“…and soon after abandoned its guns.”

In the annals of the Civil War few units had as short of a career as the 13th Ohio Battery. They were one of five confirmed Ohio batteries that fought at Shiloh. Every one of them was engaged. But while the 5th, 8th, and 14th batteries, and Battery G of the 1st Ohio Light Artillery survived the battle and served to war’s end, the 13th Ohio Battery did not.

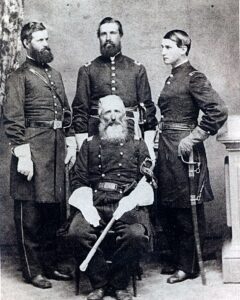

The 13th Ohio Battery was formed from men from central Ohio, mostly from Champaign, Hardin, Logan, Shelby, and Union Counties. Their commander was Captain John Blymier Myers. He left no memoirs, letters, or even a report. He also did not write to the newspapers about Shiloh. However, he likely had political connections, namely to Benjamin Stanton, Ohio’s then lieutenant governor.

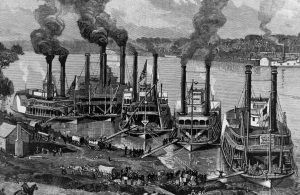

The battery mustered in at Camp Dennison near Cincinnati on February 16, 1862, then went to St. Louis. The battery left St. Louis on March 17. Things were already looking inauspicious. On the way, their steamboat sprang a leak and was beached. Despite this delay, the battery arrived at Pittsburg Landing on March 20.

Pittsburg Landing was a flurry of activity. New units arrived nearly every day. There was also a transfer of command as Ulysses S. Grant took over for Charles F. Smith. Grant was ill (he soon recovered), and Smith was ailing from a leg injury that eventually claimed his life. The result was the 13th Ohio Battery arrived in the midst of a command change where the two senior officers were in poor health. In the confusion, the 13th Ohio was seemingly lost in the shuffle and was unattached. The 13th Ohio Battery was also poorly trained, and sickness plagued the battery. Not until a week before Shiloh was the regiment at last attached to Stephen Hurlbut’s division.

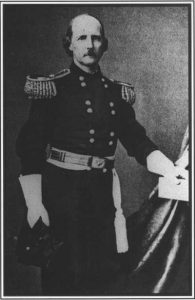

Hurlbut was a Charleston native involved in the slave trade, something he later tried to hide. After losing money in gambling, he cheated at cards and fled in disgrace. He became an Illinois Republican who Lincoln declared “the ablest orator on the stump that Illinois had ever produced.” While he was good at drill, he was often drunk and known for cruelty. Isaac Pugh, commander of the 41st Illinois, wrote that Hurlbut was “…drunk all the time.” Warren Olney of the 3rd Iowa recalled that he once saw Hurlbut “so drunk he couldn’t sit upright.”

On April 6, the Rebels surprised Grant’s army. Hurlbut was to the east of William Tecumseh Sherman’s division and northeast of Benjamin Prentiss’s division. Both units came under attack. Hurlbut shifted to come to Prentiss’s aid, but before he could, his division was shattered. These refugees ran past Hurlbut’s forces. When one staff officer asked, “What are you running for?” the soldier answered, “Because I can’t fly.” As the 3rd Iowa came up, one man yelled to them, “Don’t go out there-they give hell! We are all cut to pieces.” Hurlbut went to the front in full dress uniform, complete with yellow sash, epaulets, and sword. During the carnage, Hurlbut stayed calm. When a staff officer asked Hurlbut to go to the rear he replied, “Oh, well, we generals must take our chances with the boys.”

Jacob Lauman’s brigade deployed to the right near where Prentiss was reforming his command. The 2nd Michigan Battery unlimbered in front of the battle line on the north end of Sarah Bell Field and opened fire. Hurlbut then had Nelson G. Williams’s brigade plunge across Sarah Bell Field. He ostensibly did this to give Prentiss time to reform and to aid David Stuart’s brigade, who was to his left at Larkin Field. Hurlbut ordered, Mann’s Missouri Artillery (Battery C 1st Missouri), command by Lieutenant Edward Brotzmann, to support Stuart, who had no artillery.

Hurlbut’s fire was heavy and caused the Rebels to pause. Daniel Adams’s brigade could not advance under such a fire. The Confederates brought in two batteries: Washington Artillery (Georgia), led by Isadore P. Girardey, and an Alabama battery, led by Felix Huston Robertson. Meanwhile, one of Hurlburt’s staff told Myers, “Captain, Gen. Hurlbut wants you to go into action quicker than hell can scorch a feather!” Myers complied with “Yah! Yah!” and the 13th Ohio to the right of the 2nd Michigan. They were without direct support in an exposed position.

Robertson opened fire, although whether Myers at that moment was only just arriving or had time to place his cannon has been debated ever since. At any rate, the 13th Ohio lost several men in Robertson’s third shot. Cuthbert Laing of the 2nd Michigan reported, “one of their caissons was shivered to pieces, and the horses on one of the guns took fright and ran through our lines.” Olney observed that Myers’s “battery was knocked into smithereens. Great limbs of trees, torn off by cannon shot, came down on horse and rider, crushing them to earth.” They were also under fire from elements of the 22nd Alabama.

It was all too much for Myers and the 13th Ohio Battery. Williams reported that they did not even fire back. The men fled for the rear, leaving five of their cannon to the Confederates, while the sixth was brought to Pittsburg Landing. The untrained horses were blamed by the battery for the disaster. Brotzmann’s battery was recalled from Larkin Field in order to make up for the loss, depriving Stuart of artillery; this had dire consequences when the Rebels attacked Stuart’s camp. Hurlbut had ten volunteers from the 2nd Michigan and Brotzmann’s battery try to save Myers’s cannon. They soon came under fire from the 22nd Alabama and fell back.

Losses piled up from Rebel cannon fire. Benjamin Bristow was struck in the head by shrapnel, although he stayed in command of the 25th Kentucky. However, William B. Wall lamented that he was “insensible the remainder of the day. His hearing is seriously, and I fear permanently, injured, and the spinal column injured.” A cannonball passed through Williams’s horse. Its carcass pinned him as the horses from the 13th Ohio galloped by. Brigade command went to Pugh; Williams never again led men into battle.

The Federals on the south end of Sarah Bell Field fired wildly. When the Confederates opened fire on the right, the 41st Illinois let off a full volley into the woods, killing only a cow. Soon nearly all of Pugh’s brigade were opening up. George Swan of the 3rd Iowa boasted, “The earth trembled as we fired volley after volley, well directed, into the rebel ranks, which mowed them down like grass before the scythe.” It was an exaggeration. The Rebels did not report heavy losses. Pugh, fearing his left flank was in danger, fell back, but not before he directed some men to spike Myers’s cannon.

The battle was not wholly over for the 13th Ohio Battery. At Pittsburg Landing, Grant and James Webster formed a last line of defense centered around artillery. Among the last line’s some fifty guns, the lone surviving cannon of the 13th Ohio was in place, although where exactly is unknown. Regardless, it would be the battery’s last action as any kind of coherent force.

The Union won Shiloh, but the 13th Ohio Battery received no respite. Rain, poor food, and illness made camp miserable after Shiloh. Hurlbut described the 13th Ohio as “cowards, who disgraced their state and their flag,” and called Myers “scum.” Amory K. Johnson, commander of the 28th Illinois, called them “cowardly and disgraceful.” Olney recalled, “But how those astounded artillery men – those of them who could run at all – did scamper out of there. Like Mark Twain’s dog, they may be running yet.” After the battle, Hurlbut oversaw the battery’s dissolution. It’s canon, and many of the men were transferred to the 14th Ohio Battery, which later distinguished itself at Resaca and Nashville. Some were sent to the 7th and 10th Ohio Battery. Hurlbut stripped Myers of his rank. The fact that the crew retreated almost en masse represented what might be the worst performance by a single battery in the entire war. No battery certainly had a shorter career under fire. As Olney mused, “it was literally wiped out then and there.”

The men of the 13th Ohio Battery were not happy with their treatment. Letters of protest filtered back home. Charles Milton Adams described his new compatriots in the 10th Ohio as mostly “pretty hard, nearly all use profane language, and nearly all are gamblers, the consequence is there is a great deal of quarreling among them and they are not so well drilled as they should be. For my part I hope it will never be my lot to go into an engagement with them, and I hope that matters will soon be arranged so that I can get out of their company.” These letters were published in various Ohio newspapers, and as many questioned why the army was surprised and why such terrible losses occurred, men looked for guilty parties.

Some Ohio politicians and newspapers accused Hurlbut of poor placement and trying to cover for his errors by blaming the 13th Ohio. Benjamin Stanton was the most aggressive in this regard. He wrote, “he seeks to throw the responsibility upon the officers and men of an undisciplined Artillery company, who were left wholly unprotected by the proper support of infantry, and when their only alternative was retreat or surrender. And these officers and men, it is now said, are to be mustered out of service; and sent home in disgrace. while this blundering ignoramus of a General is suffered to strut around in his brass buttons and epaulettes as though he had inherited the genius and had courage of Napoleon.”

Hurlbut told Grant the 13th Ohio was placed on a reverse slope, and Myers was to blame for its exposed position and complete collapse under fire. Grant backed up Hurlbut. Indeed, Hurlbut had greater friends than Stanton. Halleck, Grant, and Sherman liked him, but more to the point, he was Lincoln’s man. Stanton’s attacks failed to restore Myers or the battery. It also helped that Hurlbut did quite well during the rest of the battle.

After the war, Robertson came to the defense of the battery, declaring it was poorly placed. Robertson believed Hurlbut’s position was not fully formed, and he blamed the 13th Ohio Battery’s demise on his mismanagement. While it did not excuse the entire battery running, Hurlbut’s opening action at Sarah Bell Field was not his best showing at Shiloh. In addition, the battery was poorly trained, led, and came to the front in a confused battle, with hundreds of panicking men running for the rear. Perhaps they deserved another chance at least. The 71st Ohio was granted that and did well at Nashville.

Although initially included in the budget proposed by the Ohio Shiloh Commission, there is no monument for the 13th Ohio Battery, the only one among Ohio units. Even the 71st Ohio has a monument. There is a tablet for the 13th Ohio’s second campsite and for where they were briefly under fire. Its words are not kind and represent for many the final word on the 13th Ohio: “This battery took position here at 9 a.m. April 6, 1862, and soon after abandoned its guns.”

Harsh. Too bad about the 13th. But wonderful comment by the fleeing soldier who could not fly. Thank you for sharing.

Well written account of a very hard luck unit. Thank you.

Good article. The 13th was certainly a hard luck battery.

It seemed a perfect storm of factors, including being poorly trained and led, many men being sick, enduring a delay in arriving at Pittsburg Landing, and they were in an exposed position with no infantry support. Thank you for the article and for doing the men of the 13th Ohio Battery the justice of at least providing some explanation of their actions, that goes beyond the one sentence on the marker.

Referring to a previous blog, this is why it would be helpful were the cannons, trees, and horses able to talk. I can’t help the feeling that these men had been screwed from the start. Too many commanders trying to cover their asses. Just come clean that it was an ill advised deployment, take it as a lesson learned, and move forward. Those poor souls seemed to have been left out to dry. That marker, addressed as such, is really bothersome and a tad shameful. The Union got caught with their pants down that day.