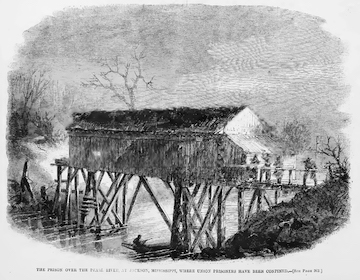

“The prison over the Pearl River at Jackson, Mississippi, where Union prisoners have been confined.”

In researching my forthcoming book on the battle of Jackson, Mississippi—which took place on this date in 1863 as part of Grant’s campaign through Mississippi to take Vicksburg—I stumbled on a little bit of a mystery, although I didn’t know it at the time. My friend Jim Woodrick, a longtime historian for the Mississippi Department of History and Archives, picked up on it as he reviewed my manuscript, and we’ve both been scratching our heads over it since. It deals with a “prison bridge” over the Pearl River.

In researching my forthcoming book on the battle of Jackson, Mississippi—which took place on this date in 1863 as part of Grant’s campaign through Mississippi to take Vicksburg—I stumbled on a little bit of a mystery, although I didn’t know it at the time. My friend Jim Woodrick, a longtime historian for the Mississippi Department of History and Archives, picked up on it as he reviewed my manuscript, and we’ve both been scratching our heads over it since. It deals with a “prison bridge” over the Pearl River.

“Have you ever heard of such a thing?” Jim asked me.

“Aside from the one in Jackson, no,” I replied.

Neither had Jim—nor has he been able to run down any real info on it.

I first stumbled upon the bridge in the June 6, 1863, issue of Harper’s Weekly as I was searching for images I could use in the book. There, I found a sketch captioned “The prison over the Pearl River at Jackson, Mississippi, where Union prisoners have been confined.”

I knew there was a state prison in Jackson, and in my research, I found accounts where Confederate authorities released prisoners before the arrival of the Federal army and the freed convicts promptly set fire to all the prison’s buildings. I’d also found accounts of Federal prisoners being moved through Jackson a few days before the battle but no one who’d actually been kept there.

In the end, I wasn’t sure what to make of the prison bridge, so I skirted around it, although I used the image and captioned it with a good quote from one of Sherman’s men in the aftermath of the battle: “Pearl river bridge having been burnt by the enemy, its abutments were battered down by our artillery,” wrote Charles A. Willison of the 76th Ohio.

But were the Pearl River bridge and the prison bridge the same thing or different? Jim wasn’t sure what to make of it either, particularly because he knew of only one account of the prison bridge. It appeared in the old silver Time-Life book War on the Mississippi:

When Federal troops took Jackson, Mississippi, on May 14, 1863, they liberated fellow soldiers held captive in an unusual Confederate prison—the ruin of a covered bridge on the Pearl River.

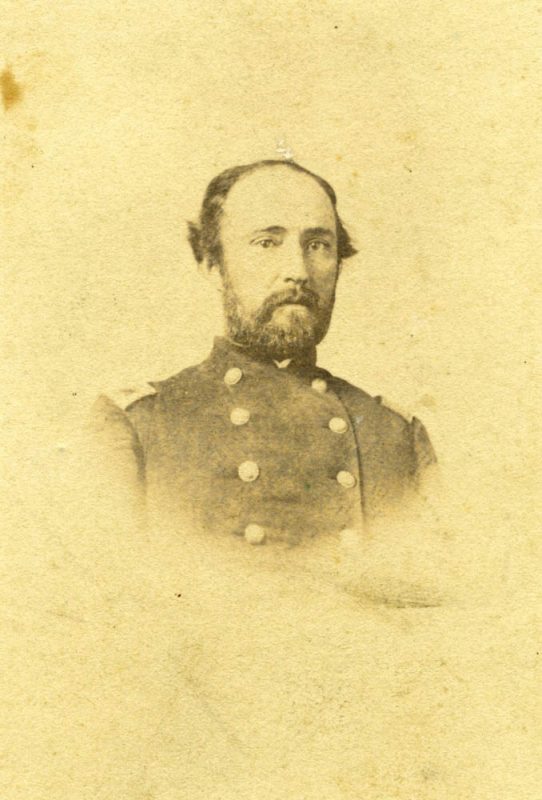

One of the prisoners was Colonel Thomas Clement Fletcher, who drew the sketch in pencil on ruled paper—the only materials available. Colonel Fletcher, commander of the 31st Missouri Wide Awake Zouaves, had been wounded and captured that previous December during General Sherman’s ill-fated offensive at Chickasaw Bluffs.

Conditions for Fletcher, and for the 19 other officers and 380 enlisted men crowded within the rickety structure, were miserable. During the winter of 1862-1863, the prisoners had to endure the cold without benefit of beds or blankets. Afraid that the bridge might burn, the Confederates allowed no fires, or even candles, inside. Exposure and disease caused frequent deaths among the inmates. Almost every day, according to an account published in Harper’s Weekly, two or three were carried out dead, and sometimes the dead lay at the entrance of the bridge unburied for four days.

According the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which has the original sketch by Fletcher, “The artist was confined here by the Confederates, February 1863. Reproduced in wood engraving in Harper’s Weekly, June 6, 1863.”

Fletcher’s account in Harper’s Weekly reads thus:

The Prison at Jackson, Mississippi

We illustrate on page 364 the Prison at Jackson, Mississippi, where many good Union men have been confined since the war broke out, and which lately was destroyed by General Grant. The gentleman who sends us the sketch adds the following account:

“On the 29th December last, at the gallant charge of Blair’s brigade upon the works of the rebels at Chickasaw Bluffs near Vicksburg, Colonel Thomas C. Fletcher, of the Missouri Wide Awake Zouaves, who was wounded and captured by the rebels, was with twenty other officers put in the jail at Vicksburg, where they were kept in the loathsome cells and fed upon the worst fare ever meted out to the vilest criminals for one month. They were then removed to Jackson, Mississippi, and thrust into the old rickety ruin of the bridge which was yet standing above water, the remaining part having fallen down. Here they were kept for another month in the coldest season of the year, without beds or bedding; no fire or lights were allowed them. Three hundred and eighty privates, also prisoners, were put into the bridge with them. Almost every day two or three were carried out dead, and sometimes the dead lay at the entrance of the bridge unburied for four days. The above is a sketch of the bridge made by Colonel Fletcher himself, and we have from his assurances of the correctedness of the statement of a cruelty and barbarity of treatment shown to him while wounded, and to his fellow-prisoners and brother officers, unequaled even by the rebels in the cruelty to our soldiers heretofore while in their hands.”

Colonel Fletcher appends the following certificate:

“The within statement is in all respects correct, but does not fully represent the barbarity of our treatment by the rebels.”

Thomas C. Fletcher,

Colonel, 31st Missouri Volunteers

Annapolis, MD, May 7, 1863 [1]

The author of the Time-Life piece made an assumption that Grant’s arriving army on May 14 freed the Union captives from the prison bridge, as suggested by the Harper’s Weekly article. However, I found no mention of that by anyone. Surely the would have shown up in official reports somewhere. On closer reading, though, Harper’s Weekly only says the bridge “lately was destroyed by General Grant,” with no mention of prisoners. Fletcher’s letter, dated from Annapolis on May 7—a full week before Grant ever arrived in Jackson—suggest the prisoners were released before Grant’s arrival and the Grant did the honors of dispatching the deserted prison.

By May 19, Fletcher had made his way from Annapolis to DeSoto, Missouri, south of St. Louis. Asked to give a speech, Fletcher again described conditions at the prison bridge:

At Jackson they were driven, like so many mules or cattle, into the ruins of an old bridge standing over the Pearl river, without blankets, straw or fire in the most inclement season of the year. They suffered there indescribable torture. A rebel officer, an old friend and clever fellow, brought him a blanket and give him some medicine while he was sick. His fellow prisoners suffered greatly, and several died from the exposure. A Confederate General … had the officers removed from the bridge to a house where they were comparatively comfortable. The men, poor fellows, were left there and died in great numbers.[2]

I did some further digging, which turned up an account from George Ady published in the Chicago Tribune on January 12, 1891, that confirmed the prisoners were exchanged. Ady’s account is interesting enough that I’ll include the bulk of it although he doesn’t get to the prison bridge until the second half:

The writer, who had received a severe wound, was placed in the Jackson (Miss.) hospital for treatment. He says that he had nothing to complain of in his personal experiences there, but he writes the following narrative of the cruel treatment inflicted on the Union prisoners collected there in the winter of 1862-’63. Finally in the spring all of the Union soldiers who remained alive and were able to stand the journey to New Orleans were exchanged. Mr. Ady gives this description of their arrival in New Orleans:

All old soldiers of the war can remember that January, February, March, and April, 1863, were the darkest days of the war. In December, ’62, Sherman had been defeated at Vicksburg and Burnside at Fredericksburg, while Rosecrans’ battle at Stones River was a draw, or at least a victory barren of results. Nothing our side had done had shown any results yet. Grant’s army was in the mud and swamps, on a campaign that was confidently expected by the Confederates to end in failure. Rosecrans was doing nothing apparently at that time, and the Army of the Potomac was stuck in the mud. Traitors at home were making as much capital as possible out of our failures, and urging the abandonment of the war, and the Confederates thought everything was going their way.

At this time, when there seemed nothing to keep up our faith in the ultimate success of the Union, R— and I had it intimated to us that if we would come over to the side of the South and take the oath of allegiance we could both have commissions in the Confederate army and meet with success among new friends. Of course we only laughed at such a proposition. I presume it was meant in earnest, but I do not remember that it made any impression on my mind at the time except that it was offered as a compliment by some who had formed a friendly feeling and some admiration for us. It never struck me at the time that any one would suppose us capable of doing such a thing as turn traitor to our country, but since studying the situation, thinking over the events and feelings of the times, I am led to think it was something of an astonishment to them that we should so lightly decline so much honor.

The Southern people at that time thought their independence already sure, and that everyone would, in a short time, recognize their power and want to be in favor with them.

Bad Quarters and Worse Food.

The winter passed along, slowly enough to us in the hospital, but more slowly still to the poor fellows who were kept prisoners in the old covered bridge over the Pearl River. There were about 350 prisoners in Jackson that winter who had been gathered up from various fights and skirmishes and forwarded there for safe keeping. Soon after R— and I came to Jackson the bridge over Pearl River had broken down under the weight of a battery of artillery, letting men, horses, and guns into the river. Some of the men were badly hurt and were brought to the hospital, and from them and other sources we learned at the time we were moving towards Coffeeville there had been a scare at Jackson, and the military commander had ordered the timbers of the bridge sawed, so that in case of a cavalry dash on the town they would break down and let men and horses into the river. It seemed that in the change of commander, or forces, this had been forgotten, and that the first heavy weight broke down the bridge under their own men.

The bridges was of wood, roofed over with shingles, but with nothing on the sides except the timbers. Into this bridge our prisoners were put, and kept there the balance of the winter. They were more easily guarded than in the empty store buildings, where they had been kept, and then it cost the Confederate Government no rent. Besides the advantages, it kept the men exposed but with little clothing all through the worst part of the winter to the cold, damp, miasmatic atmosphere arising from the sluggish muddy stream so that, in proportion to the ease and cheapness with which there were kept in the bridge, the number to guard and feed was decreased by the ravages of disease. The food, too, was of the poorest quality, very scant, and the medical attendance could scarcely be called by that name. Many of the prisoners were soon sick, and some in their delirium threw themselves into the river and were drowned. I did not know much about this at the time, but learned it afterwards when we were exchanged. None of the sick or wounded were ever brought from the bridge to the hospital. When they were sick, they fared no better, as to quarters, than when well. There were plenty of empty houses at the time in Jackson in which these brave men could have been sheltered.[3]

The rest of Ady’s account talks about the trip to New Orleans for exchange, which he dates as “that 13th day of March, 1863….”

These accounts provide enough clues to follow for additional research. For instance, I suspect the artillery crashing through the bridge, destroying half of it, would be something Jackson’s three newspapers would’ve covered. Perhaps they might have written about the conversion of the bridge ruins into a prison.2n

I haven’t had the chance yet to confirm info on the writer, George Ady, Esq., but the Tribune says his piece was first published in the Denver Commonwealth Magazine. There was a George Ady in Co. G of the 2nd Iowa Cavalry who lived in Denver after the war. His record says he was wounded on December 5, 1862, in Coffeeville, Mississippi, (he mentions in his account that he was there). He was taken as a POW there and later paroled. I’ll have to spend some time trying to follow up.

Along similar lines, nearly every bio of Thomas Fletcher says he was captured at Chickasaw Bayou and taken to Libby Prison, with no mention of his infernal time on Jackson’s prison bridge, despite Fletcher’s published account otherwise. I need to run that down a bit more, too.

In any event, this still doesn’t let either Jim or I know where the prison bridge was located, but now we at least have some breadcrumbs to follow.

[1] Harper’s Weekly, June 6, 1863: https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv7bonn/page/362/mode/2up

[1] Harper’s Weekly, June 6, 1863: https://archive.org/details/harpersweeklyv7bonn/page/362/mode/2up

[2] Daily Missouri Democrat, May 20, 1863, St. Louis, MO—thanks to Kristen Trout for running down this source for me.

[3] “History of Pearl River Bridge from Witness,” Chicago Tribune, January 12, 1891, Chicago, IL: https://chicagotribune.newspapers.com/clip/63805957/history-of-pearl-river-bridge-from/

Thanks for this intriguing report. Having had three relatives captured at Shiloh during the Civil War, and having grown up near the site of Rock Island Prison Camp, I have a particular interest in “the plight of the POW, North and South.” Upon investigation of the Pearl River Prison Bridge, discovered the following:

Prisons in which members of 16th Ohio held: http://www.mkwe.com/home.htm Mike K. Wood site featuring the 16th OVI. Scroll 1/3 way down; under “Images” select “Prisons.” In

“Prisons where members of 16th OVI kept” scroll down to third image: “Pearl River Prison Bridge.” In attached description, “Henry Kiefer” and “Peter Shelly“ link to LETTERS that mention their stay at the Prison Bridge.

As for location of the Prison Bridge, there are four likely sites across the Pearl River: one on the Jackson – Brandon Road (due east of Jackson); and three in vicinity of a pontoon bridge southeast of Jackson. These are included on four “Plates of Jackson Mississippi” found in “Atlas of the Civil War” Plate 37/ 034 (three images) and Plate 39 / 036 (one image.) Plate 37/ 034 Map No.2 also shows a Prison Pen midway between Jackson and the Brandon Road Bridge. https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/atlas-plates-1-60

Cheers

Mike Maxwell

Thanks for this intriguing report. Having three relatives captured at Shiloh during the Civil War, and having grown up near the site of Rock Island Prison Camp, I have a particular interest in “the plight of the POW, North and South.” Upon investigation of the Pearl River Prison Bridge, discovered the following:

Prisons in which members of 16th Ohio held: Mike K. Wood site featuring the 16th OVI. Scroll 1/3 way down; under “Images” select “Prisons.” In “Prisons where members of 16th OVI kept” scroll down to third image: “Pearl River Prison Bridge.” In attached description, “Henry Kiefer” and “Peter Shelly“ link to LETTERS that mention their stay at the Prison Bridge.

As for location of the Prison Bridge, there are five likely sites across the Pearl River: one on the Jackson – Brandon Road (due east of Jackson); and three in vicinity of a pontoon bridge southeast of Jackson. These are included on four “Plates of Jackson Mississippi” found in “Atlas of the Civil War” Plate 37/ 034 (three images) and Plate 39 / 036 (one image.) Plate 37/ 034 Map No.2 also shows a Prison Pen midway between Jackson and the Brandon Road Bridge.

Cheers

Mike Maxwell

Atlas of the Civil War: https://ehistory.osu.edu/books/official-records/atlas-plates-1-60

Very interesting… looking forward to your book too!db

Husband, father, professor, editor, author, speaker, video host. Dude, when do you sleep? ?

Chris, I think I found the location of your bridge – in 1846 the Mississippi Legislature passed an act authorizing the city of Jackson to build a bridge over the Pearl River, “at the most convenient point on said river between the ferry and the Southern boundary of Silas Brown Street.” (Laws of Mississippi, February – March 1846) There were a number of delays, and the bridge was not built until 1849. On December 14, 1849, “The Southron” newspaper reported “The bridge across Pearl River is now completed, and travellers passed over for the first time on Wednesday last.” This bridge, or at least the greater portion of it, collapsed in January 1863 when three Confederate artillery batteries tried to cross – there is a detailed article about this accident in the Vicksburg Daily Whig, January 20, 1863 under the byline “Serious Accident.” I hope this helps, and if you have any questions, feel free to contact me. I am looking forward to reading your book.

Jeff

Fascinating! Please persevere and dig out the facts surrounding the prison bridge.