Grant and Whiskey at Shiloh

In doing any research, a piece of evidence cannot usually be taken at face value. Timothy B. Smith once said in a talk on Shiloh in 2019 at Confederate Memorial Hall that when an official report said a unit fell back for ammunition, it usually meant they were driven from the field and didn’t want to admit it. Yet, that is clearly not always the case. Sometimes they were driven off because they ran out of ammunition, a too common problem for the Army of West Tennessee on Shiloh’s first terrible day. One way to check is to read reports made by nearby regiments, both friendly and hostile, as well as newspaper accounts, letters, memoirs and reminiscences. In a battle like Shiloh, fought by mostly green troops in broken terrain with organization quickly falling apart, it can be a daunting task.

After Shiloh, William C. Carroll got a misleading account of Shiloh out first. It said nothing of the camp being surprised, and Carroll depicted the April 7 attack at Review Field as decisive because Ulysses S. Grant led the charge. It created a more favorable view of the battle at first, one that reached Abraham Lincoln first. Then letters and other reports rolled in. Whitelaw Reid, while wrong about the extent of the surprise, provided a more detailed and accurate account overall, particularly of the fighting on April 7. Reid and Carroll created two Shiloh myths. Reid popularized the image of men being bayoneted in their tents and Benjamin Prentiss’s division being captured outright, which haunted Prentiss the rest of his life. Carroll’s account led to a slew of inaccurate images depicting the Review Field attack, many with Grant far ahead of his men, like he was Cardigan at Balaclava.

Grant’s career may have ended after Shiloh. His men despised him; soldiers in letters expressed their desire to watch Grant hang, one even saying he would volunteer to tie the rope. Newspapers called for his head. The Committee on the Conduct of the War considered an investigation and did eventually question Lew Wallace.

Grant survived Shiloh for several reasons. First, he did ultimately win the battle, although most soldiers gave Don Carlos Buell more credit after April 7. Second, Henry Halleck thought well of Grant as a fighter, and his only viable alternative was Charles Smith, who died weeks after Shiloh. Halleck did keep Grant at some distance, and his favorite officer after Shiloh was John Pope. Still, while Halleck berated Grant in private, in public he shielded him from censure, even if not loudly praising him. Third, Grant had the support of Elihu Washburne, who had Lincoln’s ear. Lincoln, for his part, while not writing in support of Grant, decided to retain him largely on Washburne’s advice and the fact that Grant had so far won two out of three battles, a record no one else could match.

After Shiloh rumors that Grant was drunk were published in the newspapers. However, in my research I have found no evidence of drinking. After the war Annie Cherry, whose home Grant used as his headquarters, praised him in the February 1893 edition of Confederate Veteran. She made it clear there was no drinking.

After Shiloh rumors that Grant was drunk were published in the newspapers. However, in my research I have found no evidence of drinking. After the war Annie Cherry, whose home Grant used as his headquarters, praised him in the February 1893 edition of Confederate Veteran. She made it clear there was no drinking.

Then I found an account that clearly said Grant drank whiskey at Shiloh.

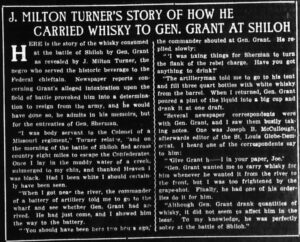

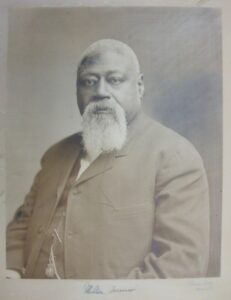

The July 9, 1911 issue of the St. Louis Dispatch carried a biography of James Milton Turner. Born a slave, his father purchased their freedom. During the war he was a servant to Madison Miller, who led a brigade at Shiloh. Turner left this account:

Is it true?

The evidence against it is strong. No one else saw Grant drink at Shiloh, and given the venom towards him after the battle the soldiers likely would have said something. I have run into quite a few men fantasizing about Grant’s execution, but nothing on him being drunk. Second, Grant did not drink during battles or active campaigns. Drinking for Grant was a function of boredom, loneliness, or social gatherings. Active military campaigns distracted him save for two quiet spots in the Vicksburg and Petersburg campaigns, where Grant did imbibe, but at neither point to the detriment of operations. The Vicksburg spree was recounted by Sylvanus Cadwallader. The Petersburg one is more murky, occurring shortly after the defeat at Jerusalem Plank Road. It does appear to have alarmed John Rawlins. A few officers, such as William F. Smith, believed Benjamin Butler found out about it and held it over Grant to keep himself in command. Of that nothing can be confirmed; the episode calls for more research, though.

Turner’s tale was told in 1911. The further back a memory is recalled, the more we recreate that memory over and over. Some, such as TIK (username of a World War II YouTube historian), have all but said memoirs are nearly useless. I disagree, but I will say they must be treated with the greatest care. Believing everything John Gordon and John Schofield wrote will not serve a Civil War historian very well, but each man’s account must be read. For the planning of Fort Stedman, Gordon is practically our only source. Schofield’s memor is vital for understanding how he got out of Spring Hill.

Yet, I would not wholly ignore Turner. First, Turner had no axe to grind. He was a man of good standing. After the war he was assistant superintendent of schools in Missouri, founded what became Lincoln University, and supported Grant, becoming consul general to Liberia in 1871. Turner was well regarded by Miller and aided him after Shiloh, where he was captured.

Turner was not among those who had a vendetta against Grant, such William S. Rosecrans. Nor was he a Confederate looking to get a cheap shot. It must be said, that does not discount the opinion of Rosecrans and others, only that those opinions must be considered in light of their relationship to Grant as surely as it must be with Carroll and Rawlins. In 1863 Rawlins wrote a report of Shiloh that was uncharitable to Buell and Wallace and does not accord well when compared to more contemporary accounts.

Turner tellingly says he saw Grant take some whiskey, but it did not impair him. It is possible Grant took a swig not knowing what it was and stopped, knowing he had to keep a clear mind. Of the many accounts there are of the fighting at Dill Branch, none mention a drunk Grant, even the men of the Army of the Ohio, who left many vivid accounts of chaos at Pittsburg Landing and marched by Grant before engaging James Chalmers’s brigade. Buell, who feuded with Grant after Shiloh, said nothing of Grant being drunk.

So while I doubt Grant took a drink, it seems to me if he did it was an accident and had no effect on him. Unfriendly reporters might have seen that which led to rumors being published. The men meanwhile, many with an understandable axe to grind, said nothing of it. Nor did Annie Cherry, who in the pages of Confederate Veteran had an audience willing to hear such a tale. Lastly, there is no account of Grant being drunk in a battle. Accounts such as Turner’s cannot be dismissed, regardless of how one feels about Grant. However, they must be weighed against what evidence we have.

Whether Grant was drunk at Shiloh cannot be proven either way, though it was proven in other instances. What can be proven is that he was away from his troops, at a significant distance, because he wanted to lodge in a comfortable house whilst recovering from leg injuries when his horse fell a few days earlier – and this is inexcusable. A general must never be away from his command while in enemy territory, and if he is too ill or injured to be with his men, he must officially turn over his command to a subordinate or replacement officer. That he failed to do so should have gotten him cashiered from the army, especially as he gave so much power to Sherman, whose incompetence was vividly on display that week. Then, following the battle, both lied in their after action reports, which should have gotten them sent to prison. Only the faultiness of mid-19th century communications systems kept both from being dismissed.

“Only the faultiness of mid-19th century communications systems kept both from being dismissed.” – Much more important were their political connections. Sherman had his brother and the Ewing family (two of which became generals in their own right) and Grant had Washburne and Yates. Sherman also had Halleck, who for his part censured Grant privately but not publicily. Lastly, Smith was dying. I think if Smith were healthy Grant would have been tossed out by Halleck.

This was a nice find. I wonder if there were any letters to the editor published in that or other St. Louis newspapers in response to it. It sounds like an event burned into his memory. BUT I find this hard to swallow: “General Grant poured a pint of whiskey into a big cup and he drank it in one draft.”

To me this is an example of what Shakespeare meant with the word “advantages” when he wrote in Henry V, “Old men forget, yet all shall be forgot, but he’ll remember, with advantages, what feats he did that day.”

That is a great Shakespeare line!

The part that makes this curious is that Turner was not making a “Grant was a drunk fool” comment. Perhaps it was not whiskey or it was watered down? Also, accounts where Grant did get drunk it appeared to not take much, making the tale again doubtful.

Great find and post.

Regarding your comment about claims of lack of ammunition, Kevin Getchell

in his Scapegoat of Shiloh: The Distortion of Lew Wallace’s Record by U.S. Grant, focuses on Grant’s odd decision to use his chief ordinance officer as a messenger to Wallace, causing that ordinance officer’s absence during a key period of time when he should have been handling ammunition distribution.

As I recall, Getchell also discusses the alleged Grant drinking incident.

I will look at my copy of Getchell for the drinking. As to ammunition I have heard that idea put forth and it might have traction. Should be noted Grant’s staff at Shiloh was not good, and only really improved after Vicksburg.

To me, the killer in the allegation is that journalists were present and saw this happen; given the storm that broke over Grant after the battle, I find it hard to believe that none of these journalists would have run with the story. As to why the old gentleman would have published this tale so long after the fact, I have no clue.