How John Brown’s wife Mary ended up living in California and buried at Madronia Cemetery in Saratoga, Part I

Library of Congress

What’s a wife to do after her husband is hanged for treason?

Much has been written about the abolitionist work of John Brown, the part he played in the “Bleeding Kansas” border wars, and his disastrous raid on Harpers Ferry. His prophetic dying words anticipated the bloodshed of the Civil War, and his hanging outside of Charles Town, Virginia, and later burial in North Elba, New York, both sparked big headlines and drew large crowds.

Far less has been written about John Brown’s wife, Mary, and how she and his surviving children fared in the years after his death. So I was excited to come across several books recently, as well as some poems, that explore Mary’s story.

Reading John Brown’s Women, by Susan Higginbotham (2021), first sparked my interest in learning more about John Brown’s wife, Mary. While Higginbotham’s book is historical fiction, she incorporates plenty of historical details about the known actions of John Brown and his family. She also captures the likely concerns, insights, and emotions of the patient and persevering Mary, who has to say goodbye to her husband and sons time and time again as they go about what they believe to be God’s work. She also has to endure periods of extreme poverty and sickness and watch many of her children and stepchildren die young – of dysentery, consumption, whooping cough, accidental scalding, and other unknown causes.

In the Author’s Notes at the end of the book, Higginbotham writes: “Some time after John Brown’s death, an in-law of [his son] Salmon Brown visited North Elba, extolling the advantages of his new home, California. It made an impression. In 1864, Mary, her daughters, and Salmon and his family traveled by wagon train to that state, where Mary, Annie, Sarah, and Ellen spent the rest of their lives. Indeed, all of John Brown’s surviving children, except for John Jr., ended up migrating to California, although Salmon and his family later moved to Portland, Oregon, and Jason in his old age ultimately returned to Ohio” (1).

These words triggered a long dormant memory. Suddenly I recalled a walking tour I had gone on about 30 years ago designed to help our high school teaching staff learn more about the history of our community. It was then I first learned that Mary Brown and two of her daughters were buried at Madronia Cemetery in Saratoga, California, less than ten miles from my house in San Jose. At the time, this fact barely registered in my mind. Now, having become a Civil War aficionado, I wanted to know more.

How did Mary and her daughters end up here? What was her life like in the years following her husband’s death? Did she ever find a place of rest and a sense of peace? In looking for answers to these questions, the biography Miss Sarah Brown: Daughter of Abolitionist John Brown, written by Mary Miller Chiao, whom I met in the Santa Clara County Branch of the National League of American Pen Women, proved very helpful.

But first, some background. Mary Ann Day first came on the scene in John Brown’s life when he hired her older sister to serve as a housekeeper after his wife died. Mary tagged along to help with the housekeeping, spinning, and childcare, and John became attracted to her piety, work ethic, and compassion. They married in 1833 – Mary, 17, and John, a 33-year-old widower with seven children. She went on to give him thirteen more children, with seven dying in infancy, two (sons Watson and Oliver) dying at Harpers Ferry, and four (son Salmon and daughters Annie, Sarah, and Ellen) surviving after their father’s death.

Throughout the years of her marriage, Mary, a very devout woman, mostly stayed home – first in Pennsylvania, then Ohio, Massachusetts, and New York. Often pregnant, she took care of the various farms on which the family lived and raised the children, while husband John went off on his adventures, fundraising missions, quests, and raids. She also supported her husband’s work, despite the many sacrifices it entailed. Asked about this later, she said, “Does it seem as freedom were to gain or lose this? I have had thirteen children, and only four are left; but if I am to see the ruin of my house, I cannot but hope that Providence may bring out of it some benefit to the poor slaves” (2).

Frederick Douglass, who met the Browns in 1848, “wrote movingly of Mary’s participation in the Underground Railroad for people seeking freedom” (3). Abolitionist Gerrit Smith, in 1849, made an agreement with both John and Mary to live in the cooperative African American community of North Elba in the Adirondack Mountains, which he had financed, where they helped instruct free Blacks in how to cultivate crops and productively farm the land.

After her husband’s arrest, Mary journeyed to Harpers Ferry to see him one last time, and they dined together and talked over business before saying their final farewells. The next day, he was taken to the scaffold and hanged. As described in John Brown’s Raid: Harpers Ferry and the Coming of the Civil War, “Mary Brown’s trip through the North with her husband’s remains brought crowds of adorers and those interested in getting one last look at Brown’s earthly remains to the side of Brown’s coffin. Relic hunters turned opportunists; pieces of the rope and scaffold that hanged Brown turned into relics of Brown’s martyrdom” (4).

In a poem published in Prairie Schooner, author Veronica Golos imagines Mary’s perspective when describing the people gathering for John Brown’s funeral (6):

This morning they began to arrive. First one

in a small wagon, his young son

beside him. Then an entire

family, three children, father

mother, grandmother.

Even some we had

helped on to Canada. I stood

in my doorway, as the tract around the house

filled with horses, wagons, those who

had walked. Mr. Epps was nearby,

Mr. Riddick, silent as always.

I will not weep.

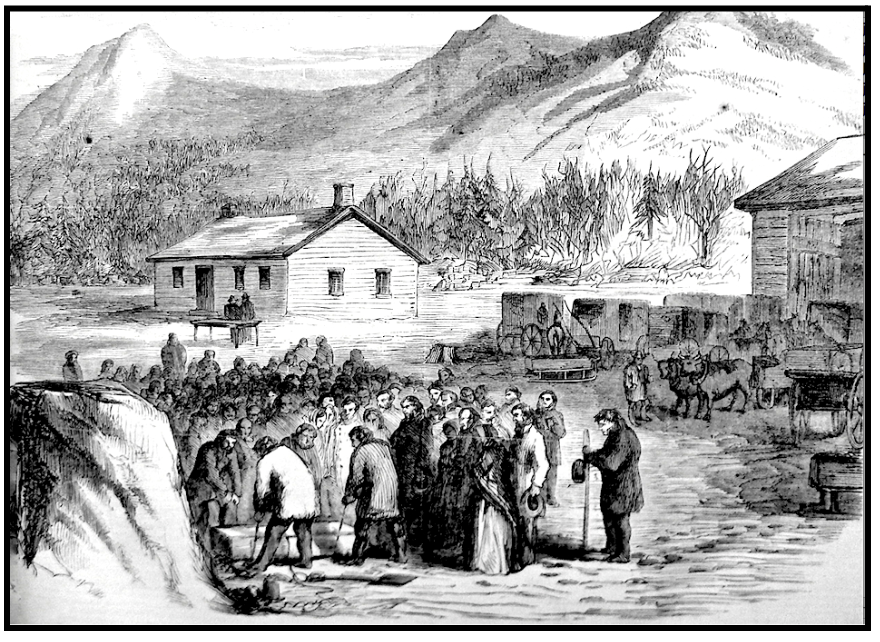

On December 8, 1859, John Brown’s body was laid to rest outside his farm in North Elba, New York. In the final pages of John Brown’s Women, after the crowds had departed, his family is struck by the quiet: “And then there was no one in the house but Mary, the four children left to her of the thirteen she had borne, Martha [the pregnant wife of Mary’s son Oliver], and Salmon’s wife Abbie. No reporters, no well-wishers, no neighbors. Just the Browns and the memories of the brave men who had left this place forever” (7).

Higginbotham, however, raises the question as to Mary’s “next steps” in her final paragraphs. Mary realizes “that while she was bereft, she was also her own woman. She had a paid-up farm, she had her health, and she was only in her forties. There were possibilities” (9).

Bonnie Laughlin Schultz, in the nonfiction The Tie That Bound Us: The Women of John Brown’s Family and the Legacy of Radical Abolitionism (2013), provides an answer. While initially Mary stayed in North Elba and sent her daughters Sarah and Annie to school in Concord, Massachusetts, as the Civil War kicked into gear “she decided to put aside John Brown’s jailhouse decree that she remain a permanent resident of Essex County to grasp for a better economic future in the West. In migrating, she also sought refuge from the curiosity and burdens associated with being both reviled and celebrated as John Brown’s kin” (10).

Son Salmon initially joined the Union Army in 1862, but due to his notoriety, officers drafted and signed a petition asking the Colonel to remove him from their regiment. Rather than cause trouble, Salmon chose to resign – then, in 1863, he decided to move with his family to California. Mary decided to join him (11).

Soon after, Mary, nine-year-old Ellen, and Salmon’s family left North Elba, traveling first to Iowa, where they were later joined by Mary’s daughters Sarah and Annie. After a cold winter in Iowa, they continued by wagon on the overland trail to California, where “Mary told her daughters they would create new lives and find better opportunities” (12).

The 2,000-mile journey presented its own dangers, as many of the troops that had previously manned the frontier garrisons, offering protection to travelers, had been transferred to the eastern Civil War battlefields. As a result, “Indians … became more bold … and [approximately 250] Sioux warriors infiltrated their wagon train,” but they left when members of the wagon train brandished their weapons (13).

Further dangers arose when it became known to other families in the wagon train that John Brown’s family was among them. Besides three of Salmon’s six Spanish Merino sheep being poisoned, the Browns learned of a plot to murder Salmon and perhaps the rest of the family. The New York Tribune on September 22, 1864, even reported: “There is a painful rumor, not yet confirmed … that they were pursued by Missouri guerrillas, captured, robbed, and murdered” (14).

Fortunately, it was only a rumor. The Browns “slipped away from that wagon train and eventually connected with another. Upon reaching the military post [in Soda Springs, Idaho] … they informed the authorities…. A detachment accompanied the Browns for nearly 200 miles until they were safely separated from those who would do them harm” (15).

Finally, in September 1864, the family arrived in Red Bluff, California – a town of about 2,000 people at the time, located on the Sacramento River. In a later account, Salmon’s wife, Abbie Hinckley Brown, said they arrived in Red Bluff “a hungry, almost barefoot, ragged lot,” but they found the people there generous and helpful in supplying their needs (16). “We were given a sack of flour and other groceries, and I was given a pair of shoes and cloth for a dress,” she recalled, and Salmon got a job right away “grubbing out young oaks for forty dollars. He did the job in eight days and we felt rich. How I loved California” (17).

Mary soon began working as a nurse and midwife; Sarah and Annie taught at “Colored” schools; and Salmon took up sheep-raising. In April 1865, Red Bluff’s citizens held a meeting “with the expressed purpose of raising funds for the purchasing and furnishing of a neat cottage for Mary A. Brown. The Red Bluff paper endorsed it and said, ‘If everyone who has hummed John Brown’s Body would throw in 10 cents, Brown’s family would have a home’” (18). Even the governor of California helped raise funds. By January 1866, the house was finished, and Mary moved into her new home, which still stands today.

Not everyone, though, was happy about the family of John Brown living among them. The vitriolic Red Bluff Sentinel’s news editor frequently attacked the Browns. Then, in 1869, arsonists burned down the Colored School. In 1870, the family decided to move to Rohnerville in Humboldt County, joined by Annie’s new husband, Samuel Adams.

There, Mary continued as a midwife, Sarah continued teaching, and Ellen married James Fablinger, a teacher from Illinois. However, while Salmon did well financially, the rest of the family did not. On top of that, “Rohnerville was cold, windy, and foggy, and James Fablinger was not robust, [so] in the winter of 1880, Mrs. Brown sent Sarah to look at the mountain property in Saratoga” that the family eventually purchased (20). Annie and Salmon and their families remained up north, but Mary, Sarah, and Ellen, James, and their three children packed their bags once again.

Check back for “Part II” to learn about the lives of the Browns and Fablingers in Saratoga, California, and their burials at Madronia Cemetery.

Endnotes:

- Higginbotham, Susan. John Brown’s Women: A Novel. Onslow Press, 2021, p. 391.

- “The Wives and Children of John Brown.” National Park Service, 17 April 2018, https://www.nps.gov/articles/wives-and-children-of-john-brown.htm.

- Libby, Jean. John Brown’s family in California : a journey by funeral train, covered wagon, through archives, to the Valley of Heart’s Delight : including the years 1833-1926, and honoring descendants of the women abolitionists of Santa Clara County, now known as Silicon Valley. Palo Alto, California: Allies for Freedom, 2006.

- Gilot, Jon-Erik M., and Kevin R. Pawlak. John Brown’s Raid: Harpers Ferry and the Coming of the Civil War, October 16-18, 1859. Savas Beatie, 2022, p. 121.

- “John Brown’s body.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Brown%27s_body#/media/File:John_Brown’s_burial.jpg.

- Golos, Veronica. “From The Lost Notebook of Mary Day Brown, Elba, New York, late evening, December 6, 1859.” Prairie Schooner, vol. 88 no. 4, 2014, p. 29. Project MUSE, https://doi.org/10.1353/psg.2014.0075.

- Higginbotham, Susan. John Brown’s Women: A Novel. Onslow Press, 2021, p. 389.

- Mwanner. “House at John Brown’s Farm. Wikipedia, 24 May 2008, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-kansas-city-times-mary-brown-overvie/13224826/.

- Higginbotham, Susan. John Brown’s Women: A Novel. Onslow Press, 2021, p. 389.

- Laughlin-Schultz, Bonnie. The Tie That Bound Us: The Women of John Brown’s Family and the Legacy of Radical Abolitionism. Cornell University Press, 2013, p. 91.

- “John Brown’s Family: A Living Legacy.” HistoryNet, 12 June 2006, https://www.historynet.com/john-browns-family-a-living-legacy/.

- Laughlin-Schultz, Bonnie. The Tie That Bound Us: The Women of John Brown’s Family and the Legacy of Radical Abolitionism. Cornell University Press, 2013, pg. 91.

- Damon G. Nalty. The Browns of Madronia. Saratoga, California: Saratoga Historical Foundation, 1996, pp. 9-10.

- “John Brown’s Family: A Living Legacy.” HistoryNet, 12 June 2006, https://www.historynet.com/john-browns-family-a-living-legacy/.

- Damon G. Nalty. The Browns of Madronia. Saratoga, California: Saratoga Historical Foundation, 1996, pp. 9-10.

- Sykes, Velma West. “Mrs. John Brown Shared Martyr Role from Afar.” The Kansas City Times, 26 Oct 1963, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-kansas-city-times-mary-brown-overvie/13224826/.

- “John Brown’s Family: A Living Legacy.” HistoryNet, 12 June 2006, https://www.historynet.com/john-browns-family-a-living-legacy/.

- Sykes, Velma West. “Mrs. John Brown Shared Martyr Role from Afar.” The Kansas City Times, 26 Oct 1963, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-kansas-city-times-mary-brown-overvie/13224826/.

- “California Historical Landmark #117: John Brown Home in Red Bluff, California.” NoeHill in San Francisco, 20 February 2011, https://noehill.com/tehama/cal0117.asp.

- Miller Chiao, Mary. Miss Sarah Brown. Mary Miller Chiao, 2022, p. 14.

Thank you for sharing this, how and why Mary is in Saratoga CA while John Brown is still moldering in North Elba, upstate NY.

I too lived in San Jose and Saratoga. Only to find out a couple of years ago at a July 4th service at St Lukes in nearby Los Gatos. Father Ernest Cockrell (retired rector of St Andrews Saratoga) was preaching with his US retrospective. He asked me to sub for a lector, a reading Fredrick Douglas. I bragged FD was commencement speaker at my alma mater, on the grounds of my high school in Hudson Ohio, which is next to the First Congregational church where John Brown made his proclamation. Earnest tells me about Madronia cemetery!! And now I learn from you that Mr Douglas was friends with the Browns. That makes sense and also reassuring that they were collaborating on the common cause.

Earlier that year. A former teacher published her book Pursuing John Brown. I had intended to read it during the week.

I visited Madronia and her marker and thought I helped to reunite the husband and wife in thought.

Tomorrow, I’m visiting Western Reserve Academy with my teacher and class mate. I’m in town to attend the memorial of a dear friend who had also walked that campus.

(And another thing, a fellow parishioner at St Luke’s has a cousin formerly on staff at WRA, campus in Hudson, OH!! It is indeed one small world.

Blessings for your work!

I’m just now seeing your comment – sorry for the long delay in replying.. Thanks for sharing all those interesting connections! I’ve been to St. Luke’s for several different events over the years. Maybe I’ll make it to North Elba or to the First Congregational Church in Ohio one of these years.

I just heard that I live on the Brown land in Rohnerville. The Brown house still stands. We live behind it on a lot that had some of the orchard. I always knew it was one of the oldest houses in the area, but had no idea of the connection to that famous Brown family.