Ewell’s Letter to Grant in the Wake of Lincoln’s Death

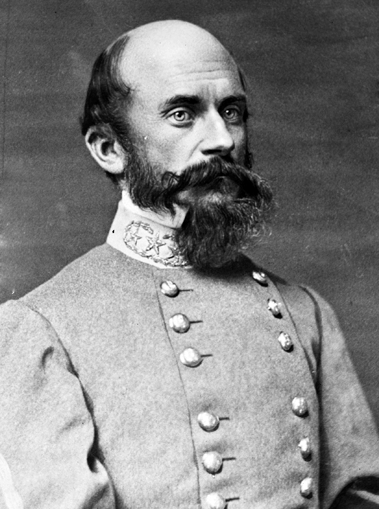

Shortly after his capture at the battle of Sailor’s Creek during Lee’s flight from Petersburg and Richmond, Lt. Gen. Richard Stoddert Ewell was sent to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor for incarceration. En route, he and fellow prisoners stopped briefly in Washington on April 14, and then set out by train for New York.

While on the Jersey Ferry, Ewell ran into Union Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler, by coincidence a fellow passenger.[1] Butler shared the stunning news that President Lincoln had been gunned down in Ford’s Theater the previous evening—just hours, in fact, after Ewell’s party had left the capital. “My God!” Ewell exclaimed. “I am sorry for that; it is the worst thing that could happen to the South.”[2]

Later that morning, when he heard news of Lincoln’s death, Ewell wept.

The party reached Boston at 5:00 p.m. and Fort Warren at 6:30 after a trip fraught with danger. Vengeful crowds along the route had harassed them and demanded they be hung.[3]

Agitated by the news and the angry mobs, Ewell took up pen to write—soldier to soldier—to Union general in chief Ulysses S. Grant. I came across this today while researching something else and thought it worth sharing. I’ve kept the original punctuation but have added a paragraph break for clarity:

Fort Warren, April 16, 1865.[4]

Lieut. Gen. U. S. Grant,

Commanding U. S. Army: General:

You will appreciate, I am sure, the sentiment which prompts me to drop you these lines. Of all the misfortunes which could befall the Southern people, or any Southern man, by far the greatest, in my judgment, would be the prevalence of the idea that they could entertain any other than feelings of unqualified abhorrence and indignation for the assassination of the President of the United States, and the attempt to assassinate the Secretary of State. No language can adequately express the shock produced upon myself, in common with all the other general officers confined here with me, by the occurrence of this appalling crime, and by the seeming tendency in the public mind to connect the South and Southern men with it. Need we say that we are not assassins, nor the allies of assassins, be they from the North or from the South, and that coming as we do from most of the States of the South we would be ashamed of our own people, were we not assured that they will reprobate this crime.

Under the circumstances I could not refrain from some expression of my feelings. I thus utter them to a soldier who will comprehend them. The following officers, Maj. Gens. Ed. Johnson, of Virginia, and Kershaw, of South Carolina; Brigadier-Generals Barton, Corse, Hunton, and Jones, of Virginia; Du Bose, Simms, and H. E. Jackson, of Georgia; Frazer, of Alabama; Smith and Gordon, of Tennessee; Cabell, of Arkansas, and Marmaduke, of Missouri, and Commodore Tucker, of Virginia, all heartily concur with me in what I have said.[5]

Respectfully, .general,

R. S. EWELL,

Lieutenant-General, C. S. Army.

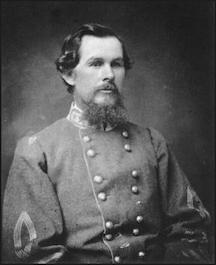

Hunton later professed to violently disagree with the decision to send the letter, although no contemporaneous record of his dissent exists. Only later, in 1904 in a private autobiography he dictated to his family when he was 82, did Hunton register his complaint. “I was very much excited about it, and opposed to it with all my might,” he said, claiming several others came to his aid in the argument. Overruled, Hunton grew nasty. “I asked General Ewell where the leg he lost at Second Manassas was buried; that I wished to pay honor to that leg, for I had none to pay to the rest of his body.”[6] Ewell said he did not know.

I suspect he had much else on his mind: capture, incarceration, assassination, and questions about his own fate. The war was coming to an end, which would have brought uncertainty under even the best conditions; Lincoln’s murder in the midst of that turned everything upside down and inside out.

Imagine how he felt, with an enraged Northern populace seeking retribution for an “appalling crime,” uncertain what would happen to him, far from home in a desolate fort in the middle of Boston Harbor. It’s little wonder he sought the solidarity of his fellow officers—those around him and even one he fought against.

————

[1] Eppa Hunton, Autobiography of Eppa Hunton, Eppa Hunton, Jr., ed. (Richmond: William Byrd Press, 1933), 130.

[2] Donald C. Pfanz, Richard S. Ewell: A Soldier’s Life (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1998), 447.

[3] For details, see Pfanz 447-8. It’s a cool story!

[4] The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. (Washington, DC; Government Printing Office, 1880-1901), v. 46, Part 3, 787.

[5] That list of officers, in alphabetical order:

Seth M. Barton

William L. Cabell

Montgomery D. Corse

Dudley M. DuBose

John W. Frazer

George W. Gordon

Eppa Hunton

Henry R. Jackson

Edward “Allegheny” Johnson

John R. Jones

Joseph Kershaw

John S. Marmaduke

James P. Simms

Thomas B. Smith

John R. Tucker

[6] Hunton, 137-8.

Henry R. Jackson, Edward Johnson, and Thomas B. Smith were all captured at Nashville. I wonder how Smith felt, who was beaten after his capture, which led him to go mad in later years.

IIRC, Smith was not just “beaten,” he was brutalized with the business side of a sabre upon his head. Whatever one’s inclination in this fratricidal war—and all my inclinations are colored blue—this was totally unwarranted.

The appendix on Smith in your Nashville book, “They Came Only to Die,” was fascinating.

God, we lucked out. It’s a miracle that the aftermath of April 1865 did not include widespread slaughter and retribution. It is also a tribute to the people of this country, from all backgrounds and regions, that things turned out the way they did. I don’t know what Ewell’s motivations were, but I applaud his sentiments. I realize that things were not perfect and that basic civil rights were denied another century, but maybe we are too tough on the people in the post war period. They knew how close things came to totally melting down.

Ewell saw firsthand how angry northerners were by the news of Lincoln’s assassination. He knew how quickly things could have turned ugly because that ugliness dogged his train all the way to Boston.

How like you to take Ewell’s sincere expression of shock and regret over the loss of Lincoln by heinous murder, and his commendable effort to reassure Grant that neither he nor any Southerners were in accord with that action, and drip snark all over it, accusing Ewell of simple selfish self-interest. It is a fact that the South knew that Stanton and others were already planning a hard landing for the South, and that Lincoln opposed that, but Ewell was without question reacting as a human and as a military figure for whom the assassination existed far outside the code of honorable conduct, and communicating that to another military figure who would understand that sentiment. Had he just been seeking cover, he would have sent the letter to Johnson.

Agreed with the miracle and agreed with Ewell reacting as a man. These guys were men who took the gentlemanly code of honor seriously. It’s not clear if BG Hunton objected to sending it for the reason of appearance of obsequiousness but based on a code of honor that may well be why. These are men who saw death in the face, men who had close calls with many a bullet.

This is a brilliant exchange….many. thanks.