Barlow and Gordon at Antietam

Stand aside Gettysburg. It’s the middle of September, and you’re not the only place with a Barlow-Gordon story. (And yes, I see you, Spotsylvania, but you’ll have to wait your turn.)

In case you haven’t heard of the Barlow-Gordon story (a.k.a. controversy) from Gettysburg, here’s the short version. Union General Francis C. Barlow was badly wounded and left on the field during the afternoon of July 1, 1863, as his division of the XI Corps retreated. Confederate General John B. Gordon found Barlow and had some sort of rather lengthy interaction with him. They parted, and Gordon claimed they never knew that the other had survived the battle/the war until they met post-war in a grand reconciliation story. (I have doubts and have been looking at it for a couple of years.)

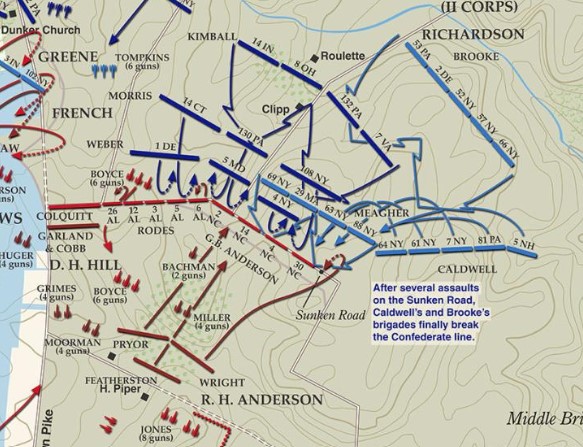

Now, it’s Antietam’s turn! Because the September 17, 1862 battle has its own Barlow-Gordon story. Perhaps not as dramatic in the legendary sense as Gettysburg, but perhaps more important in the military sense. Gordon was one of the colonels battling to hold the infamous Sunken Road while Barlow was the colonel who led the militarily successful flanking movement on the road which turned it into the Bloody Lane.

Colonel John B. Gordon commanded the 6th Alabama, part of Rodes’s brigade in D.H. Hill’s division, which positioned approximately at the “turn” in the Sunken Road. (See map) In his post war reminiscences, Gordon wrote his memories of the battle of Antietam:

“The day was clear and beautiful, with scarcely a cloud in the sky. The men in blue filed down the opposite slope, crossed the little stream (Antietam), and formed in my front, an assaulting column four lines deep…. It was a thrilling spectacle…. On every preceding field where I had been engaged it had been my fortune to lead or direct charges, and not to receive them; or else to more as the tides of battle swayed in the one direction or the other. Now my duty was to move neither to the front nor to the rear, but to stand fast, holding that centre under whatever pressure and against any odds.

“Every act and movement of the Union commander in my front clearly indicated his purpose to discard bullets and depend upon bayonets. He essayed to break through Lee’s centre by the crushing weight and momentum of his solid column. It was my business to prevent this….”

Gordon had been commanding the 6th Alabama since May 1862, but he had been an officer in the regiment since its formation 1861. At Antietam, he ordered the soldiers to hold their fire. He believed that by letting the attacking Union troops get close to the Sunken Road then opening a powerful, close-range volley, he would be able to stop and drive back the charge. When “the front rank was within a few rods of where I stood…it would not do to wait another second, and with all my lung power I shouted ‘Fire!’”

As Gordon had expected, the close-range fire was devastating. He later remembered the entire front line going down before his regiment’s volley. Along the Sunken Road, other Confederate regiments decimated the foes to their fronts as well.

But the Union attacks continued. More brigades from the II Corps were sent into the storm to pierce the Sunken Road. The famed Irish Brigade rushed forward, but could not reach the position. The Confederates took comfort in the slight protection that the Sunken Road offered. Still, some Rebels were wounded, including Colonel Gordon.

Gordon was wounded five times during the combat at the Sunken Road. His final injury—a head wound—felled him and might have killed him by drowning him in pooling blood as he lay face downward. A previously created bullet hole in the cap drain the blood, and Gordon believed that saved his life. Understandably, Gordon was imprecise with his estimates of time, but it seems most likely he was wounded before the 61st and 64th New York turned the flank of the Sunken Road.

Out in the rolling landscape in front of the Sunken Road, Union charges collapsed and retreated, leaving dead and wounded carpeting the fields. Still, the officers ordered more frontal assaults. Caldwell’s brigade turned toward the deadly field. Two New York regiments—the 61st and the 64th—positioned on the left flank of the brigade as it literally swung around to face the Sunken Road. However, these regiments’ commander, Colonel Francis C. Barlow, spotted an opportunity.

Barlow had volunteered in the earliest days of the Civil War, and later in 1861 had joined, drilled, and prepared the 61st New York Infantry Regiment. The Peninsula Campaign had convinced him that action would secure victories. On September 17, Barlow saw an opportunity for innovative, yet still “textbook” military action. What if a regiment could get on the flank of the Sunken Road and enfilade it? Clearly, the frontal assault concept wasn’t working. Barlow took his combined command and slipped toward the Confederate’s right flank.

In his official report, Barlow recorded:

“The portion of the enemy’s line which was not broken, then remained lying in a deep road, well protected from a fire in their front. Our position giving us peculiar advantages for attack in flank this part of the enemy’s line, my regiments advanced and obtained an enflading fire upon the enemy in the aforesaid road. Seeing the uselessness of further resistance, the enemy in accordance with our demands threw down their arms, came in in large numbers and surrendered. Upwards of three hundred prisoners thus taken by my regiments were sent to the rear with a guard of my regiment…. On this occasion, my own regiment, the Sixty-first New York, took two o the enemy’s battle flags… A third flag was captured by the Sixty-fourth New York, which was lost by the subsequent shooting of the captor when away from his regiment.”

After temporarily securing the Sunken Road, Barlow turned his attention toward the Piper Farm, ordering a pursuing advance into the cornfield behind the road. Barlow was wounded in that action and taken unconscious from the field.

There’s no feel-good reconciliation story of Gordon and Barlow meeting in a field hospital at Antietam. And there’s no way to say that they came against each other directly—regiment vs. regiment—at this battle either. However, it is accurate to say that Colonel Gordon was one of the defenders of the Sunken Road, and Colonel Barlow led the flanking attack that “broke” that position. They were in relatively same place, at the same time. They were both wounded at Antietam, but both would return to command—and with promotions—and they would fight each other more directly on other battlefields in Pennsylvania and Virginia.

Sources:

Francis C. Barlow, edited by Christian G. Samito, “Fear was not in him”: The Civil War Letters of Major General Francis C. Barlow (New York: Fordham University Press, 2004). Pages 116-117.

Charles A. Fuller, Personal Recollections of the War of 1861.

John B. Gordon, Reminiscences of the Civil War (1903). Pages 83-90. Accessed via Google Books.

This post is wonderfully written and most engaging. Having been trained in fire and flank tactics in the late 1960’s, I can sense the thrill Barlow must have felt when he saw, ordered and executed the enfilading action. I am not sure the American Battlefield Trust maps, always top-notch, really show the details of Barlow’s action as he describes it.

What are your thoughts on the Gordon-Barlow story? I am in the process of writing my own blog post on the subject. Through my in-depth research on Barlow I have come to my own opinion but interested to hear how you interpret the story.