On the 160th Anniversary of West Virginia’s Statehood

If people still remember poet Vachel Lindsay today, it’s because they saw Dead Poet’s Society way back when and remember the lively scene when the students all start chanting lines from his poem “The Congo” (and if you didn’t, you can see it here).

Lindsay popped up on my radar screen this week for an entirely different reason this week, though, thanks to a stop in Charleston, West Virginia.

My family and I were driving to Illinois—“the Land of Lincoln,” as they’re fond of calling it. Our route would take us on I-64 from Virginia into West Virginia, across Kentucky and southern Indiana, and then into southern Illinois. It wasn’t a specifically a Lincoln trip, per se, but Kentucky was Lincoln’s birthplace; our route took us within a couple miles of Lincoln’s boyhood home in Lincoln City, Indiana; and then into Illinois itself.

But I ran into Lincoln in Charleston, on the grounds of the West Virginia state capitol. I had actually stopped to get a photo of the Stonewall Jackson statue that still stands on the capitol grounds. Booker T. Washington, who grew up in West Virginia, has a bust on the capitol grounds, too.

Lincoln stands front and center of the building, though. I was, at first, surprised to see him. To my knowledge, Lincoln had never spent time in West Virginia, even when it was still part of Virginia.

More surprising, Lincoln was covered in cloak or shroud. His face is cast downward, looking not at the ground but inward, introspectively. The statue does not depict an inspiration or authoritative Lincoln. This is a man deep in his own thoughts.

The statue dates to 1974, dedicated on June 20 of that year by Governor Arch A. Moore. The sculptor, Fred Martin Torrey, had been born in Fairmont, West Virginia, in 1884, but he died in 1967 and never got to see his creation installed in front of the capitol.

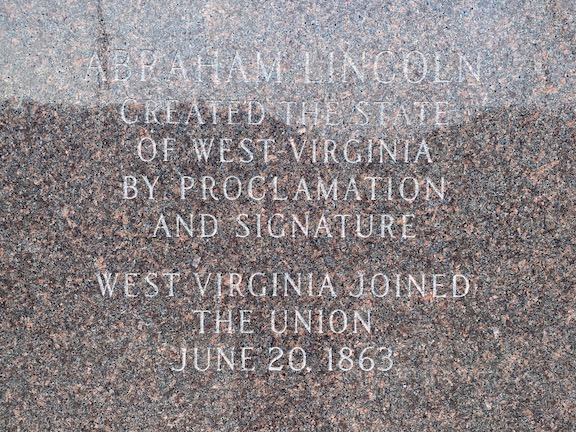

And of course, that’s why the statue was there: West Virginia owes its creation to Lincoln. The state was formally founded on June 20, 1863, created from loyalist counties that essentially decided to secede from seceded Virginia. Early war victories secured the territory for the Federal government, paving the way for the political change.

But as Torrey’s statue reminds us, statehood wasn’t necessarily smooth or simple, for the state or for Lincoln.

Torrey based his depiction of Lincoln on a poem by Vachel Lindsay, “Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight.” Lindsay writes of “A bronzed, lank man,” depicted literally in the bronze statue. Lincoln, of poem and sculpture, wrestles with the troubles that result from war, carrying “on his shawl-wrapped shoulders now/The bitterness, the folly and the pain.”

Lindsay, too, wrestled with the troubles of war. Written in 1914, “Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight” projects Lindsay’s concerns about the early war in Europe—World War I—onto a figure Lindsay knew well. Lindsay was born in 1879 in Springfield, Illinois, in a house once own by members of Lincoln’s family, so the young poet was steeped in Lincoln culture not just because of Lincoln’s stature as of one of the greatest Americans but as a neighbor. He could easily envision Lincoln walking the streets of their hometown in the wee hours of the morning just as Lincoln must have walked the halls of the executive mansion or stalked the streets between there and the War Department. Indeed, Lincoln moves much like a ghost in the piece—one Lindsay must have thought about deeply as a young man and as an older poet.

It was an interesting choice to place the statue of Lincoln walking at midnight in front of the state house in Charleston. It juxtaposed the idea of a deeply troubled Lincoln with the notion of West Virginia statehood. Statehood for Virginia’s westernmost counties offered several political advantages—but peeled away loyalist counties from the rabblerousing Virginia was also a morally challenging moment. To hobble the proud Virginia by stripping it of territory was a lasting slap in the face of rebellion, but it ensured hard feelings would linger after the war’s end, too. On the other hand, should loyal Americans be forced to secede from the country because other counties had voted to do so? Lincoln grappled with these questions in the midst of war, with men from the territory fighting for both sides.

Importantly, Lindsay’s poem on which the statue was based was written in present tense. Lincoln’s struggle remained immediate for Lindsay in a similar time of war, and the present tense underscored the immediacy of that connection. Lindsay invited his readers to feel the worry and the weight:

He is among us:—as in times before!

And we who toss and lie awake for long

Breathe deep, and start, to see him pass the door.

And we can see, those who look at the statue today, that Lincoln’s is among us, in bronze if not in person, troubled, human, invested deeply in the process. And if we read the poem, he remains with us, too, “as in times before!” The connection remains timeless.

The statue’s presence in front of the state house—this particular Lincoln, not a monolithic, inspiring, larger-than-life Lincoln—is certainly a call to action for lawmakers who should likewise walk at midnight and consider the weight of their responsibility and the trust placed on them. They must remember Lincoln’s example: consider weighty matters with the gravity they deserve. Acknowledge responsibility. Do the right, not just the easy. Be invested, deeply, in the process. Consider.

But this is a call to all of us, too, as a self-governing people. We must feel the weight. We must do right, not just easy. We must walk at midnight, searching for answers, looking for the way.

————

You can read Lindsay’s poem here.

“But this is a call to all of us, too, as a self-governing people.”

This is the problem of West Virginia history. It was not the result of a “self-governing people”. It was created in the midst of a civil war in which the electorate was at war within itself. The state was created by a body of self-appointed men who later held elections but only for their supporters. It was the only state where there was no choice for the highest offices. As Charles Ambler said, “There was no denying the fact that West Virginian was largely a creation of the Northern Panhandle and of counties along the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad…”. Even officials of the Unionist Restored Government recognized the unfairness of creating a new state in the midst of a war. Lt. Gov. Daniel Polsley said on August 16- “If they proceeded now to direct a division ofthe State before a free expression of the people could be had, they would do a more despotic act than any ever done by the Richmond [Secession] Convention itself”.

It is time we used more discernment in discussing the creation of the state. It was not a band of brothers by any means, as shown by the words of a delegate to the constitutional convention, referring to the secessionist counties included in the new state. Peter van Winkle, Dec. 17, 1861- “Well, sir, if these counties are inhabited by secessionists, some disposition has got to be made of them. They must be, as some remarks made by gentlemen here seem to point to – they must be exterminated by exile or death, or remain where they are. But in either case, sir, we want the territory. If they are going to remain upon it, still we want it.”

The irony of the admission of West Virginia is that it entered the Union as a slave state.

Sure, but subject to the Willey amendment. Meanwhile the dispute of Virginia v West Virginia of 1871 remains of at least academic interest (if not practical).