Book Review: From Dakota to Dixie: George Buswell’s Civil War

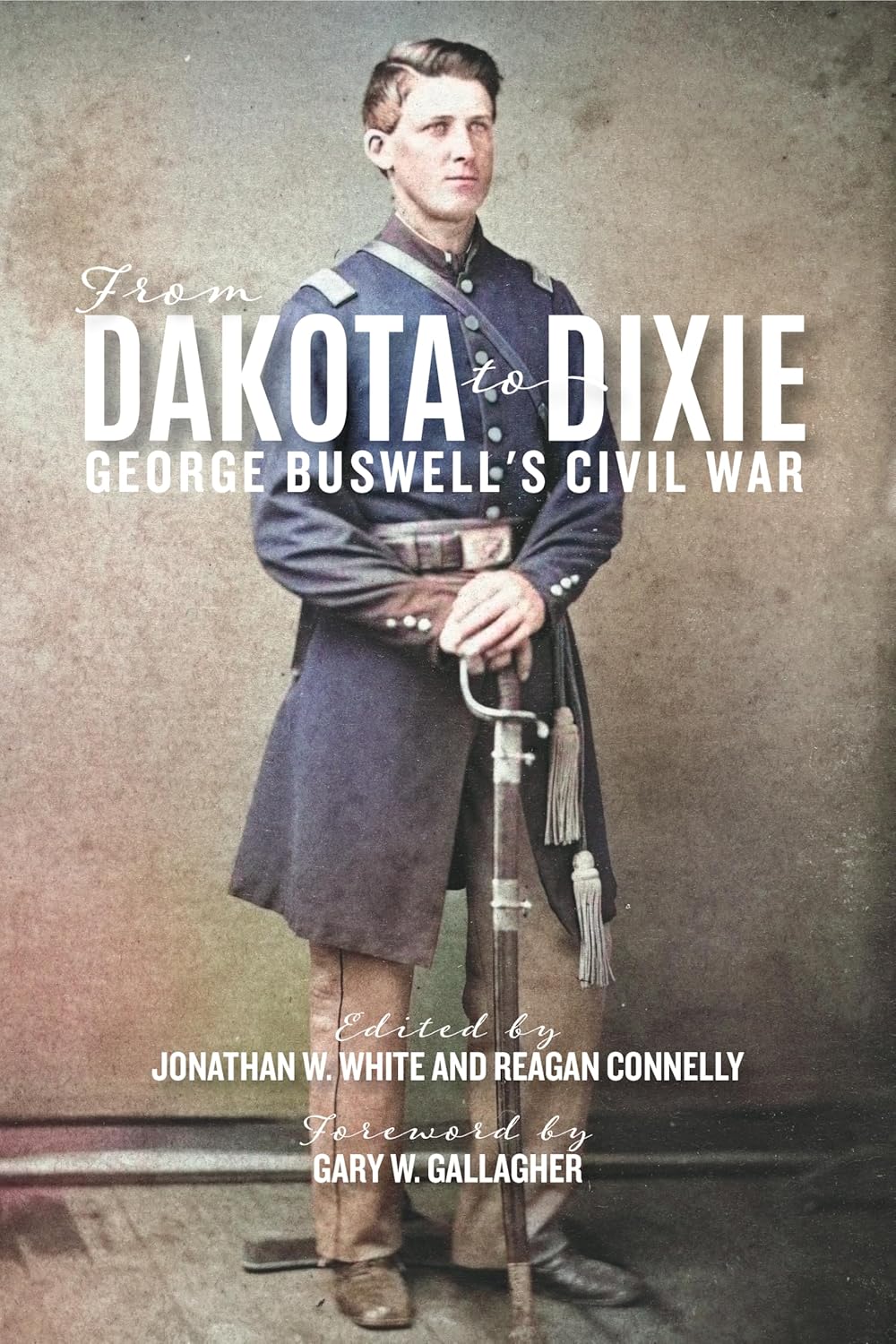

From Dakota to Dixie: George Buswell’s Civil War. Edited by Jonathan W. White and Reagan Connelly. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2025. Softcover, 288 pp. $35.00.

From Dakota to Dixie: George Buswell’s Civil War. Edited by Jonathan W. White and Reagan Connelly. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2025. Softcover, 288 pp. $35.00.

Reviewed by Patrick Kelly-Fischer

Two of the less discussed parts of American history from 1861-1865 are the Dakota War and the experience of soldiers serving in USCT regiments. From Dakota to Dixie: George Buswell’s Civil War, edited by Jonathan W. White and Reagan Connelly, is the latest attempt by historians to fill those gaps.

The book is primarily the diary of George Buswell, who volunteered for the 7th Minnesota Infantry, and later served as an officer in the 68th United States Colored Infantry. The diary begins with Buswell’s enlistment in the summer of 1862, and continues to December 31, 1864.

From Dakota to Dixie is split into two parts: The first 40% covers Buswell’s time in and around the Dakota War, while the remainder accounts for his time fighting the Confederacy, including in the Tupelo Campaign against Nathan Bedford Forrest. Both of those parts contain three to five chapters, each of which opens with a short introduction from White and Connelly. These chapter introductions provide important framing and context. Just like any rank-and-file participant in a major war, Buswell naturally lacked the perspective to know how his day-to-day, firsthand experiences fit into the bigger picture. White and Connelly’s chapter introductions quickly and succinctly fill the reader in; this is especially important given that Buswell participated in campaigns that are less well-known to most students of the Civil War.

There are countless diaries of Civil War soldiers—the relatively high level of literacy, and surviving written record is one of the remarkable things about studying this conflict. Each new diary we find, and that scholars take the time to transcribe, edit and publish, adds to our understanding of the war. But what stands out about Buswell’s diary?

The first is the insight it gives us into Midwestern Union soldiers who, at least in Buswell’s case, signed up to fight the Confederacy and were instead deployed against Native Americans. The first year of Buswell’s military career is spent engaged in the Dakota War of 1862, and dealing with its aftermath into 1863. In terms of both the size of the conflict and the attention it has received from historians, the Dakota War pales in comparison to virtually any Civil War campaign, but it still involved thousands of Union troops and ended in the largest mass execution in United States history.

Like many soldiers deployed outside of the major theaters of the war, Buswell experienced some frustration and resentment over his time in the Dakota War. Over the course of 1863, his diary shows that he’s increasingly chafing at the discipline and formality of garrison duty. On November 14, 1863, Buswell writes, “Common soldiers have no business to know, no rights except to obey orders.” (114)

In late 1863, Buswell and the 7th Minnesota are ordered south. Seeking an easier path to advancement, Buswell undertakes to become an officer in one of the newly formed regiments of United States Colored Troops. He provides detailed insight into the process of officer examinations and is ultimately assigned to the 68th United States Colored Infantry – the same unit as Daniel Densmore, another Minnesotan who experienced a similar trajectory to Buswell. It is interesting to see this work in conversation with the collection of Densmore family letters published just last year.

The bulk of Buswell’s combat experience comes with the 68th USCTs, including active participation in the Tupelo Campaign, which he records in excellent detail. Buswell was also something of an avid sightseer. He took good advantage of his wide-ranging assignments to visit, and record descriptions of, everything from the city of Nashville to a newly constructed ironclad in St. Louis. Buswell provides the kind of detail that helps expand our understanding of the world soldiers were living in.

Like many soldiers, Buswell’s views of politics, slavery, and the war itself were shaped by his service. He goes through a fascinating evolution on Union war aims, his views of Lincoln, and how he thought about abolition.

Buswell was a remarkably diligent diarist. By this reviewer’s count, he missed only 5 days without recording an entry. However, the diary ends abruptly at the end of 1864, missing Buswell’s service in 1865 and 1866, including the fighting at Fort Blakeley outside of Mobile.

This work is meticulously footnoted for both contemporary references that might not be clear to a modern reader, and to note anywhere that the transcription is in question due to handwriting and legibility. Along with the previously noted introductions to each chapter, and solid maps that provide geographic context, White and Connelly have done an excellent job of making Buswell’s diary an engaging and useful resource, that’s well worth the reader’s time.