A Visit to the Margaret Mitchell House in Atlanta: How the Renovated Museum is Addressing the Controversies Surrounding “Gone With the Wind”

It has been called “the greatest love story ever told” and “the epic novel of our time.” It sold more than 1,000,000 copies in the first six months, more than 30 million to date, and has been translated into more than forty languages. Its author was awarded the Pulitzer Prize, and the movie won ten Academy Awards, including Best Picture. The American Film Institute ranked it the fourth greatest American movie of all time, and it remains the biggest theatrical release of all time, taking in more than $1.8 billion when adjusted for inflation.

It has also been called “racist” and “evil,” criticized for its “sugarcoated white supremacy,” and blamed for “weav[ing] a spell that has perverted our national vision of slavery and warped our understanding of the Civil War and its long, vicious aftermath.” [1] Its pages have been criticized for holding “the usual age-old slanders: that Negroes did not want their freedom and that it had to be forced upon them; that all except a few Uncle Tom Negroes were rapists and murderers; that Negro legislators of Reconstruction were corrupt and dishonest; that the Civil War was all a mistake; and that Negroes were inferiors, and little less than brutes.” [2]

Clearly, people have strong opinions about Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind, as well as Hollywood producer David Selznick’s movie version of the book. The book first appeared on book shelves on June 30, 1936; the movie, on screens on December 15, 1939 – and we’re still talking about both today (check out this June 2020 ECW GWTW series by Sarah Kay Bierle). Its impact over the decades on both popular thinking and culture has been enormous.

It is also the novel that first made me interested in history back when I read it in eighth grade. Despite its historical inaccuracies, which I now more readily recognize and acknowledge, Gone With the Wind brought the American history I was studying that year in school to life and piqued my interest in historical fiction. So, when I first visited Atlanta in February 2024, I was anxious to visit the Margaret Mitchell House to learn more about her life and work.

Unfortunately, the house was closed for renovations at the time and had been since March 2020. While Covid likely prompted that initial closure, I had to wonder if the ongoing “renovations” had to do with revising how the museum told the story of this controversial book. Spring and summer of 2020 had prompted many such discussions and changes, sparked by nationwide protests in response to the killings of Breonna Taylor (March 13) and George Floyd (May 25), as well as calls to reform or “defund” the police and remove Confederate monuments. Many cities heeded those calls.

As Sarah Kay Bierle explained in the first post of her series, “In case you missed it, Gone With The Wind hit the trending list because HBO Max pulled it from their list of movies. Shortly after, news arrived on the scene that it will be returned sometime in the future with some disclaimers and maybe some historical context. In the meantime, some advocates are voicing their opinion that it should never come back.”

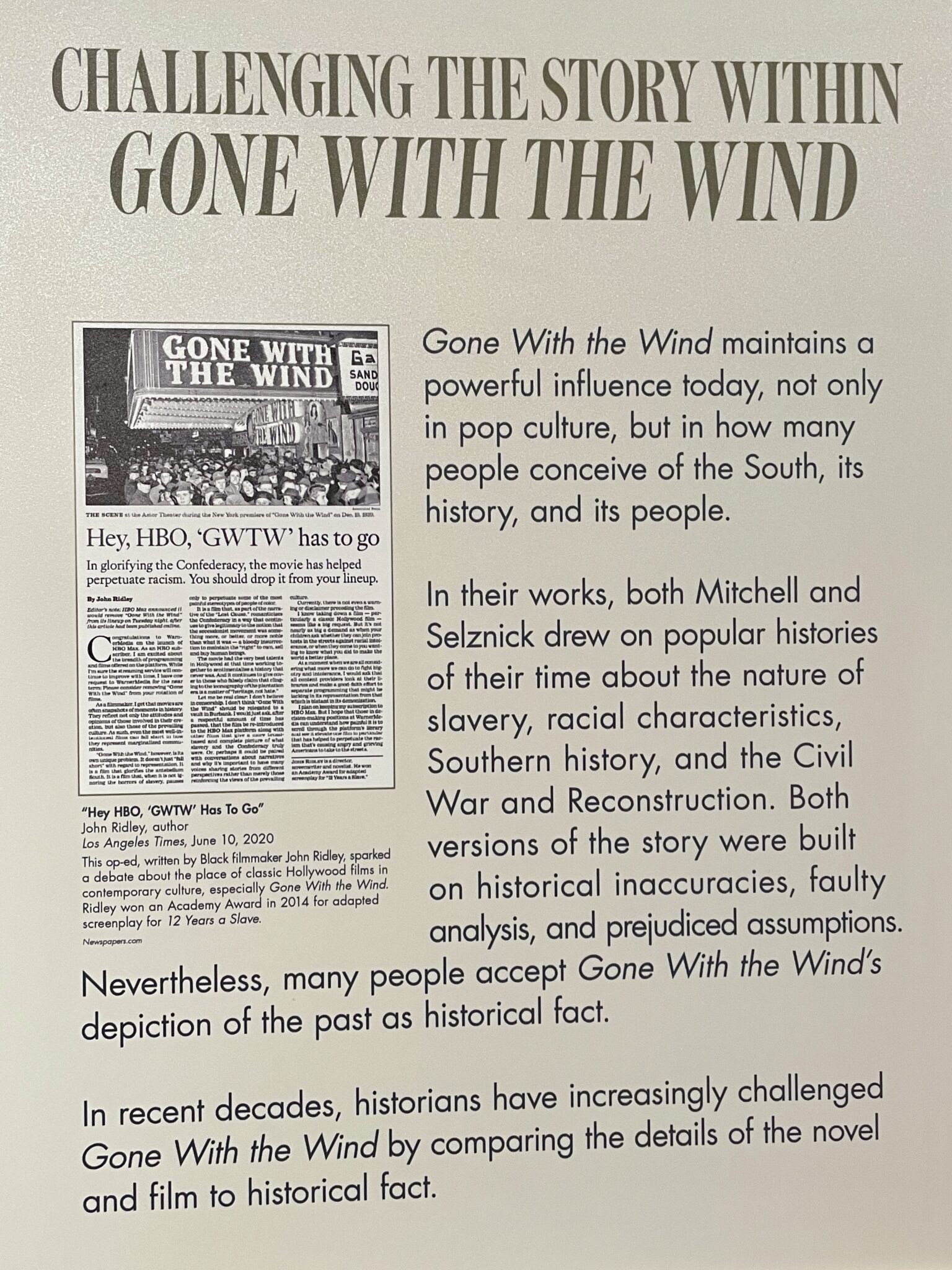

One voice calling for HBO to take the film off its roster – at least until “other films that give a more broad-based and complete picture of what slavery and the Confederacy truly were” could be added to the HBO Max platform – was Black director, screenwriter, and novelist John Ridley, who won an Academy Award for his adapted screenplay for 12 Years a Slave. In an opinion piece for the Los Angeles Times, he called Gone With the Wind “its own unique problem,” then went on to elaborate:

“It is a film that, as part of the narrative of the ‘Lost Cause,’ romanticizes the Confederacy in a way that continues to give legitimacy to the notion that the secessionist movement was something more, or better, or more noble than what it was—a bloody insurrection to maintain the ‘right’ to own, sell and buy human beings. The movie had the very best talents in Hollywood at that time working together to sentimentalize a history that never was. And it continues to give cover to those who falsely claim that clinging to the iconography of the plantation era is a matter of ‘heritage, not hate.’” [3]

HBO Max removed Gone With the Wind from its platform the day after the editorial’s publication. Two weeks later, the film returned accompanied by two videos discussing its historical context. The opening, highly romanticized text that Selznick had added, which does not appear in the book, remained: “There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South … Here in this pretty world Gallantry took its last bow … Here was the last ever to be seen of Knights and their Ladies Fair, of Master and of Slave … Look for it only in books, for it is no more than a dream remembered. A Civilization gone with the wind…”

So, how does the now renovated Margaret Mitchell House in Atlanta handle all of this?

One key way is to acknowledge many of these criticisms. Its current exhibit, titled Telling Stories: Gone With the Wind and American Memory, does just that.

Ridley’s editorial is included on one of the museum’s panels, acknowledging that both Mitchell and Selznick “drew on popular histories of their time about the nature of slavery, racial characteristics, Southern history, and the Civil War and Reconstruction. Both versions of the story were built on historical inaccuracies, faulty analysis, and prejudiced assumptions.” Several panels express the importance of “flipping the script” and focusing on alternative narratives, such as the TV miniseries Roots, movies Selma and 12 Years a Slave, and Alice Randall’s novel The Wind Done Gone, all of which feature strong, more complex Black characters and a more honest look at the history and legacy of slavery in the United States.

As another panel – one that also includes a slave sale notice – states: “Among the lasting legacies of Gone With the Wind is a nostalgic image of the Old South. It is a South that never existed—written for the film as a pretty world of cavaliers and Southern belles, grand plantations, benevolent masters, and happy slaves. In the antebellum South, the reality was very different…. The harsh reality of Old South slavery contradicts the benign, idealized depictions in Gone With the Wind. Slavery was unforgiving, cruel, and violent.”

The museum highlights the realities of slavery with facts about the history of slavery in Georgia and other states. Various panels detail the physical and sexual abuse enslaved people endured, tell the stories of many who sought their freedom or participated in various acts of resistance, and present excerpts from books such as Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglas and Harriet Jacobs’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl that give voice to those who endured this oppression.

One panel explicitly acknowledges slavery as the cause of the Civil War. Despite Ashley Wilkes’s professions in both the novel and film that he would have freed his family’s slaves when his father died if the war had not already freed them, implying that slavery was already on the wane, “That was hardly the case. The documents establishing the Confederate States of America along with the words of its leaders make clear that slavery was the primary reason for secession, and its protection was central to Confederate ideology.”

Another panel addresses the myth of the “War of Northern Aggression,” which one fiery movie montage that casts U.S. General William T. Sherman as “the Great Invader” clearly promotes with the text across the screen: “To Split the Confederacy, to leave it crippled and forever humbled, the Great Invader marched … leaving behind him a path of destruction sixty miles wide, from Atlanta to the sea.”

Many in the South argued that secession was a legal right, that they just wanted to maintain their “gentler” way of life, and that the war was a result of Northern invasion. In reality, as the panel points out, “Sherman’s scorched-earth ‘March to the Sea’ from Atlanta to Savannah was a fatal blow to the Confederacy. The film ascribes the march to Sherman’s ‘evil intent,’ thus demonizing U.S. soldiers. By contrasting alleged Union barbarism with Confederate nobility, Gone With the Wind reinforces the false belief that the war resulted from Northern aggression, rather than the existence of slavery.”

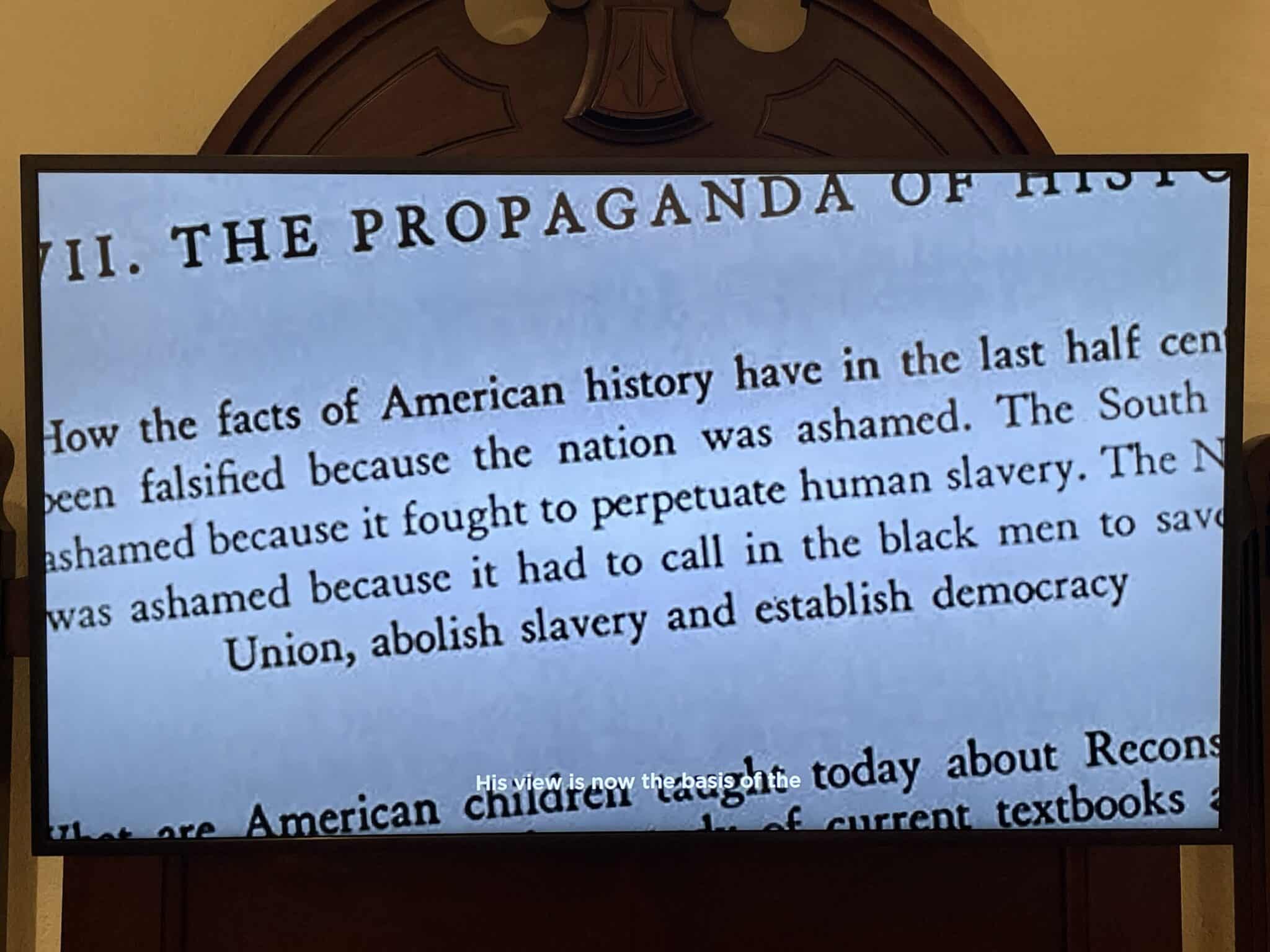

The museum also addresses inaccuracies related to Reconstruction, many of which were promoted by historians of the time, especially Columbia University’s Dunning School. Founder William A. Dunning saw Reconstruction as “an overbearing Federal government attempting to impose naïve ideals of racial equality on the South,” and “his views helped justify Jim Crow segregation and influenced popular views of Reconstruction across the country,” one panel explains.

Historian and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois sought to refute Dunning’s analysis in his 1935 book Black Reconstruction in America, but Dunning’s view remained the dominant view for most of the 20th century and had a big impact on Mitchell’s writing. The museum includes a letter from her correspondence with C. Mildred Thompson, a Dunning historian who wrote Reconstruction in Georgia, in which Mitchell called Thompson’s book her “mainstay and [her] comfort” and a “marvelously valuable work.”

A large section of the museum is designed like a mini-theater to share photos, facts, and stories from the movie’s glamorous, glitzy – and segregated – premiere. As one panel explains and various photos depict, “The three-day event featured a star-studded parade through the downtown streets, a lavish Junior League hoopskirt costume ball, a reception at the governor’s mansion, VIP tours of The Battle of Atlanta cyclorama, and, of course, the world premiere screening of Gone With the Wind.”

However, neither actress Hattie McDaniel, who became the first Black performer to receive an Academy Award for her depiction of Mammy, nor any of the other Black actors were able to attend the costume ball or the segregated premiere at Loew’s Grand Theatre. Neither did McDaniel’s picture appear in the Atlanta premiere’s 18-page, full-color program, though it did appear in most cities. When she walked up to receive her Oscar at the award ceremony held at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub in Los Angeles, she did so from a small table in the back, where she and her date sat apart from her white castmates.

Interestingly, the only Blacks allowed into the Junior League ball were members of the Ebenezer Baptist Church choir, who were dressed in slave attire and performed spirituals on the steps of a recreated plantation house. Among them was 10-year-old Martin Luther King Jr., whose father, then the senior pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church, was criticized for allowing his church to participate in the performance. Another Atlanta pastor, in a scathing editorial in the Atlanta Daily World, wrote, “The celebration of the past three days and the preparations made for it, tend to confirm what thousands have firmly believed, that at heart the South is still the Confederacy.” [4]

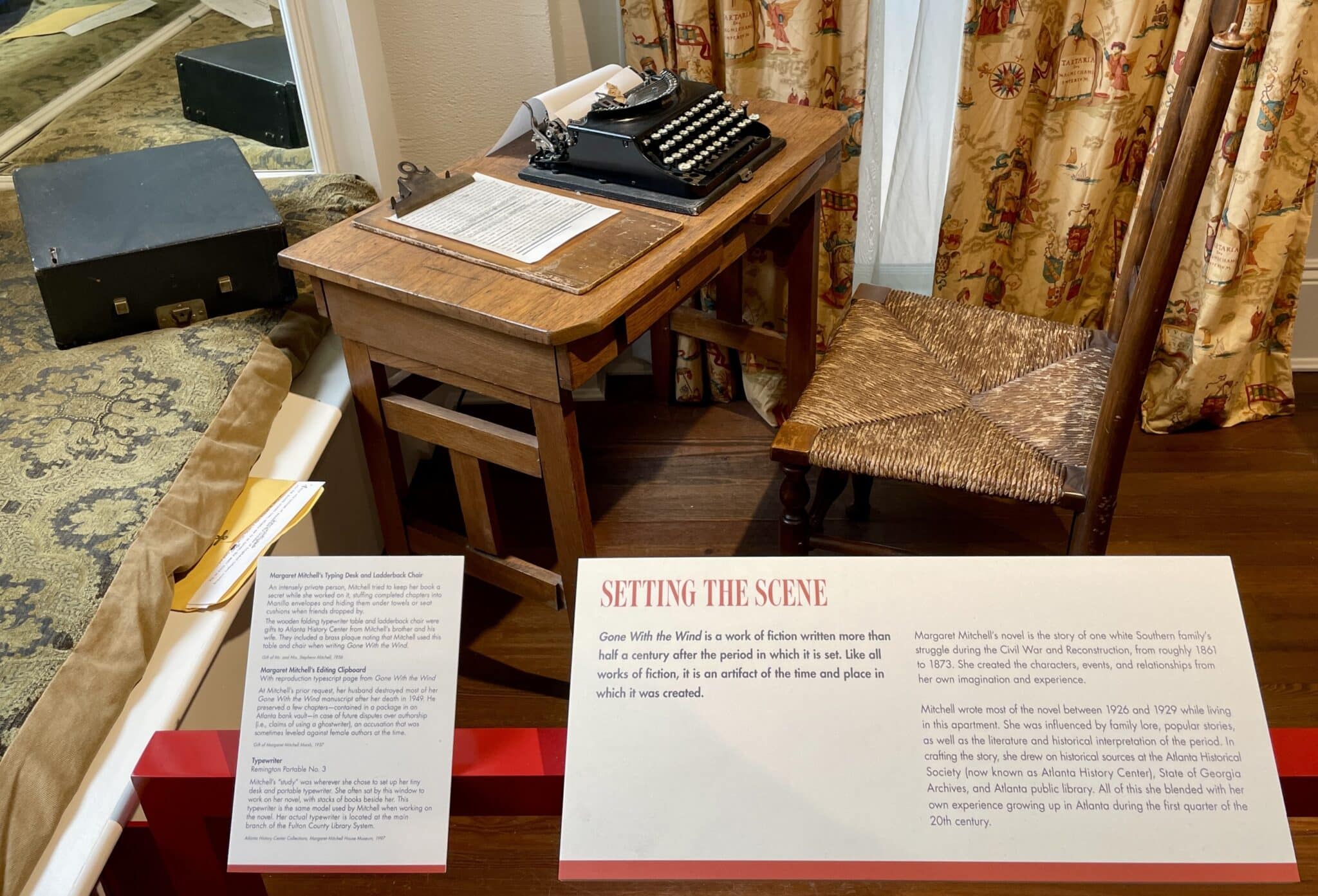

Of course, the museum is not only about the book’s controversies. It still tells the story of Margaret Mitchell’s life – her experience growing up in Atlanta, two marriages, journalistic career, secret writing of this novel, ultimate publication and fame, philanthropic efforts, and early death. She spent the first seven years of her marriage to John Marsh in this small, lower-level, two-room apartment she called “the Dump.” It was here that she wrote Gone with the Wind while recovering from an injury. The museum displays many items associated with Mitchell, including desk, chair, and a replica typewriter.

Back in January 2020, prior to the museum’s renovations. ECW’s Sarah Kay Bierle wrote about her visit to the Margaret Mitchell house in this blog post. I encourage you to read it to learn more about how the museum presents the story of Mitchell’s life. That part, I believe, remains much the same – though some of the panels may have added additional text. Panels now acknowledge the author’s biases resulting from being a fourth generation Georgian whose grandfathers both fought for the Confederacy, as well as from spending her entire life in Atlanta, where she grew up hearing glamorized stories of the Old South and was surprised at age ten to learn Robert E. Lee had been defeated.

I was surprised to learn Mitchell died on August 16, 1949, when she was just 48 years old, three days after being struck by a car while crossing the street with her husband. She was buried at Oakland Cemetery. Gone With the Wind is the only book she ever wrote. Efforts to preserve the deteriorating Crescent Avenue property where she had lived began in 1980. It was African American Mayor Andrew Young’s denial of a demolition permit in 1988 that kept the house from being destroyed.

Preservation efforts led by Atlantan Mary Rose Taylor began in earnest in 1991, and the Margaret Mitchell House and Museum opened in 1997. The building is now part of the Atlanta History Center Midtown. It reopened in July 2024, as detailed in this New York Times article, and I was happy to be able to visit in June. This newly renovated version is, I believe, worth a visit and does an effective job at addressing both the pros and cons of this memorable and impactful novel and film.

Endnotes:

- Austin, Elizabeth. “Why I Threw Away My Copy of Gone with the Wind.” washingtonmonthly.com, Washington Monthly, 11 June 2020, https://washingtonmonthly.com/2020/06/11/why-i-threw-away-my-copy-of-gone-with-the-wind/. Accessed 11 Oct 2025.

- Washington, Jr., Leon H. “Hollywood Goes Hitler One Better.” Los Angeles Sentinel [Los Angeles], 9 Feb 1939, https://www.friendsofthelincolncollection.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/LL_2002-Summer.pdf.

- Ridley, John. “John Ridley: Why HBO Max should remove ‘Gone With the Wind’ for now.” Los Angeles Times, 9 June 2020, https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2020-06-08/hbo-max-racism-gone-with-the-wind-movie. Accessed 11 October 2025.

- Wright, Rev. John Clarence. “Atlanta Baptists Rap Segregation, Dancing; Criticize GWTW Affair.” Atlanta Daily World [Atlanta], 20 Dec 1939, https://www.atlantahistorycenter.com/app/uploads/2025/08/Telling-Stories-Citation-Document-Public_Final.pdf.

Thank you, Tonya, for sharing this wonderful piece on the Mitchell Museum. I think that we always have to examine the context of the time when any particular piece of art is produced. GWTW in print and celluloid is very much a product of the height of the Lost Cause Mythology. In and of itself GWTW is a ripe subject for study in the way memory is created over time. Thank you again for a great piece.

I agree with Charles. I have wonderful memories of reading my mother’s 1937 reprint of Gone With the Wind one summer while I was in high school. Even then, I knew that the slavery presented in that book was unrealistic. Likewise with the movie. Still, both were products of their time and wildly popular. Both are American classics for better or worse. While I think articles such as Tonya’s are to be commended for pulling back the proverbial curtain, efforts to ban or shun these works are counterproductive and the proverbial slippery slope. Unlike the author cited in footnote 1, I am keeping my mother’s copy.

Always good to check sources: “Yes, Margaret Mitchell knew her grandmother, Annie Fitzgerald Stephens. Her grandmother was a major source of “eye-witness information” about the Civil War and Reconstruction, and Mitchell grew up hearing her stories.

Mitchell’s grandmother lived near her family in Atlanta, and her stories provided Mitchell with much of the inspiration for her historical fiction.” One person’s lived experience is opportunity for remote and uninformed criticism from many others, long after the fact. Good book on Mitchell: “Southern Daughter”, D. Asbury Prior. Good book on punitive Northern economic policies creating a Southern province, “Southern Reconstruction”, Phillip Leigh, and conditions of Reconstruction, “Sick From Freedom”, Jim Downs, Those are for starters.

I just watched the film – first introduced to me by my mother, the most non-racist person I’ve ever known – for the twenty-fourth time last week…still haven’t spotted a single racist thing in it, much less romanticizing the cause of fighting for one’s Constitutional rights. In this era of Maoist revisionism of American History, it is shocking and fascinating to read quotes like that from John Ridley – who, by the way, produced his own wildly inaccurate book and screenplay about the period. Read his words carefully – they are pure fantastical projection of something he wants ‘Gone With The Wind’ and the people of the South to have stated when in fact they never did:

“It is a film that…romanticizes the Confederacy…” At no part of the film is the Confederacy even discussed, except the brief speech by Rhett Butler noting how foolish secession, however legal, is because the South is vastly outnumbered in terms of people, money, weapons, etc. and doesn’t stand a chance of winning. “…continues to give legitimacy to…the secessionist movement…[which] was a bloody insurrection to maintain the ‘right’ to own, sell and buy human beings…” Is he sure? After all, slavery was legal and protected by the Constitution, was practiced in six states that remained in the Union up to December 1865, and the Congress did not get around to even finalizing a vote to end slavery until January 1865 – after three years and nine months of war. Had Ridley read even a single book about the war and the period, he might – might – have learned that the Federal government made exactly zero moves to end slavery prior to December 1865, and Lincoln himself publicly vowed to “bring the South back into the union with slavery intact.” Who on Earth ever rebelled against something that did not exist? “The movie…sentimentalize[d] a history that never was.” Really? Is he sure? He clearly demonstrates little knowledge of the times so it’s doubtful he can tell what was and was not history. Meanwhile, the film displays flawed humans who often act in capricious ways, or are cowards, or are mere ordinary folk struggling to survive in the midst of calamity, with, which Ridley totally missed, the black characters serving as the moral center of the story. Wow – it seems he’s a racist. “…it continues to give cover to those who falsely claim that…the plantation era is a matter of ‘heritage, not hate.’” So, people created huge farms because they were filled with hatred, not the drive to succeed as planters…incidentally, feeding the bellies in the North demanding food and tobacco, and the mills in the North and Europe demanding cotton – from which the North made ten times the profits than did the South.

It seems clear Ridley is amongst this crowd of haters who hate that which they do not know, anywhere and everywhere, because it is really a projection of their own self-hate – which explains the current attempt to destroy and rewrite American history – along with America itself. Remember, these are the same people who have piously informed us – while demanding total, undemocratic control of the government, that highways, the climate, and Covid are also racist. It is high time to expose and destroy their scamming of society, and render it to the dust bin of history along with their other, similar ideas – Socialism, Communism, National Socialism or Fascism, Militarism and Islamism.