The Last Casualty of Second Manassas: The Court Martial of Fitz John Porter

ECW welcomes back guest author Kevin C. Donovan

Abraham Lincoln laid down his pen. It was January 21, 1863. The President had just signed a document destroying the U.S. Army career and reputation of Major General Fitz John Porter. Specifically, Lincoln approved the findings and sentence of a court-martial, whose members had found Porter guilty of disobedience of orders and other misconduct during the Battle of Second Manassas (Second Bull Run).[1]

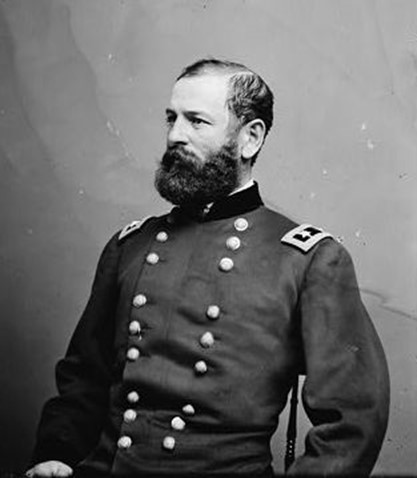

Before its ruin by the verdict of the court-martial Porter had experienced a long and honorable military career. A graduate of the West Point Class of 1845, where he stood eighth out of 41 cadets, Porter fought in the War with Mexico, earning two brevets (to Major) for gallant conduct. [2] Post-war, Porter served as a West Point instructor in natural and experimental philosophy and artillery-ironically, the identical role filled at the Virginia Military Institute by his future adversary, Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson-and as adjutant general for Colonel Sidney Johnston during the Mormon War of 1857-1858.[3] Porter served in key assignments in the months leading up to the Civil War, including being sent to inspect the defenses in Charleston Harbor (his resulting report led to the assignment of Major Robert Anderson to take command), before ultimately being selected by Major General George B. McClellan to command the Fifth Corps of the Army of the Potomac during McClellan’s Peninsula Campaign. [4]

Claiming he had been unjustly convicted, Porter spent years fighting to restore his good name. Finally in 1879 a military board, after hearing new evidence-including testimony from former Confederates-exonerated Porter.[5]

Porter’s post-war vindication does not mean that he was not properly convicted based upon the evidence available to the 1863 court. But to this lawyer-author a review of that earlier proceeding supports the conclusion that Porter was not treated fairly by that court.[6]

It is undisputed that at Second Manassas Porter disobeyed several of Major General John Pope’s orders. Porter repeatedly did not march or attack as Pope expected. Porter claimed he had good reasons for his battlefield decisions.[7] By contrast, the prosecution’s trial theory was that Porter, a close ally of McClellan and his politics,[8] deliberately withheld cooperation from Pope hoping that Pope would lose the battle, forcing the Lincoln administration to turn back to McClellan in the ensuing crisis. (McClellan, after his failure on the Virginia Peninsula, had been sidelined, and many of his troops transferred to Pope’s newly formed Army of Virginia, actions that angered McClellan and his supporters). [9]

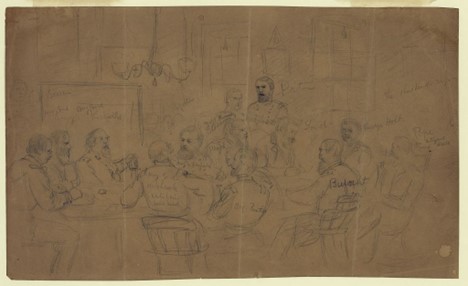

Wholly apart from the merits of the parties’ positions, the actions of the court during Porter’s trial beg scrutiny. A search for incipient judicial bias against Porter starts with looking at who comprised the court. First, a red flag arises from the fact that Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a McClellan enemy and ally of the “radical Republican” faction, hand-picked the nine generals appointed as Porter’s military judges. Stanton’s choices included the radical David Hunter, who would serve as presiding officer, other personal allies of Stanton or Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase (another anti-McClellan radical), Silas Casey, who had a grudge against Porter because Porter had caused his removal from command on the Peninsula, and two generals-Rufus King and James Ricketts-who were facing criticism for their own roles in the loss at Second Manassas and could avoid their share of blame by pointing the finger at Porter.[10] This looked like a “hanging” court.

The court also was illegal. The Articles of War mandated that when an army commander was the accuser, the President must appoint the court-martial.[11] The order creating the court and appointing its members instead had been issued by General-in-Chief Henry Halleck.[12] Indeed, one of its original members-William W. Morris-had questioned the court’s legality and been promptly replaced.[13] But when Porter’s counsel objected to the court, the court overruled the objection, adopting the fiction that Pope was not Porter’s accuser because Pope had had a staff officer sign the charges.[14] This was despite the fact that an earlier order by Halleck had recited that Pope had preferred charges against Porter.[15] Pope in fact had bribed the staffer, promising him a promotion if he allowed Pope to keep his skirts clean. This allowed Pope, when he testified against Porter, to adopt the guise of a simple truth-teller, rather than a vindictive battlefield loser looking for a scapegoat he could tar with the brush of treason.[16]

Having successfully preserved its existence, the court proceeded to embark on a course of hypocrisy and inconsistent application of its supposed rules of evidence, in each instance prejudicing Porter’s ability to defend himself. For example, early in the trial, when Pope found himself unable to answer a defense counsel’s key question on an issue supporting Porter’s innocence, the court bailed out Pope, ruling that the question sought irrelevant evidence. The question was so clearly proper that even the prosecutor had not bothered to object. Yet the court allowed Pope to refuse to answer, then adjourned for the day.[17] This gave Pope the opportunity to huddle overnight with the prosecutor to come up with a response. The prosecutor was Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt, a Stanton crony who owed his job to the War Secretary.[18]

When Pope again faced having to give an answer that would support Porter’s position, a member of the court unilaterally stepped in to rule that the question improperly sought an “opinion.”[19] The court refused to heed defense counsel’s arguments, while firmly announcing that “opinions” would not be permitted in testimony. It then blithely allowed multiple prosecution witnesses to offer their opinions adverse to Porter-such as speculating how the battle would have gone had Porter followed orders-overruling the objection of Porter’s counsel that the court already had barred so-called opinion testimony, at least when it might help Porter.[20] The court also unilaterally stepped in on other occasions to announce that prosecution witnesses need not respond to questions when the answers might help Porter.[21] Holt did not even have to object; the court was doing his job for him.

The court’s willingness to protect the prosecution’s witnesses in trouble during cross-examination and its application of a double standard on the issue of opinion testimony were not its only questionable actions. It also showed itself willing to permit prosecution witnesses to characterize Porter’s state of mind, bereft of any factual support. Indeed, while court members were quick to block Porter from asking questions designed to support his defense, they turned lethargic when adverse, yet clearly improper, testimony was elicited about Porter’s allegedly treasonous hidden thoughts.

For example, the officer who had delivered one of Pope’s orders was permitted to express his belief that Porter intended to disobey that order. The witness could offer no actual support for that belief; he admitted that Porter never said he would disobey the order. Yet his unsupported musing evoked no objection from the court.[22]

Worse, the court permitted Lt. Col. Thomas Smith, Pope’s aide, to offer a veritable psychological profile of Porter, whom Smith had never even met before the battle.[23] Smith became a key prosecution witness, as he offered his opinion on Porter’s manner when discussing Pope and his orders, describing it as “sneering and indifferent.” Smith was allowed to comment on Porter’s body language, saying that Porter’s mannerisms showed hostility toward Pope. Indeed, according to Smith, Porter’s expressions “looked to me like those of a man with a crime on his mind”-all this from a witness whose total interaction with Porter was a ten-minute conversation. [24] The court also permitted Smith to repeat an inappropriate and highly inflammatory opinion he had offered to Pope on the evening of August 29: “I was so certain that Fitz-John Porter was a traitor, that I would shoot him that night, so far as any crime before God was concerned, if the law would allow me to do it.” [25]

The court also continued to take an active role in Porter’s prosecution. When Porter’s counsel effectively cross-examined Major General Irvin McDowell, the next day McDowell was recalled, not by the judge advocate, but by the court. The court proceeded to rehabilitate McDowell by pitching him a series of leading questions clearly intended to portray Porter in as bad a light as possible by eliciting additional facts that the prosecution had not thought to offer.[26] Further, despite the court’s prior admonition to Porter’s counsel that opinion testimony was forbidden, a court member asked McDowell to repeat his damaging opinion of Porter’s inaction: “Had the accused made a vigorous attack with his force on the right flank of the enemy at any time before the battle closed, would, or would not, in your opinion, the decisive result in favor of the Union army, of which you have spoken, have followed?” McDowell answered, “I think it would.” [27]

Even this activism was not enough. Possibly concerned that Porter’s able counsel was building a record of the court’s inconsistent application of the rules of law-the press was present, recording the proceedings-on December 15, in the middle of the trial, the court decided to strip Porter of his attorney, saying that to save time it wanted Porter personally to examine his own witnesses and deliver legal arguments. Porter was no lawyer, and suddenly forcing him to act as his own counsel would cripple his defense. Porter replied that he would insist upon his right to submit questions to witnesses in writing. This would result in delay far more extensive than continuing to allow his counsel to frame cross-examination questions immediately after each witness completed his direct testimony. Caught in the illogic of its own supposed rationale, the court grudgingly backed down. [28]

Other instances of the court placing its thumb on the scales of justice were refusing to order the prosecution to produce exculpatory evidence sought by Porter’s counsel and refusing to admit into evidence other documents tending to exonerate Porter.[29]

Finally, near the close of the trial, Brig. Gen. Rufus King, a member of the court, took the stand to provide testimony against Porter, essentially calling one of Porter’s key witnesses a liar.[30] Remarkably, King then resumed his seat on the court and participated in deliberations.

King’s conduct was just one aspect of a thoroughly suspect proceeding. Porter’s defense team was handcuffed throughout the trial by the court’s prejudicial rulings, and its inconsistent positions on evidence, including on when opinion evidence was allowed. Moreover, the court was not above intervening to help prosecution witnesses when they found themselves in trouble on cross-examination.

In his January 19, 1863 report on the proceedings to President Lincoln, Colonel Holt declared that the trial had been fair and that the court had strained to give Porter every possible element of due process, stating: “The court was not only patient and just, but liberal, and in the end everything was received in evidence which could possibly tend to place the accused in its truelight. It is not believed that there remains upon the record a single ruling of the court to which exception could be seriously taken.” [31]

Holt’s assurance would be comical, but for the consequences visited upon Porter by the court’s decision. Holt’s report, a woefully one-sided and deceit-filled purported summary of the over 900 pages of court transcript, was widely disseminated, even in the western armies. This helped to ensure that Porter stood convicted in the mind of many in the armies and the public generally. It is doubtful that even Lincoln attempted to wade through the massive court transcript, instead allowing himself to be swayed by Holt’s poisonous distillation of a fatally flawed judicial exercise.[32] The conclusion is inescapable: despite Holt’s high-sounding language, the Porter trial was not a shining example of military justice in action, and with that stroke of Lincoln’s pen, Fitz John Porter became the last casualty of the Second Manassas.

Kevin C. Donovan, Esq., a retired lawyer, now focuses on Civil War research and writing, including on law-related topics such as “How the Civil War Continues to Affect the Law,” published in Litigation, The Journal of the Section of Litigation, of the American Bar Association. His inaugural ECW blog publication, “A Tale of Two Tombstones,” appeared December 9, 2022 and was ECW’s most popular post of the year on social media.

[1] U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, ser. 1, vol. XII, pt. 2, Supplement (Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), 1052; William Marvel, Radical Sacrifice: The Rise and Ruin of Fitz John Porter, p. 293 (The University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, NC 2021).

[2] Radical Sacrifice, pp. 12-13, 32.

[3] Radical Sacrifice, pp. 32-33, 43-44; James I. Robertson, Jr., Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend, p. 107-108 (Macmillan Publishing USA, New York, NY 1997).

[4] Radical Sacrifice, pp. 60-68, 120.

[5] Curt Anders, Injustice on Trial: Second Bull Run, General Fitz John Porter’s Court-Martial, and the Schofield Board Investigation That Restored His Good Name, pp. 293, 298-302, 405-407 (Guild Press Emmis Publishing, LP, Zionsville, IN 2002).

Lingering political animosity towards Porter caused another seven years to pass until he was reinstated to the Army. Injustice on Trial, pp. 413-415; Radical Sacrifice, pp. 339-345, 349-353.

[6] The court transcript and related documents are in the Official Records, ser. 1, vol. XII, pt. 2, Supplement, 821-1134 (hereafter “TR”).

[7] See closing argument of Porter’s counsel, at TR 1075-1112.

[8] McClellan and Porter strongly opposed both emancipation of the enslaved and the institution of so-called “hard war” tactics targeting disloyal citizens, policies being pressed on the Lincoln Administration by the so-called “radical” Republican faction. By the Summer of 1862, Lincoln was moving towards adoption of both policies. Radical Sacrifice, p. 183; Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The Committee on the Conduct of the War, pp. 126-127, 129, 134 (University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 1998).

[9] See “Review of the Judge-Advocate,” TR 1112-1133, especially TR 1113-1115; Radical Sacrifice, pp. 186-187, 225-229; Stephen B. Sears, George B. McClellan: The Young Napoleon, pp. 244-247, 258-259 (Ticknor & Fields, New York, NY 1988).

[10] Radical Sacrifice, pp. 100, 103, 266-268.

[11] Revised Regulations for the Army of the United States: 1861 (Appendix), p. 509, Article 65 (National Historical Society, Harrisburg, PA 1980).

[12] TR 821.

[13] TR 822; Radical Sacrifice, p. 268.

[14] TR, 829-830.

[15] TR, 828; Radical Sacrifice, p. 271.

[16] John J. Hennessy, Return to Bull Run, pp. 549-550, n. 12 (New York, Simon & Shuster, 1994); Radical Sacrifice, pp. 271-272. Pope later cheerfully took credit for bringing the charges against Porter, stating: “I considered it a duty I owed the country to bring Fitz-John Porter to justice…” Supplemental Report to the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, p. 190 (Washington, D.C., Government Printing Office, 1866), https://li.proquest.com/elhpdf/histcontext/1242-S.rp.142.pdf.

[17] TR, 838-839.

[18] Radical Sacrifice, pp. 228, 273-274.

[19] TR, 856-857.

[20] TR, 865, 868, 891, 903, 906.

[21] See, e.g., TR, 825, 865-866, 869.

[22] TR, 861-862, 888.

[23] TR, 892-893.

[24] TR, 888-890, 895, 899.

[25] TR, 889.

[26] TR, 911-914.

[27] TR, 903 (emphasis supplied).

[28] TR, 920-921.

[29] TR, 936-938.

[30] TR, 1035-1036.

[31] TR, 1132.

[32] Radical Sacrifice, pp. 294, 296-298; Injustice on Trial, pp. 259-260. Even before Holt’s piece appeared Pope’s trial allies, Roberts and Smith, had been circulating-among the press, in Congress and elsewhere-a pamphlet purporting to be a true record of the trial, but in fact it only included the evidence and testimony for the prosecution. This too prejudiced Porter in the eye of the public. Radical Sacrifice, pp. 293-294, 296; Injustice on Trial, pp. 243-244.

Given the insightful review and explanation of the Fitz-John Porter proceedings, it appears that every generation has its share of sham investigations/ kangaroo courts.

What an excellent and interesting article!

Indeed.

Thank you, George.

This post does a nice job of separating two different issues. Both of the following can be true at the same time: (1) the specific charges brought by Pope and resulting in conviction were the subject of a deeply flawed proceeding; and (2) Porter was no martyred hero (among other things, see Hennessy’s assessment of his performance in Return to Bull Run). The Schofield Board that exonerated Porter of the specific charges implicitly recognized the distinction. Unfortunately, some publications have commingled the two.

Wow! This article kicks butt and takes names! I printed it out and put it with my small collection of stuff on this topic. I especially like how it demonstrates a parallel to today’s “doings.”

Meg thank you so much. And I am immensely pleased to have found ECW and enjoying everyone’s wonderful articles.

Excellent, eye-opening report.

Another potentially interesting aspect to consider: in July 1862, following on the “euphoric success” of Henry Halleck and his 100,000 soldiers in accomplishing the nearly bloodless subjugation of the strategically important rail junction at Corinth Mississippi, Major General Halleck was called to Washington to assume the role of General-in Chief. And Halleck’s chief lieutenant and supporter, who had directed the pursuit of Beauregard after Corinth and assisted with “massaging the narrative,” making it appear as if “the Rebel Army in the West is dissolving before our eyes” (resulting in ending of the pursuit prematurely) was none other than John Pope. Bedazzled with Halleck’s success due to records created from bad information after Corinth, President Lincoln and Secretary of War Stanton called the Team of Halleck & Pope to Washington… and were likely surprised that Pope failed so miserably at Second Manassas… and were open to suggestions that “Western man Pope had been sabotaged by a cabal of Eastern officers committed to Pope’s failure.” In addition, then-Captain John Pope had accompanied President-elect Lincoln on his two weeks of Inauguration Train journey from Springfield Illinois in February 1861 and likely left Lincoln with a favorable impression.

After the dust had settled, and President Lincoln had “laid down his pen” in January 1863 George B. McClellan was “awaiting Orders” in New York; McClellan’s strong supporter, Porter, was no longer in the Army; and John Pope was sent away to fight Indians in Dakota Territory. Win – win – win.

Mike, thank you. Regarding your observation that bogus reporting of victory in the West propelled Halleck and Pope to promotion in the East, you might be interested in a 1912 work I ran across while researching the Porter affair. In “Antietam and the Maryland and Virginia Campaigns of 1862,” Isaac W. Haysinger claims that Pope blackmailed Halleck to force the dismissal of McClellan and the court-martial of Porter, based on Pope accusing Halleck of sending Lincoln the bogus dispatch falsely claiming that Pope had won a great victory, which then prompted Lincoln to bring both Pope and Halleck East, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/public/gdcmassbookdig/antietammaryland00hey/antietammaryland00hey.pdf. Haysinger says that Pope claimed that Halleck made up the victory report without any corrupt input at all from Pope. Pope indeed did serve as one of Lincoln’s bodyguards on the train journey to Washington for the inauguration (as did David Hunter, the future Court-Martial’s presiding officer). In addition, Lincoln knew Pope’s father, an Illinois judge before whom Lincoln had appeared as a lawyer on multiple occasions. There was even a distant in-law relationship (Pope’s second cousin was married to Mary Todd Lincoln’s sister).

Imo, Porter had his chance at Antietam to smash Lee in two, if only Mac had released the hounds – Porter’s 8 brigades, a chance which would have made Porter a hero and unassailable by court martial.

Porter had his chance at Antietam –

Due to a mix-up of orders, the Confederate infantry abandoned the position, leaving a large gap in the center of Lee’s line. McClellan witnessed all this from Porter’s Fifth Corps headquarters, but by now he was drained of all aggressiveness. He ordered the troops at the Sunken Road to stand on the defensive.

[Burnside needing help after being flanked by Hill…] Correspondent George Smalley was with the general commanding at Fifth Corps headquarters. McClellan, he wrote, “turns a half-questioning look on Fitz-John Porter, who stands by his side, and one may believe that the same thought is passing through the minds of both generals. ‘They are the only reserves of the army; they cannot be spared.’” Stephen Sears, from battlefields.org

“there would be no aggressive action that night or next day should McClellan listen to the advice of Fitz John Porter.”

Hooker, Joseph

Hooker to Ezra Carmen regarding any plans to attack at Antietam on the evening of Sep 15 or morning of Sep 16

Pierro, Joseph, ed. The Maryland Campaign of 1862. New York: Routledge, 2008 pg 180

Kevin C. Donovan

Thank you for directing me to Heysinger’s work. After finding it via onlinebooks I’m in process of reading it now. During research of operations in the West leading up to Shiloh and Corinth it became apparent that favoritism, personality conflict, and “a man’s reputation established at West Point” (used increasingly to determine WHO would command Divisions and Army Corps) were nearly as important as the Campaigns conducted. All the best.

Mike Maxwell

Having completed reading Heysinger’s work, the claims presented as they relate to the Siege of Corinth, the pursuit of Beauregard, and the fabrication of official information (that boosted Halleck’s chance of promotion) are on track. The only bits ignored relate to the “contributions” of Don Carlos Buell and Philip Sheridan. Having worked for Halleck at St. Louis late in 1861 “auditing claims” of the previous commander (MGen John Fremont) then-Captain Sheridan was promised an infantry regiment shortly after the Battle of Shiloh… but that opportunity fell through. While in the field with Halleck in May 1862 the 2nd Michigan Cavalry became available, and experienced infantry officer Sheridan became Colonel of that outfit. A few days later, during Pope’s Pursuit of Beauregard south of Corinth in early June 1862 Sheridan’s Michigan Cavalry was in the vanguard.

The Buell “interference” is important because MGen Don Carlos Buell (another friend of Halleck) was senior to MGen Pope; and after the Federal occupation of Corinth it appeared that “Rebellion in the West was in its death throes.” Beauregard’s remaining force was estimated as “about 30000 soldiers.” Buell pushed Halleck for command of the pursuit, and Halleck inserted him in an administrative role overseeing Pope’s activity in the field: both Pope and Buell were based at Booneville, 20 miles south of Corinth [OR 10 pt.2 p. 254]. When Pope required food and ammunition, he requested those from Buell. If Pope required reinforcements upon contact with the enemy, Buell was ready to provide them (and due to his senior rank, Buell would take overall command.) Otherwise, Pope reported directly to Halleck. And Halleck (thanks to a telegraph line Buell had strung all the way from Nashville to Corinth) was able to report progress directly to SecWar Edwin Stanton in real time.

The final result: Sheridan was anticipated to reach as far south as Guntown (37 miles from Corinth) but only reached Baldwyn (32 miles from Corinth.) Beauregard’s Army was at Tupelo (less than 15 miles from Guntown) and remained there, undiscovered and undisturbed. Pope reported on 8 June inflated “prisoner and deserter numbers” of 20,000 to Halleck. On 9 June MGen Pope reported, “Many of the Prisoners of War desire to take the Oath of Allegiance and return home… Colonel Sheridan is at Baldwyn, and his advance is pushed towards Guntown” [OR 10 pt.2 p.278]. MGen Buell reported to Halleck on 9 June 1862 that “between 20- 30000 Rebels are our prisoners, or have deserted” [OR 10 pt.2 p.279]. And Halleck called off the pursuit.

Mike, fascinating. Sounds like a good topic for a ECW post.

Again, thanks for the insight regarding Fitz-John Porter; and for introducing Civil War enthusiasts to the 1912 work by Isaac Heysinger. The nuggets of Truth revealed by veteran Union Army officer Heysinger are deserving of more attention.

Mike, my pleasure. It indeed is amazing what research resources are available on the internet.