BookChat: Stolen by Rosemary Nichols

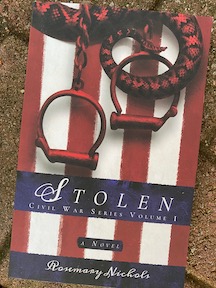

I had the opportunity recently to chat with ECW’s good friend Rosemary Nichols about her historical novel Stolen (Atmosphere, 2021). Stolen tells the 1860 tale of two Northern girls, on their way to college, who are kidnapped into slavery. “Lincoln has been elected. Southern states are seceding,” the book jacket says. “For Northerners, the streets of New Orleans and its courts are now unfriendly places.”

I had the opportunity recently to chat with ECW’s good friend Rosemary Nichols about her historical novel Stolen (Atmosphere, 2021). Stolen tells the 1860 tale of two Northern girls, on their way to college, who are kidnapped into slavery. “Lincoln has been elected. Southern states are seceding,” the book jacket says. “For Northerners, the streets of New Orleans and its courts are now unfriendly places.”

A retired attorney, Rosemary is active with the Capital District Civil War Roundtable in greater Albany, NY.

What is the premise of Stolen?

Even privileged black Northerners were not safe from kidnapping under the umbrella of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. The only way for families to rescue their stolen children was to go where they were being held and steal them back. This situation became more dangerous in the months immediately preceding the Civil War.

How does the book reflect your own personal interests in the Civil War?

I have been studying various aspects of the Civil War since I was in high school. In the summer between my junior and senior years in high school, I decided to write the Great American Civil War novel. I had been inspired by success in a High School Historian contest sponsored by the Arizona Historical Association to believe I might be able to write. There was, however, not much good research material or references available in a small city (Prescott) in central Arizona in the mid-1960s.

Fortunately, I got distracted from that overly ambitious authorial goal. Regularly thereafter, all through college, graduate school, and law school I kept reading and thinking about the Civil War. It has so many aspects and was so transformative of American culture in almost innumerable ways.

My particular areas of interest include the impact of the war upon families, especially the home front North and South. How women and children dealt with the war has always been an interest. I have also studied the impact of various pieces of federal and state legislation on the citizens of color in New York immediately before and during the Civil War.

Nineteenth century technology is an abiding interest. I have been fortunate for decades to be a volunteer lawyer and sometime board member for the Hudson Mohawk Industrial Gateway in Troy, the celebrant and custodian of much of the physical evidence that supports the claim that the Capital Region of New York was the Silicon Valley of the 19th Century.

It was no accident I set a significant part of Stolen in New Orleans. It is one of my favorite cities and I welcomed an opportunity to study it during the Nineteenth Century.

The book covers aspects of the Civil War other authors seldom consider. What are some of those areas you illustrate?

One area of interest is the relatively primitive law enforcement system that is available to aid families in the uncomfortable position of the Van der Peysters. It demonstrates that, even for families of means, self-help can be the only option to save family members who have been kidnapped into slavery.

The extent to which certain women were empowered with their own agency is accurate. Mrs. Willard’s School, a fine girls school in Troy in the 19th Century, still thriving into the 21st, produced generations of women like the Van der Peysters who were educated in the same subjects and to the same extent as their normally more privileged male peers.

That quality of education makes a huge difference in the lives of the students then and now. I wanted to celebrate that early educational triumph.

Trains and steamboats are no longer the important elements in American transportation they were in the 19th Century. I wanted to share those systems working in 1860.

I wanted to show the casual racism that was such a part of American life in the 1860s, whether that life was lived in the North or the South. A corollary of that racism is the extent to which persons of color were viewed not as people but simply as the solution to financial difficulties without any regard for their humanity. That will be an ongoing theme in the Civil War books I hope to write in the years ahead.

There were Southern plantation owners who came to believe slavery was morally and legally wrong. Etienne and Sarah LeBlanc were my vehicle for exploring that truth. Tending toward realism, I also wanted to give some preliminary hint of the difficulties in removing an entire community of enslaved people to freedom in the North. That challenge will be more thoroughly explored in a next planned series book, Fleeing North.

The extraordinary isolation that was typical of a 19th century plantation has been regularly referenced in scholarship on the plantation South. I wanted to show how that emotional and physical remoteness operated in reality. The people at Magnolia Ridge, most of whom were born, lived and expected to die in their home, are dangerously naive.

To avoid legitimate charges of being a Pollyanna, I felt I needed to show the ugly side of slavery. In addition to writing about Carl and Hannah’s experience in captivity, I did that through an accurate description of the Saturday afternoon slave auction in the Rotunda of the St. Charles Hotel. I also used the hideous expectations of Andre LeBlanc for the “initiation” of enslaved Rebecca by his friend Joseph. Of course, as Aunt Hat says, no child is going to be debauched in a house where she is resident. Oh, the wonder of a well-educated, well-to-do confident Northern matron.

The plot covers ground from Cleveland to New Orleans. How did you go about researching the locales in the book?

Many of the locales I knew in their modern form. I’ve mentioned earlier my love for New Orleans. New York City is two and a half hours by a comfortable train from the Capital District. Cleveland I have had a glancing experience with. I know its near neighbor Oberlin much better. It’s a great heritage visit for anyone interested in 19th century civil disobedience or the Underground Railroad.

When I could, I used an existing building or place. That made my research so much easier. If I didn’t have that benefit, I took advantage of the resources of every writer of historical fiction: the Internet and library archives.

Part of the pleasure of including Louisiana in a work of historical fiction is that so many rich sources are still existent. Some of those places include my plantation, Magnolia Ridge, closely modeled physically on Magnolia Mound in Baton Rouge. That property has been very closely studied. If you were able to walk upstairs at Magnolia Mound, you could stand in the room that Ameranda and her sister Sarah occupied while in Louisiana. I had detailed architectural information, including an Historic American Building Survey report for that property, that allowed that level of precision.

The house in New Orleans where Carl and Hannah are imprisoned exists. It is the Hermann-Grima house museum in the French Quarter. Contemporary images of Cafe’ du Monde look much as that historic property did in 1860, as does the general area around Jackson Square.

I was able to choose two famous steamships, the Star of the West and the Natchez VI, to transport my family to and fro in their rescue mission. The Star is known to even casual students of the Civil War. It did not survive. After being captured by Confederate forces, it was scuttled in defense of Vicksburg in 1863. But it was the very prominent, well-discussed and frequently illustrated personal ship created by Commodore Vanderbilt. The glory days of the Star were behind it in 1860, but its interior and amenities had not much changed.

A later incarnation of the Natchez VI, current IX, is a prominent New Orleans tourist attraction. You can spend part of a day or an evening with dinner and a jazz band, traveling the Mississippi River as if it were the 19th Century.

Unfortunately, the hotels I referenced in Stolen, Cleveland’s Weddell House, the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City, and the St. Charles in New Orleans no longer exist in our world. They are all well represented in images and writing from the 19th Century and later. These hotels were important destinations for travelers throughout the properties long and storied careers. They were remembered in detail in travelogues and letters.

Where did the idea for the book—and the intended series—come from? What inspired you to write about this?

Ameranda Van der Peyster and I have been keeping company in my head for at least a quarter of a century. It is not an accident that Ama and I share a birthday exactly a century apart. I was curious what the life of a girl (becoming a young woman) exactly my age would have been.

It quickly became apparent that to have the kind of Civil War-influenced life I wished to explore, Ama could not be a girl of modest means raised on the Arizona frontier in the 19th century. I already knew what that life was like. I lived it growing up.

Living in the Hudson River area of upstate New York, the Knickerbockers—the original Dutch settlers and their descendants—were prominent in colonial and earlier history. As the distinguished New Netherland Institute, headquartered in Albany, NY, has demonstrated in scholarly detail, the lives of Dutch inhabitants of what became New York (first colony, then state) who adapted to being surrendered to the English Navy without a shot fired.

Where do things stand with volume 2?

The plotting is well along. I encountered a timely distraction and put that book behind another that I am working to have available in book stores and online for the end of this year.

One of the recent Emerging Civil War publications is an engaging look at John Brown’s Raid: Harpers Ferry and the Coming of the Civil War, October 16-18, 1859, written by Kevin R. Pawlak and Jon-Erik M. Gilot.

At the same time I read that book, I also got a copy of a fine work, The Tie That Bound Us: The Women of John Brown’s Family and the Legacy of Radical Abolitionism, written by Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz and published by Cornell Press in 2013. I presume this book is a reworking of Ms. Laughlin-Schultz’ dissertation, but it is fine, readable history of the kind I most enjoy. The end notes and bibliography occupy almost as many pages in the book as does the main text.

Armed with those two books, I was temporarily distracted from a laboring steamboat traveling north in the inclement and dangerous weather of December 1860 to cover the traumatic experience of John Brown’s female relatives during the famous raid and its aftermath.

I had the opportunity to participate recently in the annual Savas Beatie meet-up in Antietam and Gettysburg. Kevin was one of the Antietam presenters. When I asked him a couple of questions related to his current book—not his titled presentation, The Battle for Burnside Bridge—Kevin was not familiar with the Cornell Press book. He did want the title, and I suspect he has already ordered a copy from the usual sources.

Kevin and everyone else that weekend to whom I answered the question “What are you writing?” said some variant of, “I didn’t know there was anything written on that topic. I would buy that book.” Magic words for a writer of historic fiction.

As a novelist, what are some of the challenges you faced as you worked on this project?

One of the most important issues that arose as my editor was reviewing the book was that, in my haste to tell the segment of the story about the family’s rescue efforts, the kidnapped young people had fallen out of the narrative after they were stolen. This was serious.

When she brought this issue to my attention, I immediately considered and then easily wrote what is a major portion of the interior of the book. Adding two more feisty women who hated or despised the villain enriched the story in important ways. It was yet another illustration, if I needed one, for the importance of a good editor.

Civil War fiction can be such a fraught genre. In my experience, it’s either been really good or overly melodramatic and overly romanticized. What’s your take on the genre, and how do you hope your novel fits into that?

I absolutely agree. There are people writing well-crafted fiction that tells a narrative that has very little connection to what I know to be the credible historical record on the topic on which they are writing.

I have never done that and I won’t do it. Historical integrity is too important to me.

Every one of the four books I have written to date and every book I hope to write in the future has or will have a substantive author’s note at the end. One section is devoted to recommended readings from professional or avocational historians if people wish to dive further into the topic I am discussing. Another section, by far the longest, is where I fess up to what in the book is historical fact and where and how I have fudged the record.

In some ways the author’s note as I perceive it is the most important credibility building element in the book. I want people to trust me and be comfortable believing that what I am writing about and how I am presenting it is what I believe the historical record shows.

That is what I believe is the most important element in historical fiction. The contract between myself and my readers is “I will tell you a story that I hope you will enjoy. You will, if you choose to read the author’s note, know what I believe is true based on reasonable research.”

Is there something I didn’t ask that I should have?

Why, after a fifty-year career as a hard-working environmental lawyer, did you choose to venture in your presumably declining years into this fraught field?

Anyone who knows me knows that I love to tell stories. Writing them down gives me the prospect of a wider and over time deeper audience. If my books provide any pleasure, information or insight into a specific element in our history, then I will have achieved my goal.

How can people buy a copy of your book?

All four of the books I have published to this point are available at Amazon. Barnes and Noble has three of the books. (For some reason, the Erie Canal book is missing. I will fix that.)

——–

About Rosemary Nichols:

I grew up in central Arizona in the small city of Prescott and on a cattle ranch in the Kirkland Valley. Wanting to try my wings in a larger setting, when I graduated from high school, I persuaded my parents to let me attend college in another state. I was the first person in my family to go to college, I earned an undergraduate degree in American history and a master’s degree in American Constitutional History from the University of Washington in Seattle. Then I went to law school at the University of Chicago.

When I graduated from law school I took a two year contract at the State University of New York at Albany teaching environmental law and environmental ethics in the Business School. I was one of the creators of the earliest team-taught course in environmental impact assessment as part of an interdisciplinary Environmental Studies Program. Then I went to teach law school at the University of Pittsburgh for three years.

I returned to Albany and spent the decade of the ‘90s creating and running a not-for-profit foundation, the New York Land Institute, which specialized in consensus building on controversial land issues. Since then I have practiced law in every setting except a large firm: solo practitioner, member of a two person specialty firm, and partner in a small to medium sized law firm. I also served five years as the economic development director and director of planning for the small upstate New York municipality where I live. I retired to write historical fiction.

I come by my love of history legitimately. On my father’s side of my family, my ancestors came to the “New World” in the middle of the 17th century. They came, respectively, to a small village in Quebec (Nicolet) and a plantation in Virginia. My Canadian great-great grandfather migrated across the United States to California in the 1850s with his orphaned children, after surviving an exciting shipwreck off the coast of Baja California on his initial visit to California. His son, my great-grandfather, came to Arizona in 1873. The Nichols ancestors migrated from Tidewater Virginia to the Blue Ridge to Tennessee to Arkansas to Texas and finally in the 1870s to Tempe in the Valley of the Sun in Arizona.

My mother’s mother and father were part of a great migration in the early 20th century from Europe to the United States. They came in 1915 from Norway, moving through Ellis Island to Wisconsin to Idaho and then to Tacoma, Washington. My father was training as part of his service in the Navy during World War II and met my mother at Sand Point, Idaho. They married when the war ended and moved to Arizona.

I live in upstate New York in a small city (Watervliet) where the Erie Canal began. Watervliet was also the furthest upriver that Henry Hudson came on his initial exploration. The Cohoes Falls blocked the explorers from further travel upriver. Our only claim to fame is that we house the Watervliet Arsenal, providing products for the US military since 1813.

I co-authored a two book series for Calkins Creek, a Boyds Mills Press imprint. The series is called “Hidden History.” The first book in the series, Rory’s Promise, was published in September 2014. It is a fictionalized narrative of a disastrous Orphan Train project of the New York Sisters of Charity to two small copper mining towns in eastern Arizona in 1904.

The second book, Freedom’s Price, was published in October 2015. It is about Dred Scott’s daughters in 1849 in St. Louis. 1849 was a terrible year for St. Louis. It had a cholera epidemic and a major fire just as Dred Scott’s family was seeking their freedom from slavery. This book received the first of a new national award for writing.

As a solo author I finished the first book, Stolen, in a series on how the Civil War affects an upstate New York family of Dutch ancestry. Members of the family are stolen into slavery in New Orleans in the days just before the Civil War begins. The book describes the family’s efforts to rescue their relatives.

My second series celebrates the Building of the Erie Canal. It highlights the new technology that was created as part of the construction as well as the first location that came on line as the canal was created across New York State. The first book is set in Rome, NY, where the initial construction began.

I am also doing research on the destruction of the culture of the Plains Indians in the 1860s and 1870s, culminating in the Battle at the Little Big Horn. I intend also to cover the early days of the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pa.

My web address is rosemarygailnichols@gmail.com.

Abou

This is wonderful to see and read. Rosemary is a fantastic person with a tremendous background and knowledge base. I have two of her books and I am sad to say I have not yet read them in depth because of my crazy schedule (a publisher with little time to read–had I known that wad part of the deal, I might have chosen a different profession). Now I need to be more attention. Keep going, my dear. –Ted and Miss Kenya