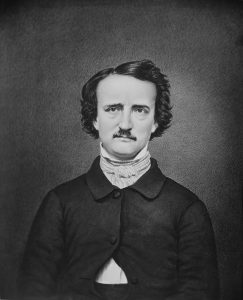

Amasa Converse, the minister who fled South after the Lincoln administration suppressed his Philadelphia newspaper (cameo appearance by Edgar Allan Poe), Part One

Rev. Amasa Converse, during his lifetime, managed to move from the North to the South, back to the North, and then – quite hurriedly, during the Civil War – back South again. He found time during all this to officiate at Edgar Allan Poe’s wedding, a role which gives him some fame among Poe aficionados. Converse should also be better known among Civil War buffs – his newspaper was shut down by the government in the North, only to emerge phoenix-like as a Confederate paper in the South. During all this, he thought he was pursuing his duties as a Christian minister.

Born in 1795, Converse grew up on a New Hampshire farm with six brothers and three sisters. New Hampshire farming was not exactly light work, so industriousness was inculcated in him along with the religion of his pious parents.[1]

Converse’s father had enough money to offer a hundred dollars each to his sons out of his estate. Young Amasa made a deal – he would give up his right to the money, and in exchange he would be able to work for himself. He bought some wild land and labored indefatigably to clear the New Hampshire soil and make the land into a farm.[2]

Amasa wanted an education, and to get one, he supported himself with his farming and by teaching school himself. This allowed him to pay tuition at the different schools he went to. Going to school entailed walking many miles in the snow, which may have had relevance to his later health problems.[3]

During the time of his early education, Converse had a religious conversion. As he later recounted, despite his parents’ teachings he had neglected God and even fallen into skepticism. Under the influence of a pious man, he decided to stop “living like an atheist, without God and without hope in the world.” He was at the Phillip’s Academy prep school in Massachusetts when, tormented by religious anxieties, he received a vision of happiness which though it only lasted one or two hours, inspired him to keep going and finally accept membership in a Congregationalist church. Since the New England Congregationalists were then associated with the Presbyterians elsewhere in the country, he had a Presbyterian connection available if he left New England.[4]

His piety impressed the young ladies at a female school where he taught, so that, he noted proudly, on their own initiative they all turned down invitations to a New Year’s ball. Converse doesn’t give details of the kind of non-pious activities his charges were shunning.[5]

After Phillip’s Academy it was on to Dartmouth, and then to the Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey, where Converse pursued his studies despite failing health. His mentor, Dr. Archibald Alexander, persuaded him to go to a warmer climate where, with exercise, he might get his health back. Dr. Alexander was a founder of the seminary, but he was a doctor of divinity, not a medical doctor. Still, Converse (soon to be a Doctor of Divinity himself) decided to accept the health advice of Dr. Alexander.[6]

So in 1825, Converse moved to Virginia to recover his health and work as a Presbyterian preacher. He had plenty of opportunity to exercise himself through horseback riding, riding through the rural districts to which he was assigned, in the countryside in Southside Virginia (a large area south of Richmond). Once again, he helped support himself through teaching – since congregants in that part of Virginia were not sufficiently generous to provide a living wage to preachers. Converse ran a school where, according to the later notes of amateur historian Walter A. Watson, he could be cruel. Watson reports that a boy who was enrolled in the school, the son of a wealthy planter, offended Converse in some way, and Converse pulled the boy’s ears, injuring him. The father pulled the boy out of the school, and the boy later died, though Watson does not specifically claim a cause-effect relationship. This sort of dangerous discipline – hardly unknown to educators then – could be compared either to a Three Stooges stunt or to something out of Poe, depending on whether it was connected to the boy’s early death.[7]

Converse was ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1826, though he was not content with his life as a preacher. The indifference of many in the community, and his bad speaking voice, may have affected this discontent. He took on a role in 1827 which turned out to be his lifetime’s vocation: he became a religious editor. He got the editorship of two Richmond periodicals, the Family Visitor and the Literary and Evangelical Magazine. Both periodicals were in a bad financial situation, but Converse turned things around – closing the magazine to focus on the Family Visitor newspaper. He dealt with the paper’s debts and boosted the circulation. By this time the paper had a new name – the Southern Religious Telegraph – and it was doing quite a bit better than before.[8]

During Converse’s time in Virginia he undertook a re-examination of the issue of slavery. As a youth in New England and the North, he had been vehemently antislavery, even defending a slave’s right to kill his master in order to escape from bondage. With further study of the Biblical basis of slavery – probably influenced by his “going native” while residing in a slaveholding community – Converse changed his mind and decided that slavery was OK, or at least not wrong as such.[9]

Converse kept up some conventional ministerial activities while running his paper. On May 16, 1836, probably in his own home, Converse presided over the marriage of Edgar Allan Poe to Poe’s cousin Virginia, who was only thirteen years old. The law of Virginia (the state) did not ban cousin-marriage, nor did it ban girls as young as Virginia (the bride) from being married. But there would have been more paperwork involved if Virginia’s true age were known, which may be why Poe represented his bride’s age as 21. Converse probably accepted these claims at face value. Given the loving relationship between Edgar Allan Poe and Virginia Clemm Poe during their years together, maybe this marriage was the best service any editor ever did for Poe.[10]

One responsibility of Presbyterian ministers is to attend presbyteries, meetings to formulate church policy. In the local presbyteries, Converse was a leader in pushing for proper, pious observance of Sunday. Elite Presbyterians were too much given to worldly activities on the Lord’s day. With Converse’s backing, the local presbytery called on Presbyterians to avoid travel, “unnecessary labors and worldly conversation” on the Lord’s Day.[11] (Were slaves to be afforded the same respite from worldly work?)

Around the time of Poe’s marriage in 1836, a dispute was brewing within the Presbyterian Church. The slavery issue was lurking in the background and may have exacerbated the conflict, but strictly speaking, the dispute was over methods of evangelization and missionary work. The quarrel culminated in 1837 with the majority faction exscinding (cutting off from the denomination) a large minority. Converse sided with the minority, not strictly on doctrinal grounds but based on Presbyterian constitutional law (what theologians call ecclesiology). The majority’s actions were arbitrary and contrary to church law, in Converse’s eyes, so he joined the minority – which was called the New School denomination.[12]

The majority of Presbyterians in the South joined the rival Old School denomination, generally because the New School contained a substantial New England component, and the New Englanders were more likely than other Presbyterians to be antislavery. Converse no longer sympathized with his native New England on the slavery issue – but he was on the New England side in the Church split. Because of the controversy, the Southern Religious Telegraph’s circulation dropped.[13]

Converse listened with interest to a proposal from eminent New School figures that he take over a troubled Philadelphia religious paper and turn it around, just as he’d done in Richmond (before the schism cut into sales). Converse and the New Schoolers reached an agreement, and in 1839 Converse moved his family and newspaper equipment to the City of Brotherly Love. As he had with the Richmond paper, Converse turned the Philadelphia paper around. He renamed it the Christian Observer, improved its circulation and finances, and operated it on behalf of the New School denomination – or at least according to his own view of what the New School Presbyterians should stand for.[14]

While he protested that he did not wish to spread proslavery ideas, Converse did say he wanted to keep slavery out of the discussions of the New School denomination. Converse used the pages of the Christian Observer to urge the New Schoolers to stay away from the topic of slavery, and at first they did, rejecting antislavery petitions from activist members – or as Converse saw them, fanatics and agitators, afflicted with “monomania.”[15]

————

[Note – An earlier version of this article used to appear (behind a paywall) on my Substack account.]

[1] Amasa Converse, “Autobiography of the Rev. Amasa Converse,” Part 1 [including editorial introduction], Journal of Presbyterian History, Vol. 43, No. 3 (September 1965), pp.197-218, at 197; “The Rev. A. Converse, D. D.,” The Christian Observer, 51.51 (18 December 1872): 1.1-5, reprinted in “Death of the Rev. Dr. Amasa Converse, 9 December, 1872), http://christianobserver.org/death-of-the-rev-dr-amasa-converse-9-december-1872/.

[2] Autobiography, Part 1, 198; “The Rev. A. Converse, D. D.”

[3] Autobiography, Part 1, 198-99; “The Rev. A. Converse, D. D.”

[4] “The Rev. A. Converse, D. D.”

[5] Autobiography, Part 1, 200.

[6] Autobiography, Part 1, 202; “Incarnation, Archibald Alexander,” Presbyterians of the Past, https://www.presbyteriansofthepast.com/2019/12/21/incarnation-archibald-alexander/.

[7] Autobiography, Part 1, 202-3; Walter A. Watson, Notes on Southside Virginia. David Bottom (Superintendent of Public Printing), 1925. In Bulletin of the Virginia State Library, September 1925, 182.

[8] Autobiography, Part 1, 204-6.

[9] Autobiography, Part 1, 214.

[10] Paul Collins, Edgar Allan Poe: The Fever Called Living (Boston: New Harvest, 2014), 31-33; James M. Hutchinson, Poe (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2005), 55-56. There are two competing accounts of where the wedding was held. An account by one James Whitty puts the marriage at the boarding house where Poe was staying. Poe Museum, “Today Marks Edgar Poe’s 177th Wedding Anniversary,” May 16, 2013, https://poemuseum.org/today-marks-edgar-poes-177th-wedding-anniversary/.

Whitty’s overall credibility has been questioned. “Marginalia: Special J. H. Whitty Memorial Edition,” https://worldofpoe.blogspot.com/2011/05/marginalia-special-jh-whitty-memorial.html.

The Poe Museum also quotes the conflicting account of Francis Bartlett Converse, Amasa’s son, who wrote in 1904 that Poe “was married by my father…in my father’s parlor…at the Southeast corner of Main and Eighth Streets, Richmond…Edgar Allan Poe came to the house, and the wedding was performed in the parlor, my father standing, according to the impressions which I have received, near the mantel piece and Edgar Allan Poe and his bride coming in at the front. There were very few persons present at the wedding, my mother and the members of the family, and perhaps one or two more companions, which they brought with them.”

I’ve followed Francis Converse’s account since Francis Converse doesn’t seem to have the same credibility problems as Whitty.

As to Poe’s religion, the various pieces of evidence are investigated in “Edgar Allan Poe and Religion,” Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, January 14, 2014, https://www.eapoe.org/geninfo/poerelig.htm.

[11] Forrest L. Marion, “‘All That Is Pure in Religion and Valuable in Society’: Presbyterians, the Virginia Society, and the Sabbath, 1830-1836,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 2001, Vol. 109, No. 2 (2001), pp.187-218, at 209.

[12] Autobiography, Part 1, 209-11. For the schism, see James H. Moorhead, “The ‘Restless Spirit of Radicalism,’ Old School Fears and the Schism of 1837,” The Journal of Presbyterian History, Vol. 78, No. 1 (Spring 2000), 19-33; C. Bruce Staiger, “Abolitionism and the Presbyterian Schism of 1837-1838,” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 36, No. 3 (December, 1949), pp. 391-415.

[13] Autobiography, Part 1, 211; Elwyn A. Smith, “The Role of the South in the Presbyterian Schism of 1837-1838,” Church History, Vol. 29, No. 1 (March, 1960), pp. 44-63.

[14] Autobiography, Part 1, 212-13.

[15] Autobiography, Part 1, 216-18.