social chaos and disorder that would result from many in the freed population having to resort to mendicancy and crime to survive. There were simply too many slaves to employ profitably, and what was to become of the slaves too old or too young to work who were by law dependent upon the cradle to grave welfare of the master. Southerners defended slavery from irresponsible Northern demands and designs for ending it that held no real concern for the welfare of the slaves. For Southerners, slavery was a safe harbor for the black people Southerners had grown up with from Northern anti-black ambitions. Even Daniel Webster admitted that Southern States were on the cusp of emancipation in the 1830’s until the North started making its unreasonable and exploitative demands.

Post fifties historians have progressively sought to suppress and ignore the mountain of evidence that supports what I have stated above. Those with a bias on the Right, have sought to make the war an example of “American Exceptionalism,” and have wrapped our national identity in a false narrative of a war to free slaves. Those on the Left (the dominant group in academia) have sought to make the war a poster event for equal rights; an oppressor/oppressed narrative that the war was “about slavery” dominates the fabrications of this group. So both the Left and the Right on the political spectrum use the “about slavery” theme but for quite distinct political motivations. But for both historical truth is sacrificed on the alter of political agenda. That slavery ended as an unintended consequence of a war for centralization by which political and economic exploitation could be maintained lends that war NO MORAL MERIT!

My understanding is that there were actually 3-4 separate events, to use a previous commenter’s POV. First, the evacuating Confederates burned munitions trains, which fires then spread to surrounding areas. Then, the Federal efforts can be divided into three “phases:”

1. The kinetic phase—Initially, Sherman told his engineering officer (Poe?) to destroy certain specific buildings and facilities using non-explosive/non-combustive means: knock the building down. The problem was, this was taking too long, so we then had …

2. The authorized fire phase—in which the Federals used fires, but effort was made to prevent the flames from spreading from a target building to non-target buildings, not always successfully. (As any arson investigator will tell you, fire often has a mind of its own.)

Finally, we have …

3. The unauthorized fire phase—as Sherman set out from Atlanta on November 15, numerous stragglers stayed in the city and set a lot of fires, then left (mostly) to catch up with the column. I suspect that a large fraction of the damage to actual private property was the result of this activity.

Of course, if you lost your factory or home, it was little solace which group of Yankees did it, nor did it matter under what authority; it was still gone. As Sherman famously said (sort of), “War is hell.”

A separate comment, and I confess to a degree of laziness on my part here—I can’t find the article in the chaos of my office, but I know I have it.

In the 1950s, a geography professor at the University of Georgia found a map in the University’s collections which was used by one corps of the force that Sherman took to Savannah. (I think it was Fourteenth Corps, but could not swear to it.) The map was very detailed, and was prepared in advance of the March to the Sea. The prof decided it would be an interesting project to document the fate of the many individual buildings marked on this map. Guess what he found? Most of the buildings—which he apparently expected to have been destroyed in the late autumn of 1864—in fact were destroyed long afterward, or were still standing.

The extent of “Sherman’s destruction” is often overstated. I distinctly recall attending a math conference in Alabama in the mid-80s, and chatting with a spouse of one of the local mathematicians at a social event. She said that we should take the time to visit the several well-preserved antebellum mansions in the city (Huntsville), adding the comment that “Sherman for some reason spared them.” I was bold and sassy enough to tell her that Sherman never came near to Huntsville on his March to the Sea. A second, second-hand comment: In Mark Grimsley’s book, “The Hard Hand of War,” he recounts sitting with a local historian in a Georgia town, sharing iced tea on her porch while she waxed eloquent about all the damage Sherman did. Then she asked Mark if he would like to go see some of the many antebellum mansions in the town? Apparently she did not grasp the irony of her offer.

That calls to mind this account: Maj. Henry Hitchcock was newly assigned to Sherman’s army. He rode up to Gen. Sherman as the burning was commencing. Buildings were burning right under the general’s nose. Hitchcock saw Federal soldiers trying to save the courthouse from burning. Thinking this burning was not intended, Maj. Hitchcock remarked “T’will burn down sir.” “Yes,” replied Sherman,”can’t be stopped.”

“Was it your intention?”

“Can’t save it. I’ve seen more of this than you,” said the general.

The general then added that soldiers just do these things. It can’t be stopped. “I say Jeff Davis burnt them.” Hitchcock then apologized, saying he was new. Gen. Sherman replied, “Well, I suppose I’ll have to bear it.”

Sherman’s army had also previously burned the Georgia towns, Rome and Cassville.

Tom

Everyone should read the glorious subreddit ShermanPosting on a regular basis.

How many slave quarters were burned. I bet those slaves got all kind of upset trashing those slave huts. Any book or discussion on upset Slaves and the March that riled them up.

Dr. Mackowski is surprisingly non-informed in stating, “As I recall, Confederates torched the city on their way out of town, doing more damage than Sherman did.” Chris, as a Southerner and an Atlantan, I am offended by your ignorance.

Still fighting the Civil War, 157 years later!

Sherman didn’t fire on Fort Sumter. Start a rebellion and bare the consequences. War is hell and you can not refine it. My southern ancestors were wrong to rebel and we are lucky today that they lost. Once emancipation came their loss was inevitable and we all should be happy that the Union prevailed. Sherman was a complex person and is neither a hero or a villain. He just was one of the winners and on the right side. Lincoln wanted to let the South up easy after their defeat and Sherman did.

As per General Sherman’s Special Field Order Number 120, issued at Kingston, Georgia, November 9, 1864 : “The army will forage liberally on the country during the march.”