Book Review: Waging War for Freedom with the 54th Massachusetts: The Civil War Memoir of John W. M. Appleton

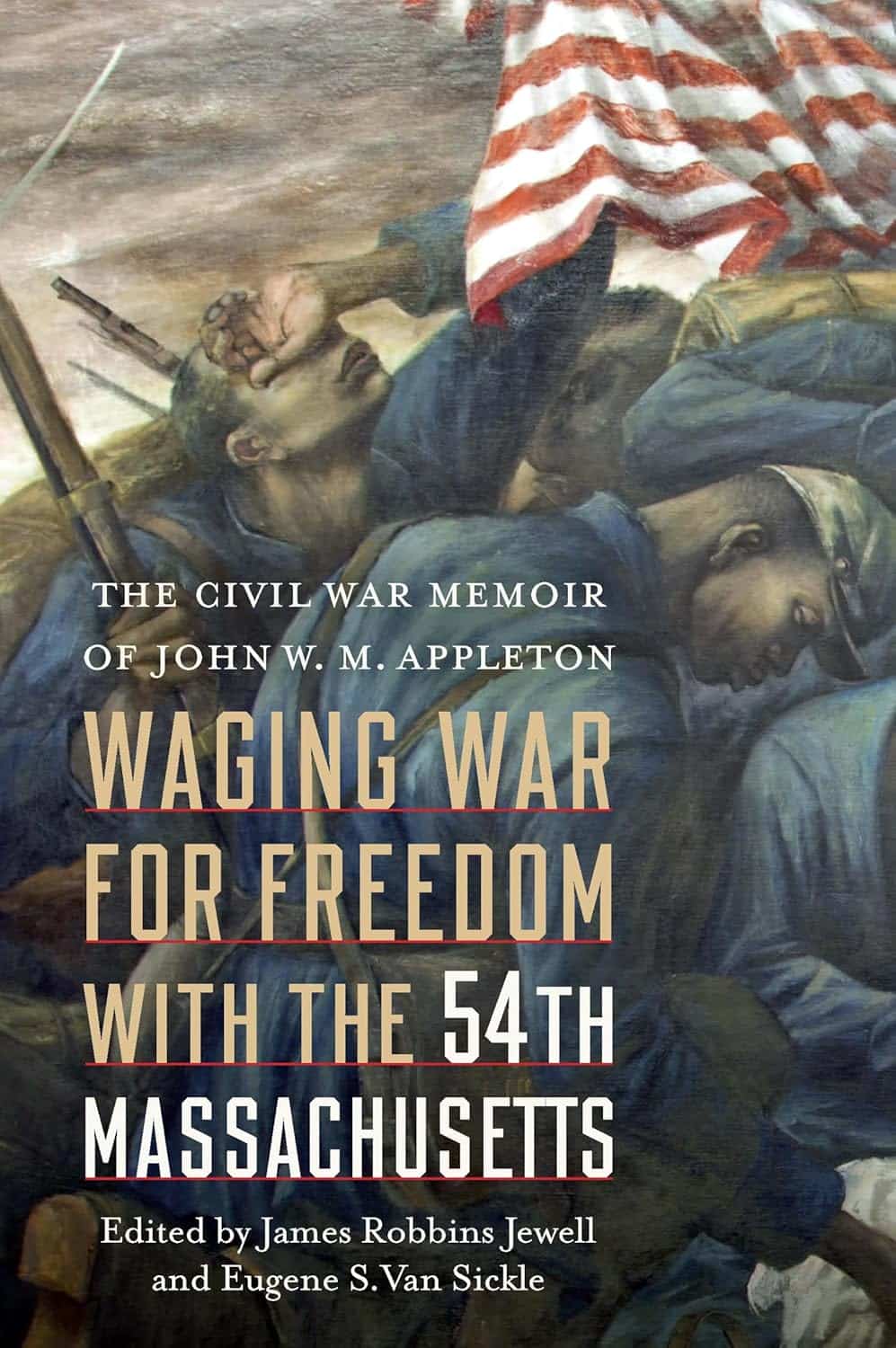

Waging War for Freedom with the 54th Massachusetts: The Civil War Memoir of John W. M. Appleton. Edited by James Robbins Jewell and Eugene S. Van Sickle. Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2025. Hardcover, 368 pp., $39.95.

Waging War for Freedom with the 54th Massachusetts: The Civil War Memoir of John W. M. Appleton. Edited by James Robbins Jewell and Eugene S. Van Sickle. Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2025. Hardcover, 368 pp., $39.95.

Reviewed by Tim Talbott

The 54th Massachusetts Infantry is the most widely recognized Black regiment that the Civil War produced. There are several reasons for this. A large part of their renown comes from both being an early African American regiment raised in a Union state and their relatively quick participation and good performance in combat in July 1863 at James Island followed by their assault at Battery Wagner, South Carolina. The death of their colonel, Robert Gould Shaw, at Wagner also added to their legacy. However, it is the 1989 Academy Award-winning film Glory that has cemented the 54th’s place in the modern public’s mind.

As one might imagine, the 54th has generated a significant amount of published material. Studies about the regiment, their colonel, their most famous fight, as well as published primary sources and memoirs from their enlisted men and officers are available and continue to appear.[1]

Adding to the 54th memoir category is Waging War for Freedom with the 54th Massachusetts: The Civil War Memoir of John W. M. Appleton, edited by James Robbins Jewell and Eugene S. Van Sickle. This book though is a bit different from many memoirs. Its contents appear as journal entries that Capt. Appleton created in the 1880s based upon the clear information that he wrote in letters to his wife during the war. As editors, Jewell and Van Sickle note, “As a descriptive observer of places and people, Appleton humanizes the men in the ranks, especially his fellow officers, in a way that a regimental history does not.” (xiv) This is a book where the “real war” gets put in. More on that in a bit.

Jewell and Van Sickle provide a helpful introduction that not only allows readers to get a better idea of Appleton the person, but they also provide important background information on the formation of the 54th for those who may not be familiar with its origins. Born in 1832, Appleton came from a family with deep Boston roots. His father, a physician, appeared to be a model for young Appleton as he enrolled in Harvard’s medical school. Apparently though he did not find the study of medicine to his liking and dropped out after a year and began working as a clerk.

Appleton was over 30 years old and married when he received his appointment as the 54th’s first commissioned officer. Unlike a number of other Harvard-educated Boston officers, Appleton was quite progressive in his thinking on race. Writing to Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who would serve as colonel of the 1st South Carolina Colored Infantry (later designated as the 33rd United States Colored Infantry), Appleton who initially sought a position with Higginson’s unit, penned: “the two great problems that demand our attention in connection with the freedom of the slave are firstly, will the freedmen work for his living & secondly will he fight for his liberty? I believe that he will do both and I desire to assist him to do the latter.” (8) Instead of serving with Higginson, Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew had other plans for Appleton, commissioning him as a second lieutenant in Company A of the 54th.

The editors divide the book into ten chapters that cover Appleton’s service with the famous unit. Nine of the chapters cover from his training efforts at Camp Meigs to his resignation in November 1864, a period that saw him rise from second lieutenant to major and suffer a wound at Battery Wagner and a debilitating sunstroke. Chapter Ten and an Epilogue round out the book providing information on the unit’s service until it mustered out and Appleton’s post war career and tragic death in 1913.

Appleton wrote his memoir for his children, not for publication. We are fortunate that it is now in print due to the detailed descriptions he provides. As mentioned above, he includes in his accounts the types of things that students who desire to know “the real war” want to read. Again, borrowing from his letters home, Appleton gives some gritty details of soldiering. He covers a plethora of subjects that gives us amazing insights. For example, in telling about a day in November 1863, and now located in the Union captured Battery Wagner, he writes about going to where he was wounded during the battle four months earlier and watching men digging fortifications: “The shovels kept turning up the usual litter of ground that has been fought over, rags, bullets, bits of iron, wood, and brass, and one spade threw up a cap which belonged to a U.S. soldier.” Close by he “found some tatters of a U.S. flag, and a part of the fringe from its edge.” (111) It had a bullet hole through it, and he sent it home as a keepsake.

The environment of the Department of the South receives lots of comments. Appleton battles all kinds of pests, from rats, mice, sand flea, and mosquitos to crabs and snakes. He bathes where there are alligators and sharks. Hot summer months and frigid winters on the coast constantly test his and his men’s commitment. Also included are challenges unique to serving with a Black regiments. There are fears of being captured and possibly executed. There is worry about his men not receiving equal pay and the impact his has on their morale and the concerns it creates for the welfare of their families back home. All receive vivid descriptions as only one who experienced it can explain it.

Wonderfully edited, Waging War for Freedom with the 54th Massachusetts is an excellent addition to the existing body of published primary sources and personal accounts by Black soldiers and their white officers. It captures soldier life in a Black regiment and tells it as honestly as any previous work available.

[1] Among others these include: A Brave Black Regiment: History of the Fifty-Fourth Regiment of the Massachusetts Infantry, 1863-1865 by Luis F. Emilio; Where Death and Glory Meet: Colonel Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Infantry by Russell Duncan; Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, edited by Russell Duncan; Thunder at the Gates: The Black Civil War Regiments that Redeemed America by Douglas R.. Egerton; A Voice of Thunder: The Civil War Letters of George E. Stephens, edited by Donald Yacovone; On the Alter of Freedom: A Black Soldier’s Civil War Letters from the Front-Corporal James Henry Gooding, edited by Virginia M. Adams; Hope & Glory: Essays on the Legacy of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, edited by Martin H. Blatt et al.; and the forthcoming Shaw biography by Kevin Levin.

Excellent work as always but you leave a question-how did Appleton die?

Ha! Can’t provide a spoiler alert!

Guess I have to read the book!