The 11th Maine at Seven Pines: “Men were being shot on all sides of me”

Along with the Pennsylvanians on their right flank, heavily outnumbered Mainers dueled with Joe Johnston’s advancing Confederates at Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) on Saturday, May 31, 1862. The Yankees paid a terrible price for their heroic stand at a worm fence.

Part of IV Corps (Brig. Gen. Erasmus Keyes), the 3rd Division (Brig. Gen. Silas Casey) picketed a roughly three-mile line from the Williamsburg Stage Road north to the Chickahominy River. Casey had assigned his 1st Brigade (Brig. Gen. Henry M. Naglee) to picket duty.

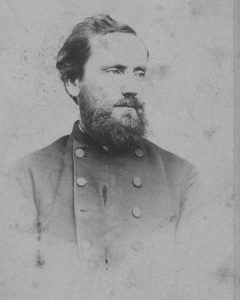

Part of Naglee’s command, the 11th Maine Infantry Regiment (Col. Harris Plaisted) had scattered seven companies along the picket line. Only companies A, C, and F remained in the regiment’s camp.

As general officer of the day, Plaisted checked the picket posts after Saturday’s sunrise. Evidence indicated a strengthening enemy presence in the woods to the west.

Confederate Gen. Joe Johnston planned to strike simultaneously east along the Williamsburg Stage Road and southeast along the Nine Mile Road to outflank the 3rd Division. A serious command error channeled the brigades assigned to both attacks onto the Stage Road instead. The attack fell behind schedule.

Johnston would not be stayed, however. Casey learned between 11 a.m. and noon that Confederates were approaching along the Stage Road. He reinforced his pickets with a Pennsylvania regiment. Two Confederate shells “were [soon] thrown over my camp,” obviously “a serious attack was contemplated,” and he he ordered his camps emptied of every soldier who could carry a rifle.

“The first intuition we had of a battle was some shells thrown in the direction of our camp,” said 2nd Lt. Harrison Hume, the 11th Maine’s acting adjutant. “But in ten minutes after the picket firing commenced, the rebels were right upon us.”

At the 11th Maine’s camp, Maj. Robert F. Campbell told Hume “to form the regiment,” the three companies not already on the picket line. “There is nothing to form,” Hume said.

“Well, form what there is,” Campbell replied.

Hume formed the three companies. From the regimental hospital staggered the sick 1st Lt. William H. H. Rice of Co. G. Urging other sick soldiers to join him, he grabbed a rifle and a cartridge box.

At least a few men followed him, and Campbell brought out 93 men. Riding in from the picket line, Plaisted led his men to a position just north of the Williamsburg Stage Road, between Battery H (1st New York Light Artillery) on the left (south) and the 104th Pennsylvania Infantry on the right (north). The 100th New York Infantry deployed in line south of the Stage Road, across from Battery H.

Confederates attacked “in large force on the center and both wings,” Casey said. Battery H “kept throwing canister into their ranks with great effect,” but Southerners threatened to capture the battery’s four 3-inch Parrotts. Only the cold steel could save those guns.

Around 1 p.m., “Naglee rode up in front of my line amidst a shower of bullets, and ordered me to charge,” Plaisted said. “With the greatest enthusiasm, the order was obeyed.”

As Naglee ordered the 11th Maine — “my little Yankee squad,” he would affectionately call them — to move, Hume led the 93-odd men in three cheers for their general. Moving simultaneously with the 104th Pennsylvania and the 100th New York, the 11th Mainers charged.

Color Sgt. Alexander Katon of Co. B “bore our standard bravely in front of the line,” Plaisted said. When he heard, “Forward to the fence!,” Katon ran “several yards in advance” of the Pennsylvania line some 200-300 yards “across the open space” to a worm fence. Reaching it first, Katon “firmly planted our flag” against it.

He held the flag staff “with the greatest steadiness, amidst such a shower of bullets” that no man could possibly survive, Plaisted believed.

Forming along the fence, the Mainers and Pennsylvanians stood about 50 yards from woods swarming with enemy troops. “We opened fire,” said Plaisted.

The Maine boys fired and fired and fired — and caught hell in the Confederate volleys. Assigned to the color guard, Corp. Willis Maddocks fell dead beside Katon; 2nd Lt. J. William West of Co. C caught a bullet with his heart “and fell near the fence,” Plaisted said

“Men were being shot on all sides of me” as “all around us, the balls were flying like hail,” said Hume, who along with his comrades had “lay down” while “the rebels” were “firing it into us in all directions. “Our men kept firing & we kept telling them to fire low.”

Rice got off 17 shots until wounded in the thigh. Bullets shattered the flag staff held by Katon. Kneeling on the ground, he leaned over Maddocks’ body and held the flag aloft as high as his arms could extend. Enemy bullets punched 11 holes in the flag, but missed Katon altogether.

Plaisted asked Campbell to check the men firing along the battalion’s left flank. Moving from north to south, Campbell leaned over and tapped the back of almost every soldier. “Fire lower, boys, fire lower,” he said.

“His calm, clear commands, as he moved along the line … can never be forgotten by me,” Plaisted said afterwards. “He was unharmed.”

The colonel lost track of time, but the 11th Maine and 104th Pennsylvania could not have fought for long. With the Pennsylvanians finally falling back and “two-thirds of my commissioned officers and one half of my little battalion … either killed or wounded,” Plaisted “reluctantly … gave the order, ‘Retreat.’”

“Had we stood there twenty minutes longer, we should have all died,” Hume said. His comrades retreated east with “the balls falling like hail,” the Mainers “being under a cross fire. Many of our men were wounded in retreating.”

Plaisted lost 52 men (six dead, 39 wounded, and seven missing) of the 93 soldiers he brought to the fight.1

1 Adapted from Brian F. Swartz, Maine at War, Vol. 1: Bladensburg to Sharpsburg (Brewer, ME, 2019), 177-186

A tough and brutal open field fight, like so many before they learned the craft better.