Battle of Fort Hindman: “Then Went Into Charge”

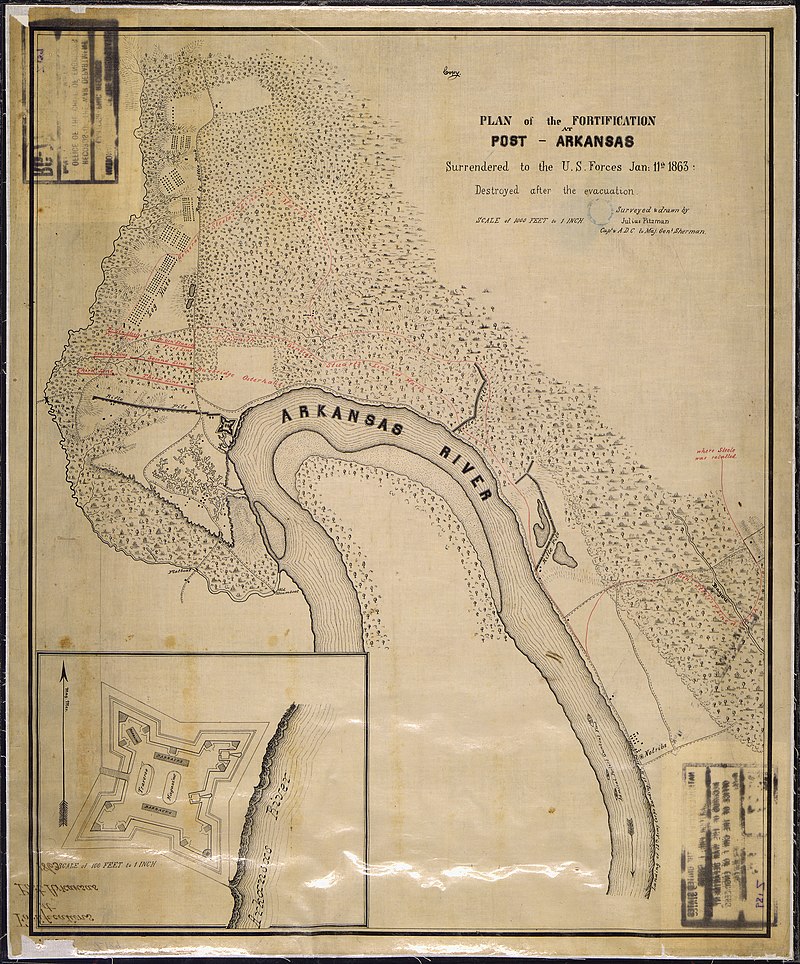

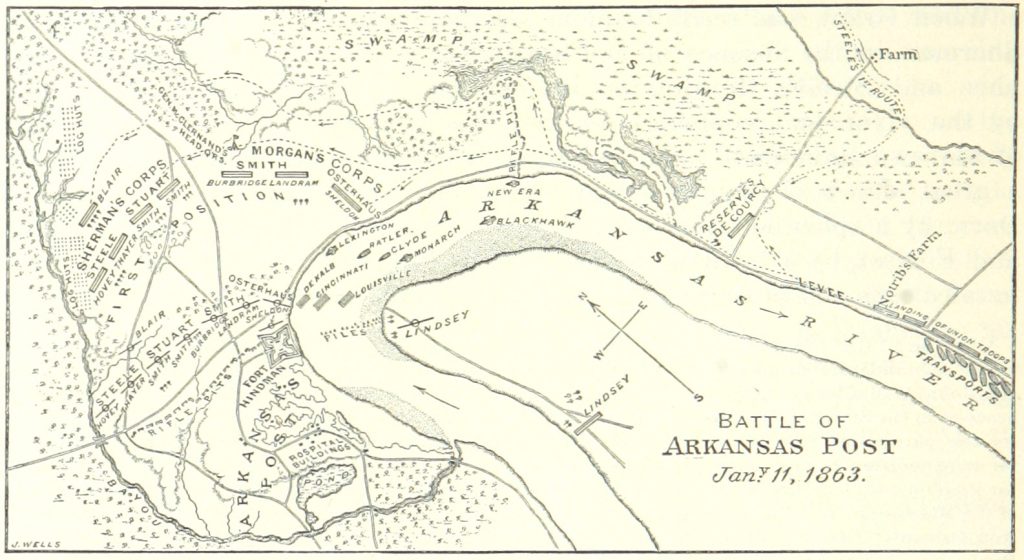

On January 10-11, 1863, military attacks occurred at Arkansas Post on the Arkansas River. About a week earlier on January 4, at a conference of army and navy commanders, General William T. Sherman proposed capturing the Confederate fort at Arkansas Post. The fort—located approximately 50 miles—up the Arkansas River from its juncture with the Mississippi River helped to protect the state of Arkansas’s capital and the fort had been attacking steam ships in its range. The reduction or capture of the Confederate stronghold at Arkansas Post would also eliminate an enemy position in the rear of Federal forces as they planned to move on Vicksburg later in 1863.[i] Sherman urged General McClernand and Admiral Porter to work together, though the two already had a rocky history. The admiral assembled his vessels, including three ironclads, and started for the Arkansas River on January 5.

Waiting at Arkansas Post, strong Confederate defensive works guarded the passage of the river. Fort Hindman stood at a commanding part of the river (a hairpin turn) with smaller fortifications below it along the river passage. Confederate General Thomas J. Churchill commanded the position and approximately 5,000 men.[ii] When he asked for reinforcements and directions, officials in Little Rock assured the Confederate defenders that help would be sent and that they should hold the fort at all costs. On January 9, the combined Union infantry and navy forces totaling approximately 30,000 men arrived three miles down river from the Confederate lines at Arkansas Post. The infantrymen disembarked, and both foot soldiers and navy men prepared for the attack.

On January 10, Union brigades maneuvered into position for the land-side attack with Admiral Porter’s gunboats started pounding the fort. Despite McClernand’s assurances that all were ready, the attacks did not coordinate on the 10th, delaying the main assault until January 11.

In the ranks of the 113th Illinois Regiment, forty-year-old Private Solomon Woolworth thought about the reality of a charge against these fortifications. A former grocer and butcher who had a shop on State Street in Chicago, Woolworth had not enlisted at first, thinking that the war would end quickly and could be fought mostly by the younger, more enthusiastic men. He had observed the political situation, and when a new call for volunteers had been issued in the summer of 1862, he decided to enlist and follow the footsteps of his ancestors who had fought in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Woolworth sold his store and joined the 113th Illinois Infantry, then spent three months in a training camp.[iii]

Woolworth’s memoirs suggest a distancing from his military comrades, even as the unit drew together through their training. He made quick and seemingly accurate judgments about officers and shook his head at the antics of “the boys”, likely prompted from his business experience and age. Woolworth understood the reality of going to war, and when the regiment left Chicago, he “bid Chicago good-bye, for I never expected to see it again.”[iv] Arriving in Memphis, the regiment had some experiences in skirmishing and repairing roads and bridges. Woolworth’s hesitancy about the regimental officers increased as he continued to observe their intemperate habits, and he gave strong suggestions to the officers when he felt they were making unwise decisions with the company or regiment.[v]

Private Woolworth disembarked with his regiment in preparation for the attack on Fort Hindman at Arkansas Post and marched through thick woods as artillery projectiles crashed through the woodland growth. The 113th Illinois was part of Smith’s First Brigade in Stuart’s Second Division of the XV Corps. In his memoirs, he later described the scene:

“There was a high spot of ground in front of us where we could see the rebel fort. A lot of us boys crawled up there, but the Rebels let us know they could see us as well as we could see them and fired a volley upon us…. There was no curiosity, after that, to see the rebel fort. We marched around behind the Rebel fort until about noon; then we received orders to charge the fort.

“The fort had two miles of intrenchment around it; this entrenchment was dug about half the length of a man. The logs were laid tight to one another until the last log was about two inches apart—so they could put their musket through it. The upper log would protect their head so they couldn’t be seen. Now they had tree tops which they cut down and sharpened every limb to a point. They put about two rods of this stuff in front of the entrenchment.

“Now you can imagine it would be a lively job to charge that entrenchment. The enemy was protect, while we had to crawl through those tree tops as best we could, while they were keeping up a continual fire on us.

“We had to stand a little while after we were ordered to charge, and the boys that were Christians took out their testaments and read them…. I gave myself into the hands of God and then went into charge.

“When we had marched a little way towards them we got orders to fall down and protect ourselves the best we could…. Now, when we fell, we hid ourselves the best we could behind stumps, rocks and little knolls…. We kept on crawling up and hiding ourselves behind anything we could find to protect us until we got within about ten rods of the enemy.

“There was a log pile where they had cut off the timber and piled it up in high piles. A great many of the boys were behind that, so I crept up behind it, but so many of them got there that the rebels were killing them at every volley. There was an oak tree about four rods in line with this pile of logs, and, if I could get there, I would be safe, so I asked God’s protection and went out. There was the full regiment of the enemy and I was a lone target, but when I reached the tree then I was comparatively safe, though some of the boys had crawled up behind me, they loaded their own guns and would hand them up to me; in this way I kept up a steady fire for three hours. One of the captains said: “They are getting the battery out so as to get range of us.” The captain yelled out: “Go for the battery!” and in less than three minutes there wasn’t a man or a horse left alive. Then the enemy surrendered.

“I was the first to see the white flag. I yelled, “They are surrendering!” but the boys said give them more, so they fired two or three volleys after this. Then the officers got a hold of it, and yelled cease firing, and then three or four officers went down and arranged for their surrender. It was an unconditional surrender. That night our officers took fifteen hundred ore that had come to help them. We opened the line and let them march right in and then informed them that they were all prisoners.”

Thoroughly battered on the river side by the gunboats and unable to counter the infantry attacks from the other side, the Confederates but started raising white flags around 4 p.m.[vii] While surviving soldiers breathed a heavy sigh of relief, officers at all levels started arguing. The Confederate officers argued about the meaning of the white flags, but the Union officers insisted on full surrender. Then McClernand and Porter went back to being at odds when the former did not mention or praise the navy in his report. In a twist of technological fate though, Porter sent off his report first—using a fast steamboat so Grant would read the navy’s report before the army’s arrived. As for the soldiers around the fort, during the following days, Woolworth helped to bury the dead and tear down the fortifications. He also continued to feel disgusted with his regimental officers who had a drunken celebration to celebrate the victory at Fort Hindman.

Though the expedition had captured the Confederate fortifications at Arkansas Post, Grant needed to keep a closer watch on McClernand and ordered him back to Mississippi. The reduction of Fort Hindman and Arkansas Post helped to secure Grant’s extended flank as he prepared to move against Vicksburg, and the victory gave a needed boost to Northern morale.

As for Private Woolworth, the battle of Fort Hindman proved the effectiveness of a soldier in the ranks to make decisions in the moment, especially when his regimental officers failed to step up with line leadership. Woolworth did not single-handedly force the Confederate surrender, but his initiative to seek out a position and his deadly, accurate fire did force a white flag to appear on that section of the fortifications. However, he did provide leadership from the ranks and survived that “lively job to charge that entrenchment” at Arkansas Post.

Sources & References:

See also Arkansas Post National Memorial website: https://www.nps.gov/arpo/learn/historyculture/stories.htm

[i] Robert S. Huffstot, The Battle of Arkansas Post, Civil War Times Illustrated. Accessed at https://www.nps.gov/arpo/learn/historyculture/upload/battle_of_ARPO_Booklet.pdf

[ii] Ibid.

[iii] Solomon Woolworth, Experiences in the Civil War, (1903). Page 3-4. Accessed through Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/item/03025277/

[iv] Ibid., 11.

[v] Ibid., 16

[vi] Ibid., 18-20

[vii] Ibid.

Great post, Sarah. It was an interesting battle of who surrender when and who surrendered to whom. Separately General’s McClernand and Sherman came up with the idea to move on Arkansas Post. Together they went to Rear Admiral Porter for his cooperation. Porter had a low opinion of political generals and McClernand was no exception. He had a low opinion of his abilities and was disgusted about his bragging. And he didn’t like the way McClernand treated his friend Sherman. For Sherman’s sake he agrees to personally lead the naval contingent. McClernand was slow to get his men into position on January 10 as Porter alone engaged the rebel batteries. Porter’s gunboats silenced most of the rebel guns before nightfall. The next day the gunboats re-opened the bombardment when white flags appeared. Porter landed with his sailors and climbed through the embrasures where Colonel Dunnington hands him his sword and surrenders the fort to Porter. To this Churchill is unaware and protests that he didn’t surrender but it is too late. While in the fort a large number of union officers approach Porter and an adjutant demands, “Get out of this fort. Everybody clear the fort. General [A.J.] Smith is coming to take possession.” Admiral Porter, dressed in a plain blue blouse with only shoulder strapes to indicate his rank replies, “Who are you, pray, that undertakes to give such an order here? We’ve whipped the rebels out of this place, and if you don’t take care, we will clear you out also.” At that point General A.J. Smith rode up. The two had never met before. “Here General,” said the adjutant, ” is a man who says he isn’t going out of this fort for you or anybody else, and that he’ll whip us out if we don’t take care.” “Will he, by God,” said General Smith. “Let me see him; bring the fellow to me. ” Porter stepped forward and said, “Here I am, sir, the admiral commanding this squadron.” At this announcement Smith laid his right hand on his holster of his pistol. Porter thought the General was going to shoot him. Instead, the General hauled out a bottle and said, “By God, Admiral, I’m glad to see you. Let’s take a drink.” A.J. Smith and Porter became fast friends which lasted through the war. McClernand, on the other hand, tried to garner all the credit for capturing the fort for himself in his official report. Anticipating this Porter sent in his own report vis the fastest steamer to the closet telegraph station to claim the victory for the navy and beat McClernand’s dispatch to the press.

Slendid article.

Enjoyed the article and learned. I can’t read about every skirmish and small battle but would like to. Comments are interesting, also.