Book Review: The Tenacious Nurse Nichols: An Unsung African American Civil War Hero

The Tenacious Nurse Nichols: An Unsung African American Civil War Hero. By Eileen Yanoviak. Essex: Lyons Press, 2025. Hardcover, 184 pp. $29.95.

The Tenacious Nurse Nichols: An Unsung African American Civil War Hero. By Eileen Yanoviak. Essex: Lyons Press, 2025. Hardcover, 184 pp. $29.95.

Reviewed by Sarah Kay Bierle

Lucy Higgs Nichols defied the odds and forged a new life for herself out of the crucible of the American Civil War. She escaped from slavery, served as a nurse with the 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment, trailblazed a new life in a northern community, and eventually received a military nurse’s pension. In a newly-released biography, author Eileen Yanoviak brings Nichol’s story to life through strong research and historical context.

Born enslaved in 1838, Nichols lived in North Carolina, Mississippi, and Tennessee, transferred to different members of the Higgs family in their wills. She gave birth to a daughter in 1860 and likely had a relationship with Calvin, an enslaved man. In 1862, the couple fled to Union army lines, taking Nichols’s daughter and seeking freedom as “contrabands of war.”

The nearest regiment was the 23rd Indiana, and in her self-emancipation journey, Lucy Nichols tied her future to this Union unit and to the history of these white men from the southern-central region of the state. Calvin eventually joined a USCT regiment, and the pair did not reunite after the war’s end. With the 23rd Indiana, Nichols first had employment as a laundress and cook.

In 1862, the regiment’s surgeon, Dr. Brucker, unofficially appointed Lucy Nichols to the position of regimental nurse. For the next three years, she cared for the sick and wounded soldiers. Long remembered for her compassion, steadiness, foraging skills, and cooking, Lucy Nichols was present at approximately 30 battle sites with “her regiment.” From Vicksburg and the March to the Sea, the Carolina Campaign, and the Grand Review in Washington DC, Lucy Nichols fought for freedom in her own way.

As the regiment mustered out of service in 1865, Nichols was on her own, but former regimental officers offered her employment in their family homes. She eventually settled in New Albany, Indiana and in 1870 married John H. Nichols, a veteran of the 8th U.S. Colored Heavy Artillery.

She was an honorary member of the Sanderson Post of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) in New Albany, regularly attending meetings, laying flowers during Memorial Days, and marching in local parades. Her presence, with white veterans in solidarity beside her, challenged local social norms and visibly reminded the community of the different stories and types of service during the war. Just as Lucy Nichols had supported them during their hospital experiences, the regiment’s veterans stood by her in the 1890s as she petitioned for years for an Army Nurses Pension. Eventually, by a special act of Congress, Nichols’s wartime work as a nurse was officially recognized, and President William McKinley signed the bill, granting her $12 per month. Versions of her story appeared in newspapers across the nation. She remained a respected member of New Albany communities until her death in 1915.

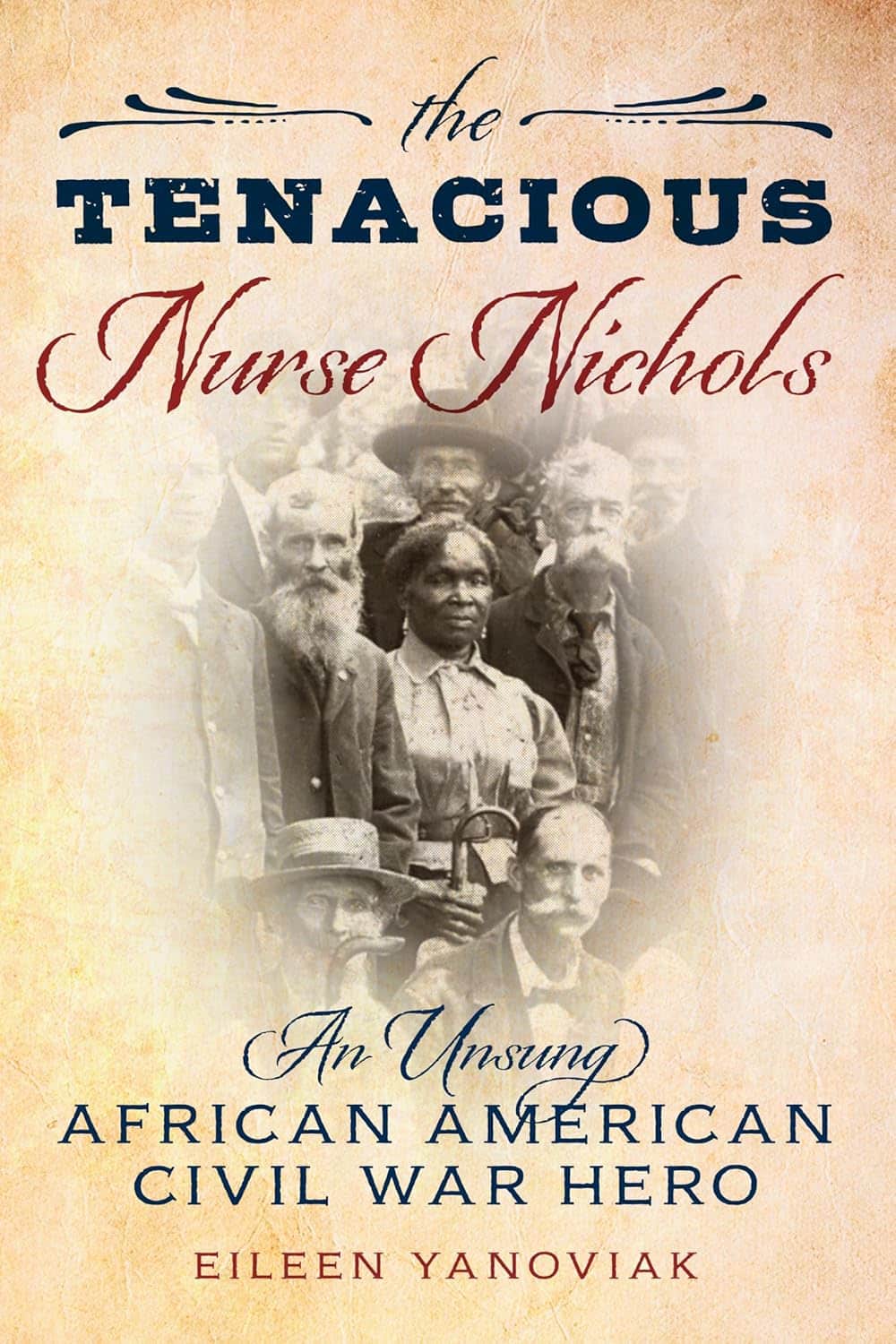

Throughout the biography, Yanoviak draws on primary sources from Lucy Nichols’s life to weave comprehensive details about her experiences. Where Nichols’s story falls silent in the records, the author skillfully points to other primary sources about enslavement, freedom seeking, nurses’ service, and civil rights to bring fresh considerations and context. Biographical details are well-supported with general historical context, making this book readily readable for a general audience or a well-versed Civil War researcher. The chapter outlining the political struggle for nurses’ pensions outlines the details exceptionally well. Reflections on the preserved photographs of Nichols are also particularly insightful on women’s place and image with Civil War veterans in the post-war years.

The author respectfully acknowledges the challenges of writing this biography, noting in the introduction: “While I can relate to some of Lucy’s very human struggles as a woman and mother…I cannot truly understand what tragedies and barriers she had to overcome because of her race and history.” (x) The book concludes with an epilogue, praising the work of community and local historians to preserve Lucy Nichols’s story over the years and reflecting on new pieces of art and monumentation that have recently been created in her memory.

With its well-crafted text and contextualized history, The Tenacious Nurse Nichols will easily appeal to academics, public historians, and history readers who are interested in Black history, women’s history, Indiana history, Civil War medical history or are looking for a lesser-known biography. This is a historical account that should rank alongside some of the well-known narratives of Susie King Taylor and Harriet Jacobs; it adds another biographical look at the experiences of enslaved women who found freedom and futures through self-emancipation and war work. “In contrast to perceptions that enslaved people were passive recipients of freedom bestowed on them by Yankees, Lucy’s story…illustrates the intense self-sacrifice made by Black men and women to attain freedom. They, too, went deep into war zones, working to survive bloody battles in a brutal Civil war that tore the nation apart…. Lucy’s struggle can be linked to the central narrative of agency and natural rights for Black Americans who worked to define, shape, and control their own lives….” (63)

A fine review of an interesting story, and the illustration used for the book’s cover is compelling.

Excellent, Sarah