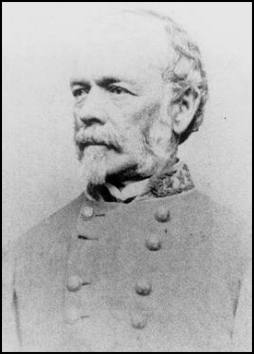

Joseph E. Johnston as a Commander

ECW welcomes guest author Greg Thiele

The most important principle of command is that the commander is responsible for everything which happens or fails to happen — good or bad — in his or her command. It seems Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston either never learned this or sought to evade the judgment of historians by denying responsibility at every turn. Even a casual reading of his memoirs reveals that Johnston was never culpable for failure and, in fact, disaster occurred largely because the Confederate government ignored his repeated warnings.

Johnston’s judgment is open to question. During the battle of Seven Pines, while his right wing was supposed to go into battle, Johnston decided to position himself on the left wing to watch for Federal reinforcements crossing the Chickahominy. Rather than position himself at the critical point where action was to occur, Johnston intentionally placed himself where he could not easily influence the course of the battle and instead decided to take position to accomplish a task any subaltern could have managed. Is it any wonder Seven Pines turned into a fiasco?

Johnston indicated Seven Pines would have been a Confederate victory if he had been able to finish the battle. Near dusk on May 31, 1862, at the end of the day’s fighting, Johnston was wounded and relinquished command of the army. He indicated in his memoirs that he wanted to continue the battle the next day, but his wounds meant little effective fighting occurred. Johnston went on to claim that circumstances favored the Confederates who could have won a decisive victory – had he not been wounded.

After he convalesced from his injuries, Johnston’s next opportunity came during the Vicksburg campaign. On the last day of April 1863, U. S. Grant crossed his army from the Mississippi River’s west bank to the east bank. Grant immediately set off inland toward Jackson to cut Vicksburg’s communications. Johnston arrived in Jackson just before Grant’s army. With the small force under his command, Johnston was unable to halt Grant’s advance. He wired to Richmond, “I am too late.” After capturing Jackson, Grant turned west, attacked John Pemberton’s army, and forced it to retreat into the Vicksburg fortifications. Vicksburg was besieged for more than 40 days. Johnston took no action to raise the siege until late June. He spent several days in what seems to have been a leisurely reconnaissance of the Federal outer line when he heard that Vicksburg had surrendered, whereupon Johnston withdrew to Jackson.

In the belief he had no other option and against his better judgment, Jefferson Davis gave Johnston command of the Army of Tennessee for the 1864 spring campaign. After winning a bloody victory at Chickamauga, the Army of Tennessee had suffered a humiliating defeat at Chattanooga in late November 1863. Johnston assumed command and did a creditable job of preparing the army for the coming campaign. Once the campaign began, he never stopped retreating. By stages, the Army of Tennessee withdrew from north Georgia to the outskirts of Atlanta. With the fate of Atlanta hanging in the balance, the Confederate government wished to know Johnston’s plans to deliver the city from the advancing Union army.

Johnston was sacked because he offered no plan to defend Atlanta. In his memoirs published in 1874, Johnston asserted he was waiting for the strung-out Union forces to cross the Chattahoochee River. With the river as an obstacle, Johnston could attack a portion of the Union army and defeat it in detail. Due to the fleeting nature of such an opportunity, Johnston’s plan would have been difficult to carry out. Success would have required timely intelligence and a rapid transition from defense to attack. There is no reason to believe Johnston could manage such a feat.

Although Johnston’s memoirs asserted he had a plan to deliver Atlanta, there is no contemporary evidence of this. Johnston claims he shared his plans with his successor, John Bell Hood, before leaving the army. In Hood’s recounting, Johnston left the army without revealing anything of his plans.

Johnston received another opportunity to command in the war’s closing days. When Robert E. Lee was appointed Confederate general-in-chief in February 1865, he requested Johnston’s assignment to command Confederate troops resisting William T. Sherman’s advance through the Carolinas. By this time, Confederate defeat was only a matter of time regardless of who was in command. Johnston surrendered his army at the Bennett Place on April 26, 1865.

Joseph E. Johnston held important commands at several critical moments during the Civil War, and each time his generalship was found wanting. While his supporters and admirers – and Johnston himself – might blame wounds, injury, the Confederate government, or Jefferson Davis for Johnston’s inability to win victories, these are nothing more than excuses. Commanders are expected to get results, and they must bear responsibility for victory or defeat. Johnston was never willing to accept this. When examined in this light, it is a relatively simple matter to judge Johnston’s Confederate army career. For all Johnston’s positive leadership qualities, for all the hopes he and others may have had and the expectations of great results he could deliver, Johnston was a failure as a general.

Greg Thiele is a retired Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel. He commanded infantry units up to battalion level.

Good article. I have never fully understood the Joe Johnston bandwagon.

If you want a very deep and unique view of the first half of Johnston’s Civil War career, I highly recommend the recently released “The Civil Wars of General Joseph E. Johnston, Confederate States Army: Volume 1: Virginia and Mississippi, 1861-1863,” by one of the war’s deans, Richard M. McMurry. https://tinyurl.com/4uvdjf3t

Can’t really disagree with this assessment when looking at Johnston’s Civil War in toto.

Your opening paragraph, well describes Johnston’s penchant for avoidance of responsibility. The sentence “It seems Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston either never learned this or sought to evade the judgment of historians by denying responsibility at every turn.” I have doubt that Johnston never learned about command responsibility but he has left a clear trail of evidence of his seeking to avoid responsibility at every turn.

Regarding Seven Pines, Johnston has proffered three accounts of his involvement in this battle. Each of his accounts varies with the facts and each assigns the culpability for failure to Gustavus Smith and Benjamin Huger. Two of his later accounts add Robert E. Lee into the mix of those culpable for the failure at Seven Pines. Charles Marshall maintained that Johnston employed the use of a deceptive “agility” with his use of facts regarding his explanation of the battle. It is inescapable that Johnston’s actions throughout May 31, 1862 were, at best, indecisive. For all intents and purposes, the window of opportunity for Confederate victory at Seven Pines ended well before his wounding at Fair Oaks.

Johnston has successfully managed to escape the scrutiny of historians for his failure at Seven Pines. Worse, Johnston’s assignment of blame to others has exonerated James Longstreet’s actions as being ‘a misunderstanding’ of Johnston’s orders. The development of the ‘misunderstanding’ myth was nothing more than Johnston covering up his and Longstreet’s failure to have completely overwhelmed Erasmus Keyes’s exposed IV Corps. As Marshall claimed, Johnston’s use of factual “agility” has successfully shielded his massive failure in command at Seven Pines.

Keyes, George Mindil, and other Federal combatants have described how Johnston’s plan should have resulted in the complete destruction of two of McClellan’s corps positioned south of the Chickahominy. One can only imagine the impact that such a decisive victory would have played on the 1862 political climate and the administrations of Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis.

Thanks for that analysis. In addition, I’ve always found an inherent problem in that – at least according to Johnston’s article in B&L Vol. 2 – this complicated attack was only slapped together after a recon on the morning of May 30 (less than 24 hours in advance) and then the complex command arrangements were the subject of verbal orders. That is a recipe for failure.

If anything the author is too kind to Johnston. Joe was about as cautious as McClellan. Like Little Mac, he hosted opposition politicians at his HQ. And like Little Mac, he was quite popular with the rank and file. Although I can see troops being nostalgic for his leadership after a little while under Hood.

Thank you for these insights. He didn’t listen to good advice when it came to Sherman’s funeral.

Johnston could have helped at Vicksburg and did not. He, like Bragg, taught his soldiers how to lose. Unlike Lee who fought despite being outnumbered, he always cowered at any number of Federal troops larger in number to his.

Do you have a source on the “I am too late” message? I can’t seem to find it in the OR