Daniel Webster & the Devil

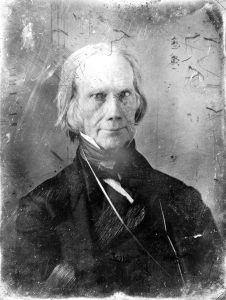

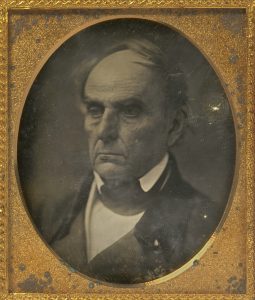

Today is March 7, the 173rd anniversary of Daniel Webster’s speech in support of Henry Clay’s final proposal to keep the states of America united, known as the Compromise of 1850. Lately, we think of such a compromise as a terrible idea because it allowed slavery to continue, but on January 21, 1850, the two men talked it over for hours, considering it as a way to keep the Union together. Clay had walked through snowdrifts to Daniel Webster’s home in Washington because he knew he had to have the support of the most renowned statesman and orator of the North if the Union was to remain together.

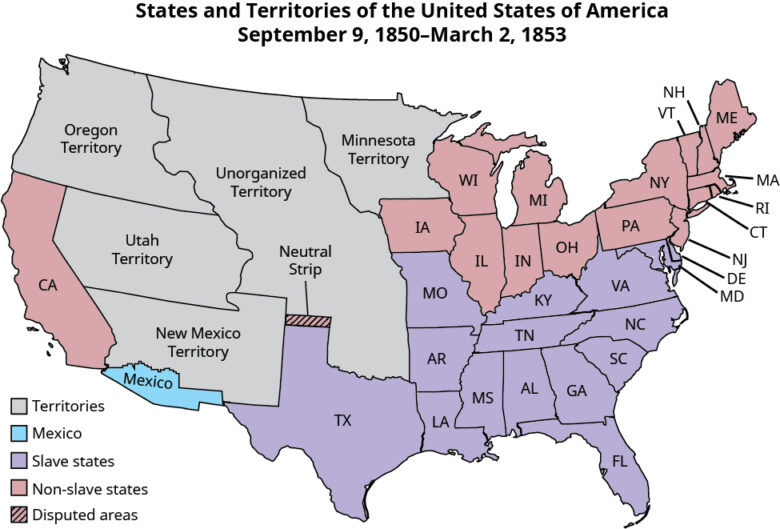

By 1850, all the currents of conflict, disunion, growth, decline, strength, and weakness, reached a climax. [1] California had applied for admission to America as a free state, upsetting the South. Most slaveholders felt that the geography and climate in the northwest were not conducive to expanding slavery. Only in the southwest could the South hope to balance the scales of power by allowing Mexico’s territories ceded to the U.S. after the Mexican War to enter the Union as slave states. Each slave state would add two senators to the supporters of slavery, thus keeping senatorial power firmly in the hands of the fire-eaters. Henry Clay trudged through the storm, knowing he had to get Webster’s help. The fate of the Union depended on it.

The Compromise of 1850—just an academic reminder, here—had five essential parts:

- California to be admitted as a free state

- Utah and New Mexico to be organized as territories neither for-or-against slavery

- Texas to be compensated for territory ceded to New Mexico

- Slavery abolished in the District of Columbia

- A re-written, more enforceable Fugitive Slave Law to be enacted

These are certainly compromises. No one was pleased. Southern senators were upset about California and the District of Columbia. In contrast, northern senators were unhappy about strengthening the Fugitive Slave Act and the idea that the whole argument might need reconsidering if and when Utah or New Mexico sought statehood. Daniel Webster opposed slavery, but the preservation of America overrode those feelings. That night he agreed to join Henry Clay.

The country was in a shaky condition. The South, of course, had a headwind in the secession area. John C. Calhoun wrote, “Disunion is the only alternative that is left for us.” In his last speech, he declared, “The South will be forced to choose between abolition and secession.” [2]

But the South was not the only part of the country considering secession. William Lloyd Garrison, journalist and editor of the anti-slavery newspaper The Liberator, and his followers threatened to seriously consider their own secession movement if Congress continued to placate southerners with the perpetuation of slavery. On July 4, 1854, Garrison publicly burned a copy of the Constitution, declaring that the document, if interpreted to support slavery, was an “Agreement with Hell.” [3]

On March 7, 1850, Daniel Webster made the only speech in history that is entitled by the date it was given: The “Seventh of March” speech. The Senate chambers were packed! After all, this was rumored to be a landmark presentation by one of the most famous speakers in Congress. Webster rose from his chair, wearing his signature blue tailcoat, a buff waistcoat, and breeches. He began:

Mr. President, I wish to speak today, not as a Massachusetts man, nor as a Northern man, but as an American, and a member of the Senate of the United States.… I speak for the preservation of the Union. Hear me for my cause. [4]

Webster then proceeded to speak for nearly three and a half hours. He pled the cause of Union, assuring his audience that the concern of the Senate was not slavery but the preservation of the United States of America. He pointed out that slavery was not going away where it already existed, nor was plantation agriculture going to extend to the dry, mountainous lands of the southwest. Geography was reality, and it was not going to change. He reminded Congress that enslaved people were property and that strengthening the fugitive slave laws would strengthen the ties between the South and North. So, again, there should be no change in the status quo, which was, apparently, Webster’s definition of “union.” But Webster greatly misread the effect his words would have on his constituency—the New England states—birthplace of abolition.

The telegraph got the “Seventh of March” speech into the newspapers nationwide. Webster won praise for his moral courage in the South and west, but his native New England slammed his effort. Some politicians asserted that Webster had made a deal (with the Devil!) to support southern positions on slavery in exchange for their collective support in the next presidential election. Writers and luminaries such as Horace Mann and Ralph Waldo Emerson were outraged. Emerson exclaimed,” ‘Liberty! Liberty!’ Pho! Let Mr. Webster, for decency’s sake shut his lips for once and forever on this word. The word ‘Liberty’ in the mouth of Mr. Webster sounds like the word ‘love’ in the mouth of a courtesan.” [5]

Abolitionists damned Webster in clear terms. Webster’s speech, moral courage aside, had ruined relations with his political base. As a result, Daniel Webster resigned from the Senate on July 22, 1850. He finished his public career as Secretary of State. Denied the Whig Party’s presidential nomination in 1852, he died later that year–in despair of the nation’s future.

______________________________________________

[1] John F. Kennedy, Profiles in Courage, Harper & Brothers, (New York), 1956. 55.

[2] Ethan S. Rafuse, “John C. Calhoun: The Man Who Started the Civil War,” HistoryNet, June 12, 2006, https://www.historynet.com/john-c-calhoun-the-man-who-started-the-civil-war/

[3] Paul Finkleman, “Garrison’s Constitution: The Covenant with Death and How It Was Made,” Prologue Magazine, National Archives, Winter 2000, Vol. 32, No. 4. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2000/winter/garrisons-constitution-1

[4] https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/Speech_Costs_Senator_His_Seat.htm.

[5] Ibid.

A relevant excerpt from “The Devil & Daniel Webster,” by Stephen Vincent Benet. (Here the Devil is telling Senator Webster his future):

‘You have made great speeches,” said the stranger. “You will make more.”

“Ah,” said Dan’l Webster.

“But the last great speech you make will turn many of your own against you,” said the stranger. “They will call you Ichabod; they will call you by other names. Even in New England some will say you have turned your coat and sold your country, and their voices will be loud against you till you die.”

“So it is an honest speech, it does not matter what men say,” said Dan’l Webster. Then he looked at the stranger and their glances locked. “One question,” he said. “I have fought for the Union all my life. Will I see that fight won against those who would tear it apart?”

“Not while you live,” said the stranger, grimly, “but it will be won. And after you are dead, there are thousands who will fight for your cause, because of words that you spoke.”

“Why, then, you long-barreled, slab-sided, lantern-jawed, fortune-telling note shaver!” said Dan’l Webster, with a great roar of laughter, “be off with you to your own place before I put my mark on you! For, by the thirteen original colonies, I’d go to the Pit itself to save the Union!”

And with that he drew back his foot for a kick that would have stunned a horse. It was only the tip of his shoe that caught the stranger, but he went flying out of the door with his collecting box under his arm.’

Brilliant, and a perfect addition. Huzzah!

I think the compromise entailed the end of the trade in slaves, i.e, “bringing into the District of Columbia, any slave whatever, for the purpose of being sold …” not slavery itself in DC.

Pres Taylor would be dead in July so it fell to Fillmore to complete the compromise. Fillmore seems to be popularly viewed as a political hack. That seems a bit uncharitable to me. Webster for his part had no real path to the Whig nomination in 52 but seems to have been instrumental in denying it to Fillmore resulting in Scott getting the nod which may have accelerated the decline of the party.

Actually, Meg, the birthplace of abolition was not New England but Pennsylvania, with the Society of Friends. And the term “fire-eaters” to describe the majority of Southern Senators in 1850 was a bit premature. A good article. I always felt that most of the zealots on both sides, being of “mature” age, were always more than willing to let others bleed for their ideals.

Great post, Meg!!