The fall of Vicksburg: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion

On July 4, 1863, Major General U.S. Grant’s army captured Vicksburg, Mississippi. This campaign often gets hastily passed over in history conversations. Gettysburg and Fourth festivities take precedent. I’m at fault for neglecting this event as well. Still, the fall of this small, quiet town played a pivotal role in the destruction of the Confederacy some twenty-one months later.[1] Why was Vicksburg so important? Think of the town like the hub of a wagon wheel, that’s how significant its location was. It occupied the first high ground south of Memphis, overlooking the Mississippi River—the most important highway in the nation. On land, two railroad lines traversed through the region. One line ran east and connected with other roads “leading to all points of the Southern States.”[2] The other railroad line started from the opposite side of the river and extended “west as far as Shreveport, Louisiana.”[3]

Vicksburg was the last stronghold guarding the Mississippi River. The side that held this town thus commanded the tons of supplies moving to-and-fro. The Confederacy also could only challenge the Federal Navy’s control of the river by means of the land-based artillery at Vicksburg. Furthermore, Port Hudson, Louisiana and other forts south of the city would become untenable if Vicksburg fell. By 1863, Vicksburg was the last remaining junction that connected the communication lines across the breadth of the Confederacy. Arkansas, Texas and Louisiana lay to the west. Mississippi, Alabama, Tennessee, Georgia, Florida, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia lay to the east.[4]

From the get go, President Abraham Lincoln understood the strategic situation, aka big picture. He aptly referred to the mighty Mississippi River back in 1862 as “the backbone of the Rebellion [and the] key to the whole situation.” As long as the Confederates held it, they could “obtain supplies of all kinds, and it [was] a barrier against our forces.”[5] Taking the strongholds along the Mississippi had to be done in order to bring all the southern states back into the union.

The Confederacy, on the other hand, had General Robert E. Lee. He looked at the situation through a narrow lens. On April 10, 1862, he wrote to Major General John C. Pemberton, commanding general in the western theater: “If [the] Mississippi Valley [was] lost [the] Atlantic States [would] be ruined.”[6] Herein lay the problem for the Confederacy. Lee only had one strategy: win the war in Virginia.

Lee saw the Vicksburg and Mississippi Valley dilemma as “a question between Virginia and the Mississippi.”[7] This was a crucial point. Would the entire Confederacy collapse if Richmond were taken, or would it fail if the government moved somewhere else, such as Atlanta? Lee wouldn’t consider these and many more questions.[8] So, come early spring 1863, he refused to transfer any of his divisions out west And there was still time to at least try and relieve pressure out west but no relief came.[9]

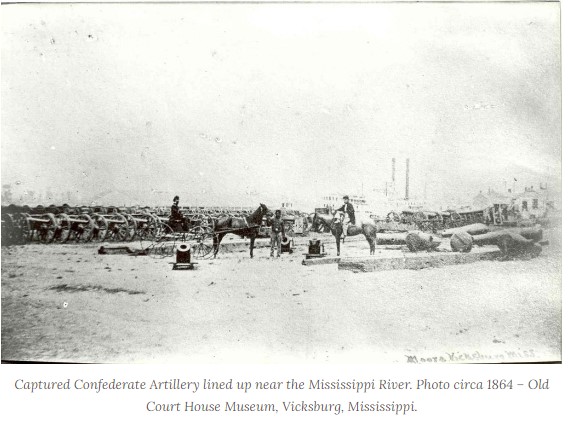

Instead, Grant’s army gobbled up the Mississippi Valley. The entire Vicksburg Campaign spanned November 2, 1862–July 4, 1863.[10] It was exceptionally brutal. Civilians were trapped and starving in the city; much of Vicksburg lay in ruins. Finally after nine months, the Confederates surrendered. The Union forces captured a foundry, 60,000 rifled muskets, 172 cannon, a substantial amount of ammunition, and 31,600 Confederate soldiers.[11]

The surrender of Vicksburg was like a domino effect. Union troops shortly thereafter walked into an abandoned Jackson, Mississippi; most of the state of Mississippi was now in Union hands.[12] And six days after Vicksburg fell, the Confederate garrison at Port Hudson surrendered.[13] The entire Mississippi River and Valley was gone. The Union armies and navy had severed the “backbone of the Rebellion”. Louisiana, Texas, and Arkansas lay isolated, while the southern states to the east were exposed to invasion from the north and west. It was just a matter of time before the Confederacy capitulated.[14]

[1] Many thanks to Bill Jayne for his editorial comments. Bill is a life long student of military history. He is president of the Cape Fear Civil War Roundtable. He served in the 27th Marines at Khe Sanh. After Vietnam, he attended Berkley where he earned an English degree.

[2] U. S. Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol. 1, 250.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] David Porter, “The Opening of the Lower Mississippi,” Battles and Leaders, vol. 2, 24. For more on Vicksburg, see Shea and Winshel, Vicksburg is the Key, and Terrence J. Winshel, Triumph and Defeat: The Vicksburg Campaign (New York: Savas Beatie, 2004), and Dr. C. Gabel, Staff Ride Handbook for the Vicksburg Campaign, December 1862–July 1863 (Pickle Partners Publishing, ebook).

[6] R. E. Lee to Major General John C. Pemberton, Richmond, VA, April 10, 1862, O.R., Ser. 1, vol. 6, 432.

[7] R. E. Lee to James Seddon, Fredericksburg, May 10, 1863, O.R. Ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 2, 790.

[8] Edward Porter Alexander, Fighting for the Confederacy, criticizes Lee several times for his Virginia-centric view of the strategic problem. The 1907 edition of this book is on google books for free.

[9] On March 11, Lee attended a council of war in Richmond to discuss the strategic situation. For meeting and date, see Archer Jones, “The Gettysburg Decision,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 68, no. 3 (July 1960): 332. On April 6, Secretary of War Seddon wrote to Lee and again asked him if he could send just two brigades to Bragg. See James Seddon to R. E. Lee, Richmond, VA, April 6, 1863, O.R., Ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 2, 708–09. Then, on April 14, Adjutant and Inspector Samuel Cooper, on behalf of President Davis, beseeched Lee to relinquish two divisions for middle Tennessee. See Adjutant and Inspector General S. Cooper, Richmond, VA, April 14, 1863, O.R., Ser. 1, vol. 25, pt. 2, 720. Davis had seen how dire the situation was in Tennessee and Mississippi as he had traveled to these states in December 1862, see Joseph Johnston, “Jefferson Davis and the Mississippi Campaign,” Battles and Leaders, vol. 3, 474–75.

[10] Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol. 1, 250.

[11] Battles and Leaders, vol. 3, 537.

[12] General Johnston had two choices at Jackson, Mississippi: he could prepare for a siege that would trap his army or evacuate his army, see J. E. Johnston to Davis, Jackson, July 16, 1863, and Brandon, July 16, 1863, found in Johnston, Narrative, 567. For Vicksburg, see O.R., Ser. 1, vol. 24, pts., 1–3 and vol. 26 pts., 1–2, and U. S. Grant, Personal Memoirs, vol. 1, 422–570. For quote, see David Porter, “The Opening of the Lower Mississippi,” Battles and Leaders, vol. 2, 24.

[13] The South lost another 5,500 soldiers as prisoners, including one major general and one brigadier general, “20 pieces of heavy artillery, 5 complete batteries, numbering 31 pieces of field artillery, a good supply of projectiles for small-arms, [and] 150,000 rounds of small-arms ammunition.” See Major General Nathaniel P. Banks to Major General Henry W. Halleck, General-in-Chief, Headquarters, Port Hudson, LA, July 10, 1863, O.R., Ser. 1, vol. 26, pt. 1, 55.

[14] Illustration 1: Strategic Significance of Vicksburg, map taken from R. E. Lee’s Grand Strategy and Leadership by JoAnna McDonald. Savas and Beatie Publications, El Dorado Hills, CA. Date: TBD. Illustration 2: Steamboat, https://shiphistory.org/2021/02/26/steamboats-enslavement-and-freedom/. Illustration 3: Mississippi: Backbone of the Rebellion, https://www.nps.gov/articles/the-siege-of-port-hudson-forty-days-and-nights-in-the-wilderness-of-death-teaching-with-historic-places.htm. Illustration 4: Vicksburg, http://npshistory.com/publications/civil_war_series/24/sec9.htm. Illustration 5: Captured cannon, https://mississippiconfederates.wordpress.com/2014/05/14/artillery-during-the-siege-of-vicksburg.

Thanks for the kind words, JoAnna but I have to make a correction. I served in the 26th Marine Regiment at Khe Sanh. The 27th Marines had a short tour in Vietnam but never made it to Khe Sanh. All three battalions of the 26th Marines were at Khe Sanh during the 1968 siege, along with the 1st Battalion of the 9th Marines.

Thanks Bill! Sorry about that. Semper Fi

Thank you JoAnna for the excellent presentation on the significance of Vicksburg! Many of us feel the loss of Vicksburg was more important for the Confederacy because an Army surrendered.

We look forward to your future presentations!

Thank you for initiating this discussion of the “Union push for Vicksburg,” which was set in motion by the U.S. Navy in May 1862; re-attempted by the Navy in June 1862 (and stymied by surprise appearance of CSS Arkansas); resulted in Failure under the Army’s William Tecumseh Sherman at Chickasaw Bluff during the NOV/December 1862 campaign; resulted in “political redirection” of Major General John McClernand to Arkansas Post (followed by extensive efforts to dig a canal, by-passing Vicksburg); and ultimately involved Ulysses S. Grant in non-stop exertions, directing approach from the rear, Naval bombardment from the front, and finally incorporating sapping and mining, resulting in success… on 4 July 1863.

I’m a little late on this but thought some clarification would be useful. The Arkansas didn’t stop Farragut from taking Vicksburg in summer ’62; Halleck did. Farragut had an armada of his deep-water Gulf Blockading Squadron and the Mississippi River Squadron along with Porter’s mortar boats. Lincoln and Welles ordered him up the Mississippi after New Orleans to take Vicksburg, but he couldn’t do it alone from the water. The Admiral begged the theater commander to send troops after Shiloh and Corinth. Grant and Sherman would have jumped at the chance. But Halleck had no interest, and the opportunity was lost much to the dismay of Lincoln.

Dwight Hughes, you are correct in implying that, “Neither David G. Farragut nor Benjamin Butler were responsible for the ultimate failure of the 1862 New Orleans Campaign, that failure due to lack of timely arrival with sufficient force at Confederate Vicksburg.” And the culprit is not David D. Porter or Henry Halleck, either. The blame rests elsewhere…

Cheers

Mike Maxwell

i wish to point out that the U.S. army occupied Jackson, Mississippi, before (not after) the surrender of Vicksburg. Also, that state continued to furnish food for Confederate forces until the end of the war since the Mobile & Ohio RR remained in Confederate hands. The Confederates captured at both Vicksburg and Arkansas Post were paroled and most were back under arms by September when they fought at Chickamauga.

Rosecrans’s victory in the Tullahoma Campaign, and his holding out at Chattanooga until rescued, shifted the focus of the war in the west from the Mississippi to Chattanooga–Atlanta. Vicksburg became a backwater. The real importance of its capture was opening the route to market for Midwestern farmers.

Your points are well taken on all but Jackson. On that one, you and Joanna are both right. Grant’s army occupied Jackson in May 1863 for a time, then gave it up to the Confederates after destroying military stores. In mid-July the U.S. Army reoccupied Jackson and held it for the rest of the war.

Robert E. Lee had little to do with the story of Vicksburg, as he was not in command of any western forces at that time. He did oppose the transfer of units from the East. But I think he was correct in doing so as the men and units on hand had successfully resisted several attempts by Grant already, and could have again had a more competent commander been on the scene.