Book Review: Wounded for Life: Seven Union Veterans of the Civil War

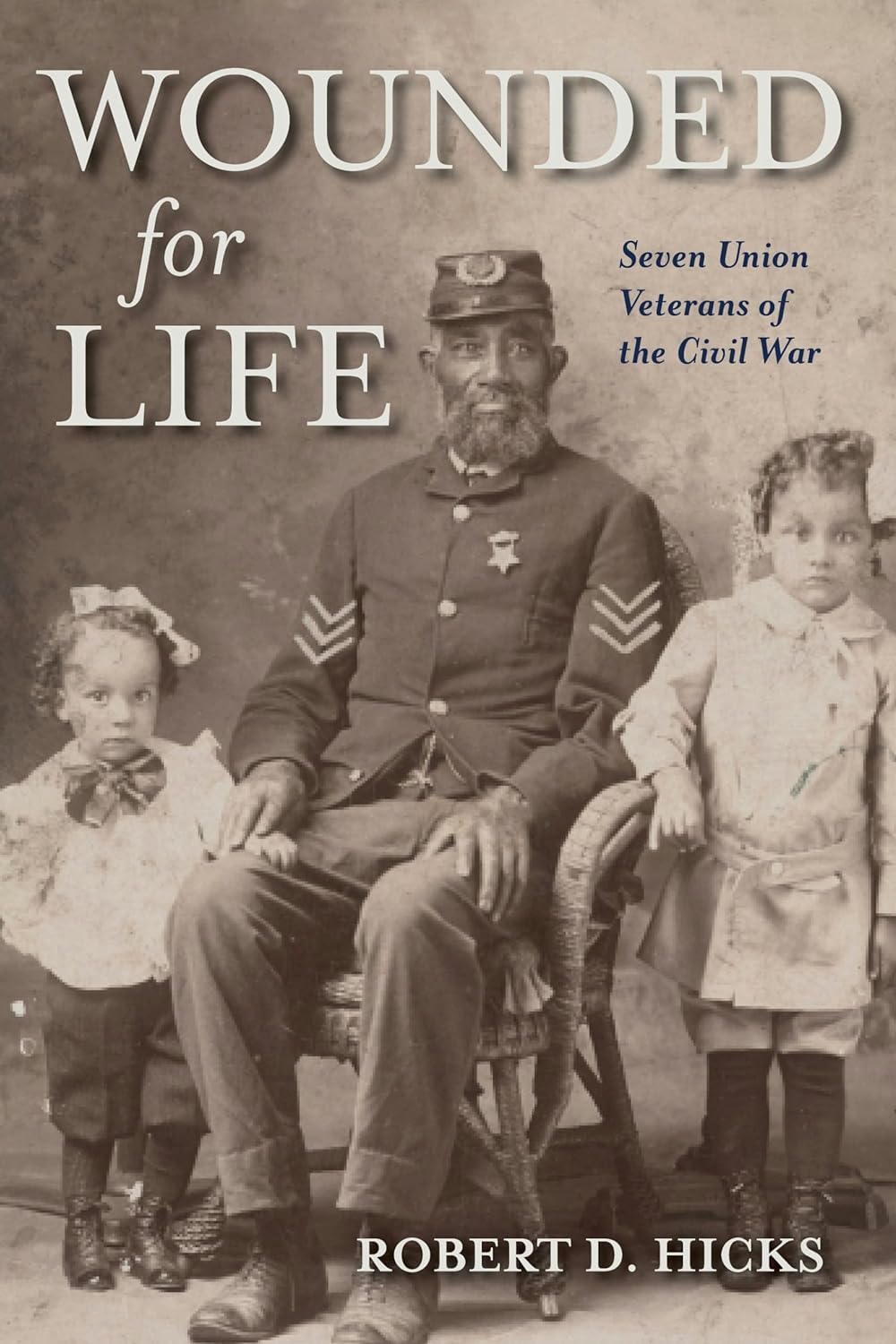

Wounded for Life: Seven Union Veterans of the Civil War. By Robert D. Hicks. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2024. Hardcover, 516 pp. $35.00.

Reviewed by Tim Talbott

The various challenges encountered by Civil War veterans after returning home from their campaigns have turned into a relatively new fertile field of study. Developing from some of the recent veteran’s studies is a sub-genre focusing specifically on veteran disability. Works like Brian Craig Miller’s Empty Sleeves: Amputation in the Civil War South; Sarah Handley Cousins’s Bodies in Blue: Disability in the Civil War North; The Left-Armed Corps: Writings by Amputee Civil War Veterans, edited by Allison M. Johnson, as well as her The Scars We Carve: Bodies and Wounds in Civil War Print Culture; and Sarah E. Chinn’s Disability, The Body, and Radical Intellectuals in the Literature of the Civil War and Reconstruction, among others, are informing students of the conflict about this previously overlooked but important topic. Joining this growing body of scholarship is Wounded for Life: Seven Union Veterans of the Civil War by Robert D. Hicks.

Hicks credits three previous studies as influencing his book: Brian Matthew Jordan’s Marching Home: Union Veterans and the Unending Civil War; Lindsay Tuggle’s The Afterlives of Specimens: Science and Mourning in Whitman’s America, and the above mentioned Bodies in Blue by Handley-Cousins. Organized into ten chapters that examine the lives of a Civil War surgeon, a sailor, and five soldiers (two of whom served in United States Colored Troops regiments), as well as an introductory and a concluding chapter, and another about the surgeon’s work with early electric therapy, the book also has two appendices.

In the introductory chapter, “Listening to Another’s Wound,” Hicks states, “my focus is on the veteran’s body as shaped by the trauma of the battlefield, the construction of a post-war identity in relation to that trauma, and the changing social circumstances of the last quarter of the nineteenth century as they impacted a traumatized body.” (5) To do so Hicks presents the case studies of the surgeon, sailor, and soldiers mentioned above.

Three of the profiled individuals were Medal of Honor recipients. Four of the men (all white) had ties to the surgeon, Silas Weir Mitchell, that Hicks includes. The servicemen all suffered from their wounds throughout the remainder of their lives. As Hicks ably tells it, “An amputation left a stump, but although a scar appeared to seal the wound, a moment never arrived when veterans deemed healing to be complete. Nerves continued to alter sensation or evoke pain, tumors appeared, unremoved bullets or bone fragments continued to torment. There was no finality or completion to healing.” (6)

Whereas others, such as Dillon Carroll with his fine study, Invisible Wounds: Mental Illness and Civil War Soldiers, cover psychological wounds, Hicks focuses primarily on physiological combat damage and service injuries, but he also shares some thoughts about the emotional toll exacted on wounded men.

As far as the featured profiles, readers first learn about Surgeon Silas Weir Mitchell (1829-1914), who served as a contract surgeon in Philadelphia during the Civil War and developed a particular interest in nerve damage. Capt. Henry Adolph Kircher (1841-1908), 12th Missouri Infantry, sustained three serious wounds at Ringgold Gap, Georgia, in late 1863, that required the amputation of his right arm and left leg. Coal Heaver Richard Downey Dunphy (1841?-1904) served aboard the famous USS Hartford. During the fight at Mobile Bay, Dunphy, hit by an exploding Confederate shell, endured the amputation of both arms at the humerus.

Pvt. Prestley Dorsey (1842?-1907), who is sometimes referred to as Prestley Dawson in his records, and who served in the 43rd United States Colored Infantry (USCI) is one of the two Black men profiled. After surviving the Battle of the Crater, Dorsey injured his leg while building earthworks at Petersburg. Soon after, he contracted malaria which required hospitalization. Despite these maladies, he continued to serve until mustered out in the fall of 1865. The other Black soldier, Sgt. Maj. Thomas Hawkins (1840-1870), 6th USCI, received three wounds at the Battle of New Market Heights while helping save his regiment’s colors for which he eventually received the Medal of Honor just before his death in 1870.

Capt. John Shields (1839-1923), 53rd Pennsylvania Infantry, was wounded through the neck in the Wheatfield fight at Gettysburg. Although Shields lived 60 years past his wounding and enjoyed a measure of personal success after the war, his wound reminded him daily of the limits it placed on his life. Like Capt. Shields, Lt. Col. Henry Shippen Huidekoper (1839-1918), 150th Pennsylvania, was wounded at Gettysburg, where he was shot in the right arm. After receiving some cursory field aid, he returned to the fight. Eventually making his way to a hospital in town doctors removed Huidekoper’s arm.

These soldiers’ wounds were only the beginning of their life-long challenges. Hicks’s research into their post-war lives, using pension records, newspaper accounts, personal correspondence, and other records is impressive, as is his writing in telling their struggles with their disabilities. Dr. Mitchell’s story, although markedly different than those of the wounded, is nevertheless interesting, too.

Hicks’s Wounded for Life gives readers yet another valuable contribution to the field’s impressive and growing body of Civil War veteran medical and disability scholarship. It should also help remind us that when it comes to our service people, our wars cast long shadows far beyond the years of the conflicts they fight in.

The human physical and emotional toll on the soldiers who survived is unfortunately discounted when Reconstruction is discussed. Rage and exhaustion are sometimes companions, leading to either murderous actions or avoidance of commitment.