Things I have learned on the way to Atlanta – Johnston as Executioner

Last week’s post, about Yankee pickets firing snow bombs at each other, made me laugh. Soldier life, however, was rarely so amusing.

From my forthcoming volume on the first part of the Atlanta Campaign, to be published by Savas Beatie, LLC:

The postwar view of Joseph Johnston, especially in the former Confederacy, was largely positive. With a view heavily tinted by extra-thick rose-colored glasses, former soldiers of the Army of Tennessee recalled Johnston as the man who rebuilt the army after Bragg’s disastrous defeat (largely true) and who understood the men in the ranks far better than either Braxton Bragg or John Bell Hood, who took over in July of 1864.

The postwar view of Joseph Johnston, especially in the former Confederacy, was largely positive. With a view heavily tinted by extra-thick rose-colored glasses, former soldiers of the Army of Tennessee recalled Johnston as the man who rebuilt the army after Bragg’s disastrous defeat (largely true) and who understood the men in the ranks far better than either Braxton Bragg or John Bell Hood, who took over in July of 1864.

However, morale remained a problem. In January of 1864, the Army of the Cumberland’s Provost Marshal processed 625 prisoners of war, 635 Rebel deserters, and administered 1005 oaths of allegiance or amnesty. February was a busy month, with 662 prisoners, 897 deserters, and 806 oaths. In March, the numbers were 145 prisoners, 653 deserters, and 925 oaths administered. April produced 264 captures, 363 deserters, and 903 oaths. Even in July, with active operations underway, the Federals captured 3,200 Confederates, thanks to the heavy combats of that month, but also took in another 702 deserters. Losses for the first four months of the year alone, before heavy fighting erupted, amounted to 4,244 officers and men, or just over 1,000 a month—the equivalent of a small brigade every 30 days. And while not all the captures could be considered voluntary, enough were to be worrisome. And these numbers included only those Confederates who ended up in Union hands—many others simply left the army without passing through the Federal provost office.[1]

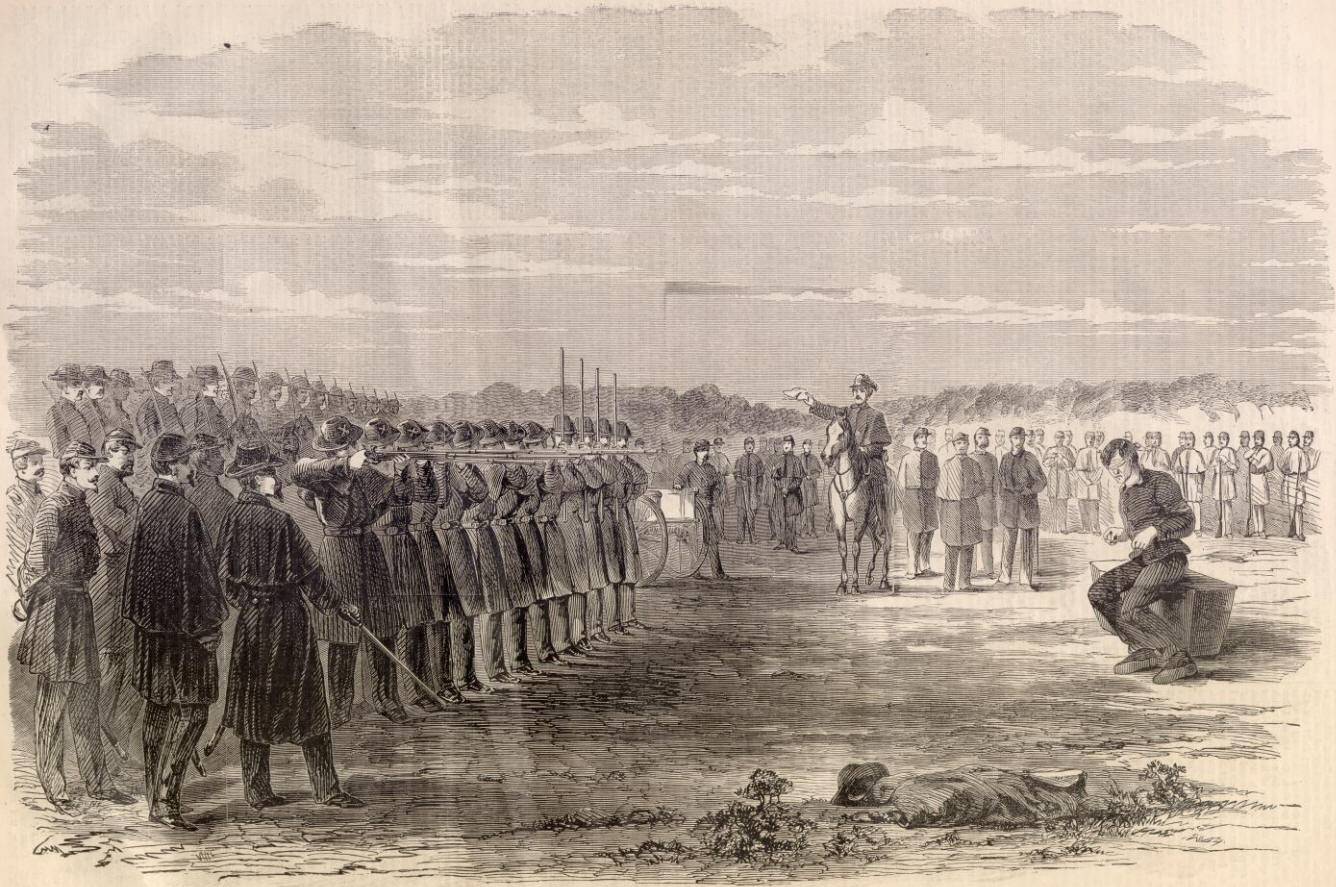

To curb this problem, Johnston turned to a number of carrots—furloughs, improved rations, and the like—but also unsparingly employed the stick. Executions, to be precise: Johnston signed the death warrants of far more deserters in just four months than Bragg ever did. Historian Larry Daniel identified at least forty executions between January 2nd and May 5th. Fourteen men were shot on May 4 alone, equaling the number Braxton Bragg put to death during that general’s entire tenure in command—a span of more than eighteen months.[2]

The mass executions of May 4th and 5th shocked the army. A total of twenty-one deserters were slated to be sht, including a man each from the 58th Alabama, 30th Georgia, 40th Georgia, and 63rd Virginia; two each from the 42nd Georgia and 60th North Carolina; and no less than thirteen soldiers belonging to the 58th North Carolina. As noted fourteen of them fell on the 4th. The number would have been sixteen, except that one of the 58th North Carolinians and one young Georgian (said to be “a half-witted fellow, almost devoid of reason”) were reprieved. Capt. Ellis Claiborne, then serving on brigade commander Alexander W. Reynolds’s staff, described it as “the most terrible scene I ever witnessed. Eighteen men were detailed as the firing squad for each of the condemned, with one quarter of each squad’s muskets randomly loaded with blanks by the staff, then the whole party solemnly marched to the killing ground.” Fourteen posts had been erected, coffins laid out, and the division was formed to witness the event. The condemned were blindfolded, and then the executioners “form[ed] in line ten paces in front of the” prisoners. The process did not go smoothly. “Only eight were killed in the first volley,” noted Capt. Phifer Erwin of the 60th North Carolina, “though the other six were badly or mortally wounded. . . . Those who were not instantly killed were shot again by the guard.” After the division left the field, “the bodies of the executed men [were] . . . buried in one common grave with neither stone nor board to mark the spot.”[3]

On May 10th 60th Virginia Pvt. William Cooper contrived to fall into Union hands. Though listed as “captured” on the regimental muster rolls, Cooper made it very clear he was leaving the Rebel army voluntarily. In a sworn statement he insisted, “I left my regiment at 12 no. today.” He proceeded to give his interrogators full details on the location of Stevenson’s division, including the number and placement of artillery. In explaining his desertion, Cooper asserted that “there were fourteen North Carolinians belonging to Reynolds’ brigade shot last Thursday. . . .[T]his has caused much dissatisfaction and insubordination throughout the division.”[4]

On May 13th the Federals occupied Dalton, as Johnston fell back to Resaca. While passing through the deserted Confederate camps, Lt. Ralsa C. Rice, in Company B of the 125th Ohio, took note of an odd sight: “A number of stout posts set in a row. . . .[A]t a loss in finding a purpose” for them, Rice left the ranks to inspect the standing timbers. “On closer inspection I saw bullet marks in each post and blood stains on the ground.” Rice had his answer: It was the killing ground where fourteen Rebel deserters had been shot on May 4. “Thus, the Confederate government under Jeff Davis was making treason odious.”[5]

[1] “Reports of Prisoners of War and Deserters,” Army of the Cumberland Provost office, Record Group 393, NARA.

[2] Daniel, Soldiering in the Army of Tennessee, 112-113; Richard W. McMurry, ed., An Uncompromising Secessionist, The Civil War of George Knox Miller, Eighth (Wade’s) Confederate Cavalry (Tuscaloosa, AL: 2007), 189; “Dear Wife,” May 4, 1864, Semmes Family Papers, TSLA.

[3] “Deserters shot in Dalton, Georgia,” Augusta (GA) Daily Constitutionalist, May 5, 1864; Michael C. Hardy, The Fifty-Eighth North Carolina Troops. Tar Heels in the Army of Tennessee (Jefferson, NC: 2010), 106-108; Bromfield L. Ridley, Battles and Sketches of the Army of Tennessee (Mexico, MO: 1906), 285-286; SOR 7, 115; “My Dear Mother,” May 5, 1864, George Phifer Erwin Letters, UNC.

[4] “Statement of William E. Cooper,” Intelligence reports received by General Thomas, 1863-65,RG 393.

[5]Ralsa C. Rice, with Richard A Baumgartner and Larry M. Strayer, eds. Yankee Tigers, Through the Civil War with the 125th Ohio (Huntington, WV: 1992), 91.

This series will, I predict, rival your Chickamauga trilogy for its contribution to the literature. I am very excited to be publishing it, Dave.

Great start to the Atlanta series… Interesting that these Rebel executions occurred just as Sherman was commencing his Atlanta Campaign (initially scheduled for May 1st but then, put back a few days.) It appears that “a powerful message was being sent” by Confederate authority.

Tangentially, it boosts the rationale for the “backwater war” conducted by the Union army against the Native Americans west of Minnesota after 1862: many “former Rebels” were sent away to fight in that theatre, who might otherwise have been incarcerated with die-hards in Chicago or Rock Island… and perhaps not survived the POW experience.

For my personal taste, there is too stark a contrast between the first two Wednesday installments. Might the third fit a more conventional approach to a subject as multi-faceted as The Atlanta Campaign?

As I research, and especially as I read contemporary soldier letters and diaries, I am struck by how stark the contrasts of war really are.

Thank you for making us think about these inconvenient facts.

Besides the “reinforcement of discipline” enacted via executions authorized by General Johnston, other events of note took place in the months leading up to the 6/7 May 1864 commencement of the Union push towards Atlanta:

MGen William T. Sherman and LGen U.S. Grant met at the Burnet House in Cincinnati on 20 March 1864 to discuss strategy for Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign.

Sherman and McPherson met at Nashville about 25 March. McPherson had been authorized leave to visit Baltimore and marry his fiancé; but Sherman revoked this Leave in order to keep McPherson in theatre for preparations/ reconnaissance required.

Long supply lines, mostly comprising a single rail line from Northern supply depots to the emerging Union Supply Depot of Chattanooga, constituted a major threat to success of Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign, which could have been disrupted by Rebel cavalry.

Where is Forrest? During March/ April 1864 Nathen Bedford Forrest, a known threat to the Union rear, was rumored to be at Paducah… Hickman Kentucky… south of Memphis… somewhere in West Tennessee. On 12 April Forrest turned up at Union-occupied Fort Pillow, north of Memphis; after defeating the garrison there, numbers of surrendered Black soldiers were wantonly gunned down by the Rebels. In order to avoid direct blame for the massacre falling upon the Commander of the Atlanta operation (which occurred inside Sherman’s Military Division of the Mississippi) Major General Stephen Hurlbut, the Commander at Memphis, was accused of “not following orders” and saddled with responsibility for the Massacre at Fort Pillow.

Union-occupied Knoxville. Even after the last Rebel attempt to wrest control of Knoxville failed in December 1863, the possibility “of yet another Rebel attempt” loomed large; and any determined Rebel effort could have resulted in MGen George Thomas being forced to detach troops from the Atlanta Campaign preparations (control of Knoxville was a pet project of President Lincoln.)

The need to fortify Union bases of operation and supply in the rear, while creating the largest possible attacking force at the front led Ohio Governor John Brough to advocate for “100 Days’ Men” …soldiers who would be called into service across the Midwest for 100 days, put into positions near the Ohio River to prevent Rebel incursions further north, and free up trained Union soldiers for use at the front. These 100 Days’ Men began to appear during Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign (and became especially prevalent at Nashville, the main base of Union supplies.)

I would have to think that these repeated numbers of deserters was a boon in the mind of Sherman. I haven’t studied his correspondence with this tint in mind. As presumably you have. Did he say anything about it ?