Breaking the Line at Fort Stedman: John B. Gordon’s Infiltration Innovation

ECW welcomes back guest author M.A. Kleen.

In the early morning hours of March 25, 1865, North Carolina pioneers from Brig. Gen. James A. Walker’s division, armed with hatchets and masquerading as deserters, cleared paths through the abatis and chevaux-de-frise in the no-man’s-land before Fort Stedman, just north of Petersburg.

Three 100-man assault groups followed with orders to seize Fort Stedman and nearby artillery batteries. The fort, less than an acre in size, was in a salient close to the Confederate works (613 feet away). Because of that proximity, repairs were difficult, and wet, low ground flooded its bombproofs.[1] It was named after Col. Griffin A. Stedman, who had died the previous August.

Three more groups of hand-picked Louisiana veterans from Lt. Col. Eugene Waggaman’s brigade moved next, with special orders to infiltrate deep into the enemy rear toward Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters at City Point, where, unbeknownst to them, President Abraham Lincoln was visiting.

Eleven thousand, five hundred men, with another 8,200 in support, approximately one-third of the Army of Northern Virginia, waited to exploit the gap. Had the attack succeeded, it would have knocked Grant’s army on its heels and potentially delayed the war’s end by several months.

Despite initial success, however, the infiltration groups became lost in the dawn gloom and the maze of Union trenches and were forced to fall back. Union Brig. Gen. John F. Hartranft, who later became governor of Pennsylvania, organized a counterattack that pushed the Confederates out and retook the fort, inflicting heavy casualties the rebels could ill afford.[2]

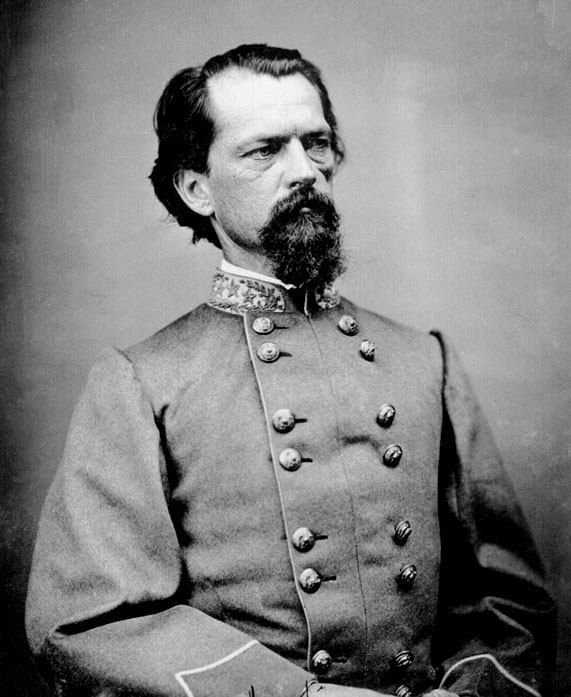

The meticulously planned attack on Fort Stedman was conceived by Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon, who was so convinced of its soundness that he attributed its failure to the hand of God.[3] Gordon innovated on similar tactics used successfully elsewhere on a smaller scale to develop something strikingly modern in its approach.

Some historians have described the American Civil War as the first modern war. While that may be overstated, it is hard not to miss the similarities between the trench lines around Petersburg and those of northern France in the First World War.

There, more than fifty years later, war planners faced the same problem. Barbed wire had replaced wooden obstacles, and machine guns and bolt-action rifles increased the range and deadliness of fire, but the challenge of breaking through a strong network of static defenses vexed Grant and Lee as much as it did Erich Ludendorff and Ferdinand Foch.

In 1915, French General Headquarters (GQG) issued a widely distributed (but largely ignored) pamphlet of tactical instruction abbreviated as Note 5779. It contained the kernel of what would become known as infiltration tactics, tested and elaborated by Capt. André Laffargue.[4]

Independently, German Capt. Willy Rohr’s experiments with combat engineer companies led to the creation of Stosstruppen, or “shock troops,” which the Imperial German Army used to great effect in breaking through Allied trenches during the spring 1918 Operation Michael. These infiltration tactics, in which small, specially trained units breached weak points ahead of the main assault, were remarkably similar to those employed by Gordon in his attack on Fort Stedman.[5]

Gordon’s plan involved several waves. The first, about one hundred men, cleared paths in the obstacles by moving forward under the pretense of surrender and then overwhelming Union picket posts. Confederate deserters were a common sight by early spring 1865, and Union pickets had little reason to suspect anything unusual.

As noted, three groups of one hundred men each followed with unloaded muskets, described by historian Noah Andre Trudeau as “storming parties,” to quickly and quietly seize the batteries around the fort, which they did.[6]

A third wave of special-mission groups moved beyond the fort to widen the breakthrough and, if possible, capture Grant’s headquarters and sow panic and chaos behind the lines. This was to be followed by a massive assault of nearly 20,000 men, which was called off after the advanced groups failed in their objective.

Gordon’s attack faltered primarily because of Hartranft’s quick thinking and vigorous defense, but also because Gordon’s men lacked the specialized training, discipline, and equipment to carry out so complex an operation. It took months, if not years, of training and practical experience for Rohr’s shock troops to reach their level of effectiveness by early 1918.

Gordon developed his plan over a “week of laborious examination and intense thought” and proposed it to Gen. Robert E. Lee on March 22, 1865. Lee approved it the following evening. Gordon therefore had exactly one day (the 24th) to prepare and explain the detailed, methodical plan to his subordinates and supporting commanders.[7]

The attack would have been difficult for well-fed, well-trained, and well-organized soldiers to execute, let alone the half-starved and demoralized men and officers under Gordon’s command. Nevertheless, the initial stages of the assault, in Gordon’s own words, “exceeded my most sanguine expectations.”

It was the Army of Northern Virginia’s last offensive, and as brilliantly as it began, it ended in disaster. The Confederates lost more than 4,000 men: about 600 killed, 2,400 wounded, and 1,000 missing or captured, to the Union’s 1,044 total casualties.

Just over one week later, the Union army broke through Lee’s Petersburg defenses and began the long pursuit to Appomattox Court House—and the end of the war.

Even so, Gordon’s plan for the attack on Fort Stedman remains a remarkable example of innovative tactical thinking, well ahead of its time. With proper preparation and coordination, it might have succeeded. The hard, bloody lessons of infiltration had to be relearned on the battlefields of the First World War before such tactics were again used.

M.A. Kleen is a program analyst and editor of spirit61.info, a digital encyclopedia of early Civil War Virginia. His article “‘A Kind of Dreamland’: Upshur County, WV at the Dawn of Civil War” was recently published in the Spring 2025 issue of Ohio Valley History.

Endnotes:

[1] William H. Hodgkins, The Battle of Fort Stedman (Petersburg, Virginia) March 25, 1865 (Boston: By the author, 1889), 10-11.

[2] John Horn, The Petersburg Campaign: June 1864-April 1865 (Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1993), 213-216.

[3] Noah Andre Trudeau, The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864-April 1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993), 354.

[4] Simon Jones, “Infiltration by Close Order: André Laffargue and the Attack of 9 May 1915,” Simon Jones Historian, March 5, 2014. https://simonjoneshistorian.com/2014/03/05/infiltration-by-close-order-andre-laffargue-and-the-attack-of-9-may-1915/

[5] See: Bruce I. Gudmundsson, Stormtroop Tactics: Innovation in the German Army, 1914–1918 (New York: Praeger, 1989).

[6] Trudeau, 335.

[7] John B. Gordon, Reminiscences of the Civil War (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1904), 403-405.

Excellent article. John Gordon an outstanding and innovative officer.

Thank you!

My great uncle, Felix Kauffman, was a member of the 200 Pennsylvania that recaptured Fort Stedman from Gordon’s Confederates He was wounded during the counter assault on the fort. He married my grandfather’s sister. I added the photo of the fort to his profile on my ancestry page, thank you. I had already added General Hartranft’s Battles & Leaders article to his profile.

Thank you for a great article. I liked the ties to future trench warfare, strategy, and learning more about the planning that went into it. I’m sure there was alot of information that, for brevity, didn’t make it in.

Appreciate it. If you check out that article by Simon Jones in my citations, it’s very comprehensive

Gordon had previous experiences of observing the techniques of breaking defensive fortifications. He led efforts to rebuff Union attacks to punch through the Confederate defensive works at Spotsylvania, and then recommended a successful offensive attack at Cedar Creek. As a keen observer of the successes and failures of those prior experiences, he made a successful effort to punch through the earthworks at Fort Stedman. But it was for naught as result of too few attempting to overwhelm too many at a point too late in the war.

Thanks for the description.

Dr. Lewis Wilder, “HistoryGone Wilder,” recently dropped a podcast on the Fort Stedman action of March 25,1865 as part of his many episodes on the Siege of Petersburg. His you tube video includes some maps to show the units’ locations and movements and the fighting at a nearby redoubt that was engulfed in the fighting back and forth.

Love his YouTube channel!

My g-grandfather, James Chapman of the 42nd Va Inf, attacked a little further down from Stedman and survived the sprint back to safety. I often think how lucky I am to be born considering he survived Culp’s Hill, May 3rd Chancellorsville, 3rd Winchester, Fisher’s Hill, Spotsylvania CH, Hatcher’s Run and many more, without a scratch.. His grandfather survived being a POW on a British ship ,Belevedere during the Revolutionary War

.