Three Minutes of Fury: Col. R. E. Lee and the U.S. Marines Quell John Brown’s Rebellion

It’s the 250th birthday of the United States Marine Corps. The Continental Marines were established in Tun Tavern, Philadelphia on November 10, 1775. I worked as a civilian Marine from 2005-2008. Birthday celebrations were always fun because we got cake and got to see the base’s bulldog mascot, Molly – and as a Marine Corps Historian/Education Director, I passed down the legendary stories of Dan Daly, Smedley Butler, Rudy Contreras, Bill Westmoreland, Bill Weise, James Livingston, Steve Wilson, Bill Jayne, and many more.

When I was thinking of doing a 250th birthday article, I wondered if I could find some connection between their actions in the Civil War and current events. The light bulb went on when I re-read about U.S. Army brevet Col. R. E. Lee leading the U.S. Marines against John Brown’s insurgents holed up in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, October 17-18, 1859.[1]

Why were Lee and the Marines ordered to go in the first place? John Brown and his followers attacked a Federal armory at Harpers Ferry while attempting to incite a slave rebellion against Virginia. Federal troops were sent to protect U.S. Government property. It was also a situation that could’ve spread making it a national problem. The politicians took no chances.

How did Lee, a U.S. Army officer, get tapped to lead Marines? He was on unscheduled leave at the family home in Arlington, settling the estate of his late father-in-law, George Washington Parke Custis. Secretary of War John B. Floyd found out Lee was back. He was probably told by Lt. J.E.B. Stuart who happened to be home and was meeting with Floyd.

As soon as Floyd discovered Lee was in the vicinity, he sent him an urgent message on October 17: “a certain man named ‘John Brown’ had led seventeen other men, whites and blacks, into the town of Harper’s [sic] Ferry with the avowed purpose of liberating the slaves in that region, and supplying them with weapons from the United States Armory in that town.”[2]

The secretary of war directed Lee to go to Harpers Ferry, take command of 150 U.S. Army artillerymen, and seize Brown and his insurgents. There was, however, a catch. The artillerymen were making their way from Fort Monroe. It was about a 200-mile trek. Lee would get to Harpers Ferry long before the artillerymen. Waiting around wasn’t an option for President James Buchanan.

Buchanan told Floyd to send troops immediately! The secretary of war was at a loss. As far as he knew, he didn’t have any military personnel nearby. This was when Secretary of Navy Isaac Toucey stepped up. He knew a contingency of Marines was billeted at 8th and I Streets, Marine Barracks within the proximity of the Navy Yard, Washington City. Toucey ordered the Commandant of the Corps: “‘Send all the available marines at Head Quarters under charge of suitable officers, by this evening’s train . . . to Harper’s [sic] Ferry to protect the public property at that place, which is endangered by a riotous outbreak’” and report to the senior U.S. Army officer, Lee.[3]

Colonel Lee, still in civilian attire, and Lt. Stuart rode to Washington. The two first met with Secretary of War Floyd. The three then went to the White House. Buchanan provided Lee with a written proclamation of martial law if he needed it and assigned an aide to the colonel. He’d need one if there was going to be a fight. Stuart volunteered to assist as well. Lee and his small military staff met the 90 well-armed Marines near the railroad station at Sandy Hook, Maryland, just across from Harpers Ferry.[4]

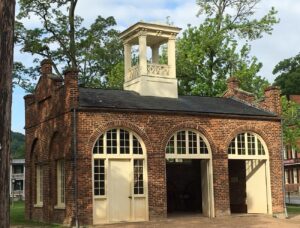

A briefing was given to Lee and the Marine officers the evening of October 17. Virginia and Maryland militia swarmed the town. Although unruly, drunk, and disorganized, the militia trapped John Brown’s force of about 16 men in a 30-by-35-foot stone building on the U.S. Armory grounds. The building had fire fighting equipment in it. Brown had taken several people hostage, one being a colonel on the Virginia governor’s staff and a relative of George Washington. The fighting would be in tight quarters. The assaulters couldn’t bombard the building for fear of killing hostages, nor did Lee want to risk obliterating the Federal property that they were sent to protect.

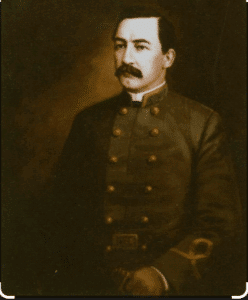

Lee was a deft diplomat when he wanted to be. He understood the potentially touchy federal-state relationship in this case. He first offered the assault to the Maryland and Virginia militia officers; both declined. I’m surprised Lee even asked, but he turned to the lead Marine officer, 1st Lt. Israel Greene. He was smartly adorned in his dress uniform. “Would the Marines storm the engine house?” The adrenaline rushed through the young Marine. Greene whipped his cap off and thanked Lee for the offer.[5]

The tactical approach was straightforward. On the morning of October 18, Stuart approached the engine house under a flag of truce and delivered an ultimatum to Brown’s radicals: surrender or the Marines would take them by force. Brown refused. Stuart raised his plumed hat, signaling Greene that his men were up. Much like Admiral Horatio Nelson’s dogma, the Marines’ goal was to move fast, close with the enemy, and violently engage to suppress the agitators.

Getting into the engine house proved tougher than it sounded. Three Marines smashed the double-doors with sledgehammers and tried busting their way through the doors.[6] When this didn’t work, Greene adapted, used his ingenuity, and directed his men to use a fire ladder lying outside the fire house as a battering ram; that worked. One of the doors splintered. The storming party entered the smoked-filled room with bayonets fixed. Their U.S. Model 1842 muskets were unloaded for fear of injuring the hostages.

Three minutes of fury ensued. Two Marines bayoneted one Brown follower hiding under a fire engine. Another Marine disarmed and took out an insurgent by pinning the man against the stone wall with his 17.5-inch blade. Greene wielded his dress sword and slashed at Brown. The blade cut his neck, but didn’t kill him. Bleeding, John Brown surrendered. The young lieutenant then ordered his leathernecks to stop stabbing the combatants and start taking them prisoners.

The operation was a complete success. All ten hostages were rescued unscathed.[7] The Marines counted two casualties; one received a fatal wound. John Brown’s raiders suffered ten killed, six survived. He and the others were found guilty of murder, conspiring with slaves to rebel, and with treason against Virginia. All were hung.

It was that fateful October 1859 when the gods of war brought together the lethal combination of Colonel R. E. Lee and the U.S. Marine Corps. Working together, the contingency protected Federal property, saved the hostages, and swiftly crushed the violent insurgency. Lee was impressed with the Marines. He wrote in his after-action report: “I must also ask to express . . . my entire commendation of the conduct of the detachment of Marines, who were at all times ready and prompt in the execution of duty.”[8] Happy 250th Birthday Marines! Semper Fi –

[1] Whether you think John Brown had, or didn’t have, a just cause, he and his men were insurgents per military and political insurgency/counterinsurgency manuals. Abolitionist Brown, five of his sons, and three other men murdered five proslavery men at Pottawatomie Creek, Franklin County, Kansas, May 1856. See https://civilwaronthewesternborder.org/encyclopedia/pottawatomie-massacre.

[2] Bradley Gilman, Robert E. Lee, 1915, 78. Lieutenant JEB Stuart delivered that message.

[3] Bernard C. Nalty, United States Marines at Harper’s Ferry and in the Civil War, History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Washington, D.C. (1983), 2. The Marines didn’t receive their mandate to guard all Federal buildings and embassies and White House until after World War Two, see Marine Security Guard, 1948. That’s why the President can directly command the Marines during an emergency, and why the Marines can be called out to assist during riots such as the Los Angeles riot in 1992 and 2025.

[4] Lee thought he and the Marines would travel via railroad together, but the Marines had left Washington on an earlier train. Marines don’t like to wait around once given the go.

[5] Nalty, 5. During the Civil War, Greene joined the Confederacy. He survived the war.

[6] A reenactment photograph can be seen in Mac Caltrider’s article: https://www.mca-marines.org/leatherneck/rushing-like-tigers-the-marines-at-harpers-ferry/.

[7] Ibid.

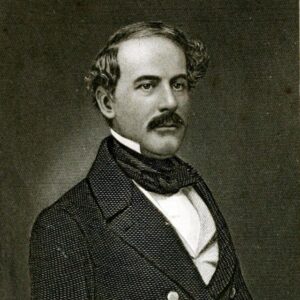

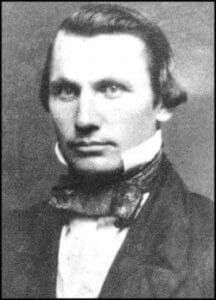

[8] Nalty, 1. I think the Marines were the best tactical choice for this operation. They were trained to protect and capture ships which required fighting hand-to-hand in close quarters. This takes skill. If the militia had gone in I think several hostages would’ve been killed. Illustrations: 1. Marines Storm John Brown’s Insurgents, Harpers Ferry, October 17, 1859, painting by Porte Crayon published in Harpers Weekly. 2. R. E. Lee: NPS; 3. Stuart, NPS; 4. Engine house, Harpers Ferry, NPS; 5. Greene, https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/Fortitudine%20Vol%2034%20No%204_1.pdf; 6. U.S. Marines circa 1850s, https://www.wearethemighty.com/mighty-history/marine-corps-during-the-civil-war/; 7. Model of Marines storming engine house https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/john-browns-bloody-abolitionist-crusade/

thanks JoAnna … I always wondered how that unlikely trio — Colonel Lee, Lieutenant Stuart and a platoon of marines — came together and ended John Brown’s insurrection … now I know thanks to your wonderful essay.

And speaking of the USMC and history, you have the best museum of all the military services … if you live in the DC area, it was worth the short trip down I-95 to Quantico … thanks again!

“Three Minutes of Fury” isn’t history—it’s propaganda. Brown wasn’t an insurgent. He was a revolutionary. And the Marines? They didn’t save hostages. They saved slavery. #ColonialWhitewash #BlackRevolution

Agree. This article is wrong on so much. It should not earn a place on “Emerging Civil War.”

They call Smedley Butler a legend. But they won’t quote his truth: “War is a racket.” He didn’t fight for freedom. He fought for corporations. That’s the real legacy they bury.

What about Chesty Puller and John Basilone?😄

Well-told story. Thank you.

You used the phrase “unscheduled leave” in reference to R.E. Lee. You are not suggesting that he was AWOL, are you?

At his trial, Brown argued that the treason against Virginia charge was legally merit less because he owed no loyalty to Virginia. As a matter of law he was correct, but that provided no defense to the other charges.

You’re welcome! No Lee wasn’t AWOL. I meant he was not expecting to come home at that time as far as I recall. The book “Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee” might discuss the timeline. The book is edited by Lee’s youngest son and is available on google books. I don’t know much about Brown’s trial. Brown and his group had murdered one or two people at Harpers Ferry when Brown first got to Harpers Ferry. Ironically, one of those men murdered by Brown’s group was a freed black man. Brown was also a religious zealot, complete nutter. He thought he had a mandate from God to free all the slaves and murder people in the process. ECW has done several good blogs on Brown.

It’s always thrilling to read of the capture and execution of John Brown the domestic terrorist by the men who became, respectively, the greatest general America ever produced and the greatest mobile warfare soldier America ever produced, Robert Lee and J.E.B. Stuart. I am currently at work on a screenplay about the incident for a major motion picture; we’re talking with Michael Shannon to portray Brown. But remember, the captured terrorists were hanged, not hung. We reserved “hanged” for humans, while “hung” is used for paintings, pictures and porn stars.

You should meet my old pal EP Schafer. Wonder what happened to that guy.

Thanks for the article. It seems you picked a pivotal event in history that some of the famous people of the times ended up there! Stonewall Jackson and John Wilkes Booth were both at the execution of John Brown. It’s believed Booth learned from being there that he saw how one man could change history. Thanks again, I’m sure it would been easier writing about Iwo Jima and the sacrifices made by the Marines there!

Well-written article. Of course, John Brown is a controversial figure, whether you consider him to be a revolutionary or insurgent, and you could go in so many different directions with this topic. However, from a purely military and tactical lens, I enjoyed learning how Lee, Stuart, the Marine force, and the Virginia and Maryland state militias effectively worked together, all under the guiding leadership of the Lee himself.

Well written article. Whether you consider John Brown to be a revolutionary or an insurgent, with a topic like this, you could obviously go in so many different directions. However, with a purely military and tactical focus, I really appreciated and learned more about how Lee, Stuart, the Marine force, and the Maryland and Virginia militia forces effectively collaborated together under the deft leadership of Lee.