Did 8 Days Make a Difference? Thinking About Stonewall’s Wounding and Death

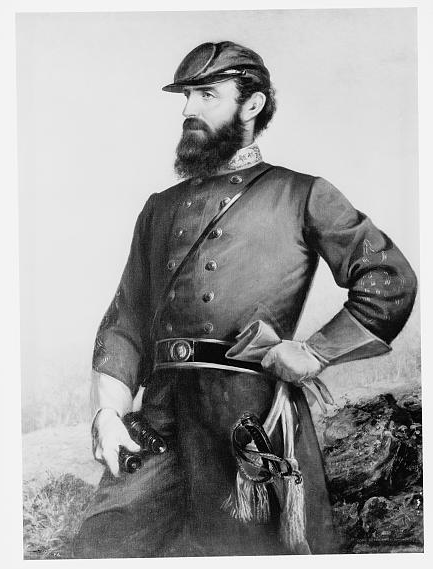

General Thomas J. Jackson was wounded by friendly fire during the night of May 2, 1863, during the battle of Chancellorsville. On May 10, 1863, Jackson died, and attending doctors believed pneumonia was the cause of death.

General Thomas J. Jackson was wounded by friendly fire during the night of May 2, 1863, during the battle of Chancellorsville. On May 10, 1863, Jackson died, and attending doctors believed pneumonia was the cause of death.

As I’ve been re-reading accounts of Jackson’s wounding and medical treatment over the past few weeks, one of the things that stood out is how near death he may have been during his battlefield evacuation. What if “Stonewall” had died that night on the battlefield? Would any outcomes have significantly changed if he had died on May 2 instead of May 10?

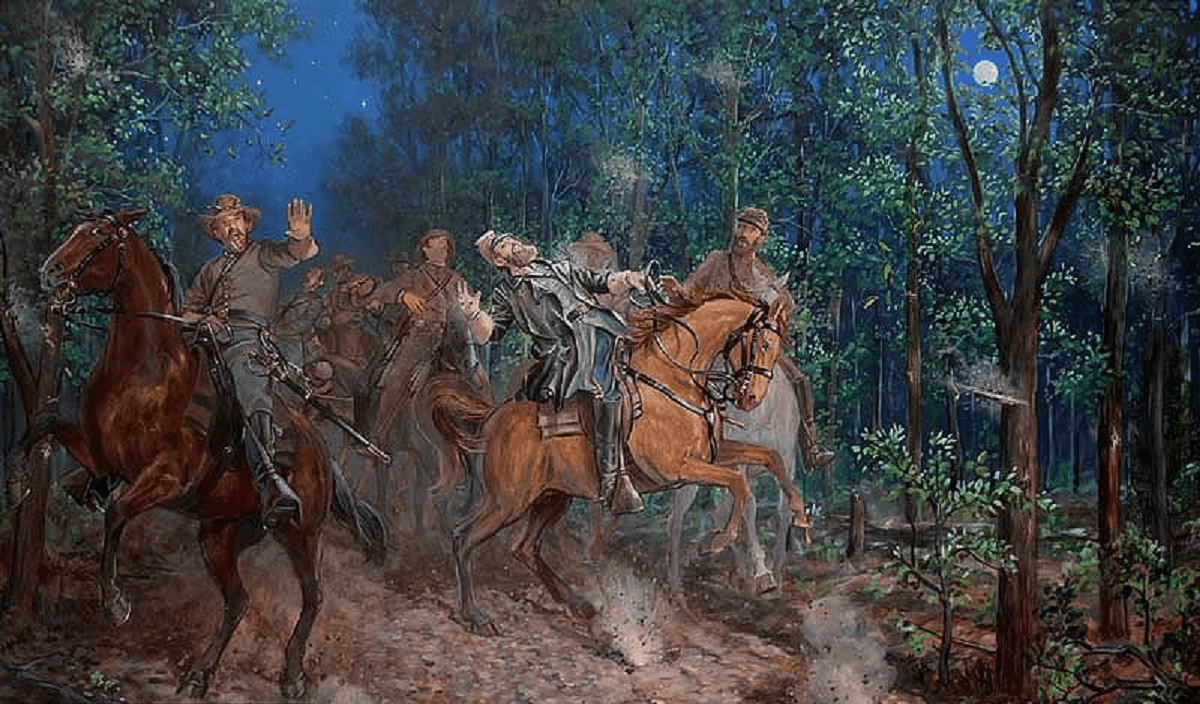

First, from eyewitness accounts, Jackson may have been close to death in the battlefield darkness of May 2 and he may have known it. Following his wounding (two bullets struck his left arm and one struck his right hand) and his horse’s dash through the woods, Jackson eventually dismounted and staff officers attempted to bandage his injuries. Then, Jackson attempted to walk toward the rear, supported by his aides-de-camp and described as nearly fainting. Eventually, they placed him on a stretcher. In the hurrying through the woods which were now illuminated by artillery blasts, the stretcher bearers dropped the general twice, causing him to groan “piteously.”

Dr. Hunter McGuire—medical director for Jackson’s Corps—found the general after he had been carried to an ambulance wagon. He answered the doctor’s inquiries “very calmly, but feebly,” and explained, “I am badly injured, Doctor; I fear I am dying…. I think the wound in my shoulder is still bleeding.”

McGuire later detailed in the condition he found Jackson in:

His clothes were saturated with blood, and hemorrhage was still going on from the wound. Compression of the artery with the finger arrested it, until lights being procured from the ambulance, the handkerchief which had slipped a little, was readjusted. His calmness amid the dangers which surrounded him, and at the supposed presence of death, and his uniform politeness, which did not forsake him, even under these, the most trying circumstances, were remarkable. His complete control, too, over his mind, enfeebled as it was by loss of blood, pain, &c., was wonderful. His suffering at this time was intense; his hands were cold, his skin clammy, his face pale, and his lips compressed and bloodless; not a groan escaped him—not a sign of suffering, except the slight corrugation of his brow, the fixed, rigid face, and thin lips so tightly compressed that the impression of the teeth could be seen through them….

While it’s not possible to diagnose 160 years later, it is possible to make some guesses. From the above description, it sounds like Jackson had suffered heavy blood loss and was probably in medical shock. The described 19th Century treatments that came next also suggest shock.

McGuire gave Jackson a mixture of whiskey and morphine and controlled the bleeding for the ambulance journey to the field hospital a few miles in the rear of the battle lines. Once they reached the field hospital near Wilderness Run, Jackson “was placed in bed, covered with blankets, and another drink of whiskey and water given him. Two hours and a half elapsed before sufficient reaction took place, to warrant an examination.” The delay points to the doctors deciding Jackson wasn’t physically stable enough for chloroform, a significant note since anesthesia, examinations, and surgeries were usually done as quickly as possible in battlefield medicine. Once able to proceed, the doctors used chloroform and then removed the smooth-ball from the generals right hand and amputated his left arm.

Over the next few days, Jackson’s wounds seemed to be healing, but mid-week, he exhibited early symptoms of lung trouble and the doctors diagnosed it as pneumonia. Their treatments—unsurprisingly to modern medicine—did little to heal. Like many diseases in the mid-19th Century, doctors knew enough about pneumonia to predict the day and almost hour of death by watching the patient’s decline, but could do little cure. About 3:15pm on May 10, 1863, “Stonewall” Jackson died.

From McGuire’s description and Jackson’s own words on May 2, Jackson’s physically condition was precarious that night. He could have died that night from blood loss if the bandages had slipped or loosened another time. When considering the military impact on the historical possibility of Jackson’s death that night, a few recorded incidents offer perspective.

First, Jackson was unable to offer direction for the battle after his wounding. As he recovered from the effects of chloroform and his amputation, one of his staff officers was allowed to see Jackson and explained that Stuart was taking command of the corps and “asked what should be done. General Jackson was at once interested, and asked in his quick rapid way, several questions. When they were answered, he remained silent a moment, evidently trying to think; contracted his brow, set his mouth, and for some moments was obviously endeavoring to concentrate his thoughts. For a moment it was believed he had succeeded…but it was only for a moment; his face relaxed again, and presently he answered very feebly and sadly, ‘I don’t know—I can’t tell; say to General Stuart he must do what he thinks best.'” This response removed Jackson from directly influencing or advising for the rest of the battle of Chancellorsville.

Second, Jackson’s memory influenced his troops on May 3. General Stuart rallied soldiers of Jackson’s corps by encouraging them to charge and remember “Stonewall.” Arguably, Stuart could have done the same if Jackson was alive or dead, and it probably would have had the same result.

Third, Jackson and Lee communicated by written messages in the days between his wounding and death, but again, Jackson did not influence military matters directly. The communication was more influential for later evaluating these generals’ military relationship than for influencing battlefield events.

At this point, I’m of the opinion that—militarily—it wouldn’t have made a significant difference if Jackson had died on the battlefield on May 2. He does not seem have influenced the leadership transition, offered concrete advice for the battle, inspired the soldiers because he was still alive, or impacted Lee. An argument can be made that if Jackson had died, there could have been a wave of sadness or despair in the the troops and for Lee…but it could also be argued that it would have had a revenge factor, too.

There is more to a life-story than military matters, though.

The days between Jackson’s wounding and death made the difference to him and to his family. If he had died on the battlefield, there would have been no chance to say good-bye to his wife and baby daughter. Instead, he was able to see his loved ones again and eventually to religiously prepare for death—something he had always wanted as part of his “good death” desire. Once Jackson had been told he was dying, he gave brief directions and advice to his wife about his funeral, burial, and what she should do when he was gone. That interaction, as sorrowful as it was, eventually became an important part of his wife’s memories and part of her closure.

I think an argument can be made that militarily Jackson was out of action and out of influence when he was wounded on May 2. But because he lived until May 10, he got to see his family again and he had a good death with his faith and hope for eternity central in that last experience—something that would have been less possible if he had died quickly after his wounding at Chancellorsville. The eight days mattered, even if they did not change the military situation.

Sources:

Hunter Holmes McGuire, Wounding and Death of Jackson

James I. Robertson, Stonewall Jackson: The Man, The Soldier, The Legend, (New York, Macmillan, 1997).

Robert Lewis Dabney, Life and Campaigns of Lieutenant General Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson, Reprinted, (Harrisonburg, Sprinkle Publications, 1983).

Mary Anna Jackson, Memoirs of Stonewall Jackson (1895).

Well, Jackson’s thought processes might have been impacted, but he did have the presence of mind to recognize that impact, and his ‘advice’ to Stuart “do your best” is evidence of that, at least to me. And as pointed out, at least he did get say “goodbye” to his wife and daughter and others.

Great article here..

An interesting medical paper on the cause of Jackson’s death can be found at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22479920/.

Nice. Could it be that Yankee artillery caused the death of former VMI artillery instructor Jackson, since artillery fire was what caused his litter bearers to drop him rather rudely.

Good point about the artillery. Ironic.