“This Unparalleled Outrage…”: An Antebellum Raid on a Federal Arsenal, Part 3

“The democratic papers, says the O.S. Journal [Ohio State Journal], speak of the capture of the United States Arsenal as unprecedented in the history of this nation. The truth of history requires that this should be corrected. In 1855, on the 4th of December, the United States Arsenal at Liberty, Missouri was seized in a manner which undoubtedly formed the precedent for Brown’s seizure at Harpers Ferry.” – Wyandot Pioneer, November 3, 1859[1]

John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry is widely acknowledged as a cataclysmic event that propelled the United States towards civil war, one contemporary newspaper pronouncing that the raid “advanced the cause of disunion more than any other event.”[2] From October 16 – 18, 1859, Brown and his army of 21 men invaded Harpers Ferry, Virginia, capturing the Federal armory, arsenal, and rifle factory, and taking dozens of prisoners, all with an eye towards ending the institution of slavery. In less than 33 hours the raid was suppressed, with ten of Brown’s men killed, and Brown and six others captured. Over the following weeks Brown’s trial on charges of murder, conspiracy, and treason, splashed across newspapers north and south, forcing even the ambivalent to choose sides on the issue of slavery.

John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry is widely acknowledged as a cataclysmic event that propelled the United States towards civil war, one contemporary newspaper pronouncing that the raid “advanced the cause of disunion more than any other event.”[2] From October 16 – 18, 1859, Brown and his army of 21 men invaded Harpers Ferry, Virginia, capturing the Federal armory, arsenal, and rifle factory, and taking dozens of prisoners, all with an eye towards ending the institution of slavery. In less than 33 hours the raid was suppressed, with ten of Brown’s men killed, and Brown and six others captured. Over the following weeks Brown’s trial on charges of murder, conspiracy, and treason, splashed across newspapers north and south, forcing even the ambivalent to choose sides on the issue of slavery.

Many were quick to draw comparisons between Brown’s recent raid at Harpers Ferry and the invasion of the arsenal at Liberty, Missouri less than four years earlier. After explaining the particulars of the raid, the Wyandot Pioneer continued that…

“The seizure of an arsenal was to procure arms for the celebrated Missouri invasion against Lawrence, an expedition not much worse than Brown’s, except that his was to free slaves, and theirs to murder freemen to make a way for slaves. This sort of thing has gone far enough. We are glad the government has had its attention called to it. It was singularly resigned to the Missouri affair, but the recent repetition shows that such things are infectious. Now we call on the President to go in vigorously. All these Missourians can be found, without doubt. They have an excellent gift of preserving their own hides. These leaders probably hold government appointments; that is the haven to which most of these patriots drifted. Judge J.T.V. Thompson is no doubt high in authority in Missouri. So also Captain Rice…and Mr. Rout. Let the government indict and hang these insurgents that seized a United States Arsenal, these invaders of a peaceful territory, and these traitors to the nation. This will be an excellent preparation for the execution of Old Brown. Then all the people will exalt the justice of our government. But if all these insurgents, robbers, murderers and traitors, are to go free, and Old Brown is hung, the people and future generations will call it a cowardly murder, totally destitute of the first principle of justice.”[3]

The following month U.S. Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois delivered a lengthy address on the senate floor, defending his Republican party against southern attacks seeking to align Republicans with John Brown…

The following month U.S. Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois delivered a lengthy address on the senate floor, defending his Republican party against southern attacks seeking to align Republicans with John Brown…

“It seems that the arsenal at Liberty was broken up, and what remained of the arms were shipped to other military posts. Now, sir, there is a very striking similarity between the breaking into that arsenal and the attack upon the one at Harpers Ferry. The question of slavery had to do with both. The arsenal in Missouri was broken into for the purpose of obtaining arms to force slavery upon Kansas; the arsenal at Harpers Ferry was taken possession of for the purpose of expelling slavery from the state of Virginia – both unjustifiable, and it seems to me both proper subjects to be inquired into.”

“Perhaps the latter would never have occurred if inquiry had been made, and the proper steps had been taken when the cry came up from Kansas of these outrages, and when citizens of Kansas were murdered by the very army taken from this arsenal, or at any rate by persons in the same army with them. Then the complaints that were made were treated as the “shrieks of bleeding Kansas,” and they could not be heard. I trust they may get a better hearing now. Now, sir, when the shrieks of Virginia are heard, and the ears of the country are opened, I trust those from Kansas may get a hearing also. I am prepared to hear both; and I hope that the investigation in regard to Harpers Ferry may be impartial, thorough, and complete, and let whoever is implicated in the unlawful transactions there be held responsible; and so, too, in regard to the seizure of the arsenal in the state of Missouri.”[4]

That both raids focused on the institution of slavery is perhaps the easiest comparison to draw, as they diverge quickly from there. The Liberty raid had been orchestrated by pro-slavery Missourians intent on seeing Kansas admitted tot he Union as a slave state, while Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry sought to attack the institution in its stronghold of Virginia. If Brown could drive slavery from one county in Virginia, he could weaken in the institution in the entire state, thereby weakening slavery throughout the South.

That both raids focused on the institution of slavery is perhaps the easiest comparison to draw, as they diverge quickly from there. The Liberty raid had been orchestrated by pro-slavery Missourians intent on seeing Kansas admitted tot he Union as a slave state, while Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry sought to attack the institution in its stronghold of Virginia. If Brown could drive slavery from one county in Virginia, he could weaken in the institution in the entire state, thereby weakening slavery throughout the South.

It’s a matter of some conjecture whether the raid at Liberty “formed the precedent” as the Wyandot Pioneer suggests, though the possibility is tantalizing. We know Brown was in Lawrence, Kansas, in December 1855, steeled against the looming attack by the border ruffians who were armed with the very weapons that had been stolen from the Liberty arsenal. The widespread reporting on the Liberty raid would likely have caught Brown’s attention, though to this author’s knowledge Brown left no record of the Liberty raid serving as an inspiration for his own later raid.

Even if Liberty had piqued Brown’s interest – and perhaps contrary to popular belief – Brown’s survivors did not abscond from Harpers Ferry with any government weapons, nor did Brown make any such attempt. By Brown’s own admission, he believed his own Sharps rifles were superior to those weapons produced at Harpers Ferry. Indeed, plans were affected to move Brown’s arsenal from the Kennedy farmhouse to a schoolhouse nearer the Ferry where they could be more quickly accessed. Rather than stealing away from the Ferry with wagonfuls of weapons as the Missourians had from Liberty, Brown’s wagon brought from the Kennedy Farmhouse to Harpers Ferry was found after the raid to have been packed with “pikes, picks, shovels,” and “kindling bark saturated with fluid,” seemingly materials to sustain Brown’s command for an envisioned campaign in the mountains.[5] Thus, while Brown’s command was eventually hemmed in and captured, negating any opportunity to steal away with the Harpers Ferry weapon cache, Brown also made no preparations to do so.

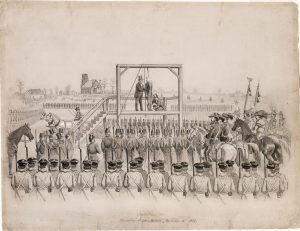

(Harper’s Weekly)

The two raids were equally distant in terms of violence. While no assault on a government facility (past or present) could be deemed peaceful, the Liberty raid resulted in no bloodshed or loss of life. Only a small handful of government employees were briefly detained. Meanwhile, the Harpers Ferry raid left sixteen individuals dead (including civilians and raiders), others injured, and dozens of private citizens and government employees held hostage for hours. Brown had entreated his men to avoid taking the life of any individual during the course of the raid, but allowed his men that “if it is necessary to take life in order to save your own, then make sure work of it.”[6] The violence that quickly erupted ensured that reprisal and punishment would be swift.

And as Lyman Trumbull pointed out, the resulting punishment for the raids could not have been further apart. The Missouri raid resulted in no arrests, no trials, and no fines. Even Colonel Edwin V. Sumner lamented that he could not risk apprehending the guilty parties “without taking sides in this momentous quarrel.”[7] By comparison, Brown and six of his compatriots were quickly tried and found guilty of treason against the Commonwealth of Virginia, murder, and conspiracy. The quick trial and execution were as much out of vengeance as they were a deterrent from any who might be inspired by Brown’s actions, just as much as Brown might have been inspired by the raid at Liberty.

It’s easy for us today to try and pigeonhole John Brown as a zealot, a fanatic, or a terrorist. We want to make Brown fit into our times and our understanding of how violent events have shaped our world. Rather, we should approach John Brown within the context of his time. Brown was very much a man of his time, and a product of the violence he witnessed, suffered, and inflicted in Kansas. At various times Brown could be counted as victim or aggressor.

All of this is to say Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry was not an unprecedented event. The December 1855 raid at Liberty, Missouri served as an earlier example of using force against a government installation to spark further action on the slavery issue, and maybe – just maybe – served as an inspiration for “the meteor of the war.”[8]

[1] Wyandot Pioneer, November 3, 1859

[2] Richmond Enquirer, October 25, 1859

[3] Wyandot Pioneer

[4] Trumbull, Lyman. On Seizure of Arsenals at Harper’s Ferry, Va., and Liberty, Mo., and in Vindications of the Republican Party and Its Creed, in Response to Senators Chesnut, Yulee, Saulsbury, Clay and Pugh. Washington, DC: Buell & Blanchard. 1859.

[5] Baltimore Daily Exchange, October 19, 1859

[6] Villard, Oswald G. John Brown, 1800 – 1859: A Biography Fifty Years After. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. 1910. 433.

[7] Mullis, Tony R. Peacekeeping on the Plains: Army Operations in Bleeding Kansas. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. 2004. 162

[8] Melville, Herman. The Works of Herman Melville – Standard Edition: Volume XVI. London: Constable and Company Ltd. 1924. 6.

Luckily, we don’t have to worry any more about what is or isn’t an insurrection, nor what the proper punishment should be.

Great series of articles! On a topic so long neglected…

In an attempt to answer the question, “Why was nothing done to the perpetrators of the Liberty Arsenal arms theft” the following details have come to light:

– In 1854, and again in 1855, census in the Territory of Kansas was conducted in order to “record the people of Kansas then resident; and from that total number of residents determine the number of residents actually eligible to vote in Territorial elections”

– Upon learning that “only residents of Kansas Territory were eligible to vote” there was public outcry in Missouri (reflected in the papers of the day)

– In November 1854, and again in 1855 the total number of votes cast at elections far exceeded the number of eligible voters; but the results of those elections (mostly for Democrat pro-slavery candidates) were allowed to stand;

– In response to “perceived” fraudulent elections, the Free-soil settlers of Kansas Territory began meeting to construct a Territorial Constitution; those meetings took place at Lawrence in August and Big Spring in September 1855;

– While the shadowy Constitution Convention was underway, Governor Andrew Reeder was dismissed (supposedly for acknowledging the fraudulent nature of Territorial elections); he was replaced by Wilson Shannon, who was sworn in as Governor in September 1855;

– After completing deliberations, what became known as the Topeka Constitution began to be drafted in October 1855 (with a vote on that Territorial Constitution to take place as soon as the document was finished)

– It may be that word leaked out of the impending vote; and Missouri “pro-slave voters” may have felt excluded… and then Free-soil settler Charles Dow was murdered, supposedly due to a property dispute. In process of tracking down Dow’s murderer, the admitted killer, pro-slavery resident Franklin Coleman was allowed to go free; and the man who owned the disputed land, Jacob Branson, was taken into custody by pro-slavery Sheriff Samuel J. Jones. (Jones figures prominently in a later event in Territory history.)

– Incensed by the “fraudulent application of justice” a posse of Free-soil settlers pursued Sheriff Jones and his party, rescued Branson, and spirited him away to Lawrence KS;

– Sheriff Jones complained to Governor Shannon; and Governor Shannon called out the Kansas Militia on 27 NOV 1855.

– It was later determined that as many as 2000 Missourians (including our visitors to Liberty Arsenal) helped make up the numbers for “restoring order to Kansas Territory”

– On 4 December 1855 weapons were taken from the Liberty Arsenal. But where did the raiding party come from? According to “The National Era” of 29 May 1856 the raiders stopped first at the Jefferson City Missouri Arsenal (actually the State Militia Armory) and collected weapons there, first. Since Missouri Governor Sterling Price controlled access to that Militia Armory, did HE authorize the removal of weapons?

– As regards the Liberty Arsenal, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis was ultimately responsible for the sanctity of that facility. But it appears that neither Governor Price (soon to be Rebel Major General Price) nor SecWar Davis (soon to be Leader of the Southern Rebellion) found it necessary to press charges for “misappropriation of weapons.” Perhaps by merely “calling out the Militia” Kansas Territorial Governor Shannon provided the necessary cover for “temporary acquisition” of weapons?

[The Topeka Constitution was approved on 15 December 1855 by a vote of 1731 to 46. But the worst in Kansas was yet to come…]

For Kansas Territorial Governor Shannon’s role in defusing the Wakarusa War, see the Tony R. Mullis report at https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/wakarusa-war

Senator Charles Sumner, the Siege of Lawrence, and the Cost of Speaking Truth:

The above series of articles by John-Erik Gilot, revealing details of “a forgotten theft of weapons” from the Arsenal at Liberty, Missouri has been more than thought provoking…

As stated in Part Two, “Captain W.N.R. Beall [conducted an inventory] and determined that the raiders of Liberty Arsenal had absconded with 55 rifles, 67 sabres, 100 pistols, 20 Colt revolvers, and THREE pieces of artillery.” Yet on 18 DEC 1855 the Missouri Daily Republican reported (page 3 col.1 “From Lawrence, dateline Dec 6th”): “Our forces… are 1200 pro-slavery men, eager to demolish Lawrence, and are hardly restrained by Governor Shannon, who is on the ground… The pro-slavery party commands SEVEN pieces of artillery – six pounders.”

Governor Shannon was “on the ground” to see for himself the Hell he was about to release upon “the belligerent army of abolitionists” at Lawrence; but to be sure of his decision, he reviewed the true state of affairs… and realized that the townsfolk of Lawrence, women and children, were huddled for protection within the single ring of entrenchments, occupied by the 400 men of Lawrence… and it suddenly occurred to Governor Shannon that “he had been duped… lied to. The defenders of Lawrence were not the aggressors; HIS pro-slavery army of 1200, about to turn Lawrence into a charnal house, were the aggressors.” And the Governor ordered the Emergency Militia to stand down: a peace treaty was signed on December 8, 1855. The pro-slavery militia removed to Lecompton and dispersed; and the Free-soilers of Lawrence went on with their lives.

So, the Wakarusa War came and went… the “stolen” arms were returned without penalty; and no one paid much attention to the finer details (such as, “Where did those extra four cannon come from?”)

Until 19 and 20 May 1856, when Senator Charles Sumner spoke for several hours on the floor of the U.S. Senate, regaling Senators and The Press with a damning review of “The Crime Against Kansas.” [The full speech occupies the Front Page of the National Era of 29 May 1856, and in it, for the first time revealed to a National audience, the provider of “those extra pieces of artillery” was named as the State Arsenal at Jefferson City, Missouri.]

Not a big deal? Charles Sumner was caned two days after delivering this speech, supposedly for “offending the honor of Andrew Butler,” which act by Preston Brooks had the effect of diverting attention from the topic of Sumner’s speech… and Missouri’s OFFICIAL complicity in Bleeding Kansas went mostly unreported, and un-noticed.https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026752/1856-05-29/ed-1/seq-1/

In the interest of Balance, the view from “the other side of the ledger” in support of Slavery in Kansas Territory is here provided. The quote belongs to Benjamin Franklin Stringfellow, born 1816 in Virginia, who in 1839 moved to Missouri, practiced as an attorney, was elected to the Missouri House of Representatives, and from 1845- 49 served as Attorney General of Missouri. During “Bleeding Kansas” Benjamin Stringfellow functioned as one of the many Missouri-based Border Ruffians: “To those who have qualms of conscience as to violating laws, State or National, the time has come when such impositions must be discarded, as your rights and property are in danger; and I advise you, one and all, to enter every election district in Kansas, in defiance of [Territorial Governor] Reeder and his vile myrmidons, and vote at the point of the Bowie-knife and revolver. Neither give nor take quarter, as our case demands it. It is enough that the slave-holding interest wills it, from which there is no appeal. What right has Reeder to rule Missourians in Kansas? His proclamation and prescribed oath must be repudiated. It is your interest to do so. Mind that Slavery is established where it is not prohibited” – delivered 1854 in response to Andrew Reeder’s “residency requirement” as condition of voting in Kansas Territorial elections.

Possibly a better known advocate of slavery in the territories is the following: Born in Kentucky in 1807, and trained at Transylvania University as Lawyer, David R. Atchison moved to Missouri in 1829 and settled at Liberty. Elected to the Missouri State Legislature in 1834, he was appointed to fill a vacant U.S. Senate seat in 1843, and subsequently won election to that Senate seat, serving until 1855 (during which time Senator Atchison reportedly became “U.S. President for one day.”) Atchison, while Senator from Missouri, helped push the passage of the Kansas- Nebraska Act; and subsequently worked on the ground to further the cause of slavery in Kansas Territory. In Jay Monaghan’s “Civil War on the Western Border, 1854- 1865” is to be found the following quote attributed to Atchison (reported to have been uttered in 1854): “We are playing for a mighty stake. The game must be played boldly… We will be compelled to shoot, burn and hang, but the thing will soon be over… If we win we can carry slavery to the Pacific Ocean.” [Atchison was the major rival to Thomas Hart Benton in Democrat politics – Anties versus Bentonites – in Missouri.]