Shifting Sands of Memory: Civil War Filmography Since 2008

In his seminal work on the relationship between Civil War filmography and memory, Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten, Gary W. Gallagher laid a foundation for how to view the intermingling of those two fields. He observed four main fields of historical interpretation in public memory – The Lost Cause, the Union Cause, the Emancipation Cause, and the Reconciliation Cause – and proceeded to see how those various strands interacted with filmmaking to produce Civil War movies. Published in 2008, Gallagher analyzed some of the most famous Civil War movies with this method, including Glory, Gettysburg, and Cold Mountain.[1] Since then, however, several more major Civil War era films have been produced, allowing for another evaluation to be done using Gallagher’s method.

The four historical interpretations that Gallagher identifies should be addressed first. The Lost Cause refers to, in his words, “a loose group of arguments that cast the South’s experiment in nation-building as an admirable struggle against hopeless odds, played down the importance of slavery in bringing secession and war, and ascribed to Confederates constitutional high-mindedness and gallantry on the battlefield.”[2] The sole explicitly Confederate perspective among the four interpretations, it arguably holds the deepest roots in film history, with notable films such as Birth of a Nation (1915) and Gone with the Wind (1939) being among its progeny.[3] As the 20th century progressed and many of its foundational arguments were increasingly rejected, however, its prominence waned, and it slipped into the background. Among more recent films, Gallagher identifies Gods and Generals (2003) as the primary film fitting within this category.[4]

The Union Cause, meanwhile, is summarized by Gallagher as, “fram[ing] the war as preeminently an effort to maintain a viable republic in the face of secessionist actions that threatened both the work of the Founders and, by extension, the future of democracy in a world that had yet to embrace self-rule by a free people.”[5] Despite it being the primary viewpoint of the majority of white Union soldiers and civilians during the war, its portrayal is strikingly absent throughout the entirety of Civil War filmography.

Gallagher attributes this to two main causes. During the hey-day of the Lost Cause interpretation in the first half of the 20th century, the Union Cause’s direct contradiction to it caused it to be overlooked. In the latter half of the 20th century, America’s experiences with the Vietnam War left an environment where America’s armed forces were viewed in a decidedly more negative light. Consequently, an interpretation based on providing the perspective of those soldiers, even from the Civil War era, once more struggled to gain traction.[6]

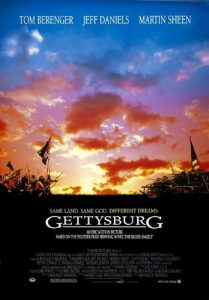

Instead, the downfall of the Lost Cause left a void primarily filled by two newer interpretations of Civil War memory: the Emancipation Cause and the Reconciliation Cause. Gallagher describes the former as “interpret[ing] the war as a struggle to liberate 4 million slaves and remove a cancerous influence on American society and politics.”[7] Although widely accepted by the African-American community from the time of the conflict onwards, it struggled to gain broader traction when competing against the Lost and Union Cause traditions. As both of those movements declined in movie-making popularity, however, Emancipation stood as the primary beneficiary. Initially emerging as an element in some films such as Shenandoah (1965), the release of Glory (1989) catapulted it into the mainstream. Since then, almost every major Civil War film, from Gettysburg (1993) to Ride with the Devil (1999) to even Gods and Generals have acknowledged the tradition.[8]

Finally, there is the Reconciliation Cause tradition, explained as “an attempt by white people North and South to extol the American virtues both sides manifested during the war, to exalt the restored nation that emerged from the conflict, and to mute the role of African Americans.”[9] While all three other traditions emerged almost immediately following of the Civil War, Reconciliation necessitated time for white hostilities to cease in order to develop. Once this did occur, however, Reconciliation became a very useful tool for promoting a unified American identity and nationalism, one that had been tested and tried by a “brothers’ war” but ultimately survived. Emerging with such films as The Red Badge of Courage (1951), it continued into a more recent era with Gettysburg.[10]

At the time of Gallagher’s book, the state of the interplay between Civil War filmography and memory saw a clear predominance of the Emancipation tradition, although Reconciliation played a substantial role as well. The Lost Cause had receded into a shadow of its former preeminence, while the Union Cause remained as unacknowledged as ever.

But with almost two decades having passed since his research, how has this relationship developed? Following his standard, this will be determined by evaluating the major Civil War films since 2008. Defining a major Civil War film as one that focuses predominantly on the war as well as having a budget of over ten million dollars, there are five movies to assess: The Conspirator (2010), Lincoln (2012), Copperhead (2013), Free State of Jones (2016), and Emancipation (2022).

In line with the Emancipation Cause interpretation, there is Lincoln, Free States of Jones, and, predictably, Emancipation. All three movies address slavery and its central role in the conflict. Lincoln recounts the efforts of the eponymous president to pass the 13th Amendment in the closing days of the Civil War, as well as depicting African-American soldiers and the Confederate resistance to abandoning slavery.[11] Free States of Jones, meanwhile, highlights a pro-Union rebellion within the Confederacy led by Newton Knight. The film highlights the complex interplay that slavery played in Southern society during Civil War and Reconstruction. Knight’s rebellion is depicted as being in part driven by runaway slaves, and the freedmen experience in Reconstruction is prominently featured as well.[12] Finally, Emancipation fits within the interpretation the closest of all, depicting a broadly fictionalized version of the life of Peter, the slave made iconic by the photograph of his whip-scarred back. Slavery and freedom are the central elements of the narrative, as Peter flees from his work in a Confederate military encampment to eventually join the African-American 1st Louisiana Native Guard in the Union Army.[13]

Elements of the Reconciliation Cause predominate the other two films. The Conspirator tells the story of Frederick Aiken and his legal defense of Mary Surratt over her involvement in the Lincoln assassination. Aiken is presented as the epitome of the Union soldier, with his real life Confederate dalliances notably omitted from the screenplay.

As this bastion of Union values gets to know Mary Surratt, the representative of the Confederacy, they grow closer together and reach a mutual understanding. The Lincoln assassination is presented in a negative light, but so is the overwhelming force and questionable tactics deployed by the prosecution in the trial of the Lincoln conspirators.[14]

Copperhead, meanwhile, is a fictional story about a Copperhead named Abner Beech from New York. His primary antagonist is the fervent abolitionist and religious zealot Jee Hagadorn, but their two children have a romantic relationship that can be interpreted as Union and Confederate-adjacent representatives joining together. The film also contains some allusions to the Lost Cause perspective, such as the film’s primary abolitionist character being a raving, uncompromising, and violent man.[15]

From this, we can see that many of the trends that Gallagher highlighted in 2008 still continue to the present. The Emancipation and Reconciliation Causes remain the predominant interpretations of the war in film. The Lost Cause is relegated to the sidelines, and the Union Cause receives hardly any attention at all. There is a notable departure from Gallagher’s era of analysis, however. Of the fourteen movies he analyzes in his book, eight primarily and/or extensively feature the Confederate perspective and characters (Gettysburg, Sommersby, Pharoah’s Army, Ride with the Devil, Gods and Generals, Cold Mountain, C.S.A.: the Confederate States of America, and Seraphim Falls).

In contrast, of the five films discussed here, none are shot from the Confederate perspective. Indeed, even if one were to loosen the definition of “major Civil War film”, Field of Lost Shoes (2014) is the only Civil War film of any notoriety to be from that perspective.[16] From both a financial and artistic perspective, for films must account for both, this makes sense. As portrayals of the Confederacy grow increasingly taboo and scorned in modern society, the risk of producing a film overly sympathetic to their cause is certainly worrisome to any production company hoping to turn a profit. Similarly, with the primary Confederate interpretation of the war largely discredited and dismissed and no new Southern-originating consensus to replace it, there is little material for the story-tellers of the film industry to work with to tell their stories. Nevertheless, as time continues its march onwards and shifting historical interpretations change alongside it, the relationship between Civil War filmography and memory is sure to keep developing as it has always done.

Endnotes:

[1] Gary W. Gallagher, Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood & Popular Art Shape What We Know about the Civil War (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 1-14.

[2] Ibid, 2.

[3] Brian Steel Willis, Gone with the Glory: The Civil War in Cinema (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc, 2007), 7-17.

[4] Gallagher, Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten, 42-89.

[5] Ibid, 2.

[6] Ibid, 114-134.

[7] Ibid, 2.

[8] Ibid, 92-106.

[9] Ibid, 2.

[10] Ibid, 106-114.

[11] Lincoln, directed by Steven Spielberg (2012, Touchstone Pictures).

[12] Free State of Jones, directed by Gary Ross (2016, STX Entertainment).

[13] Emancipation, directed by Antoine Fuqua (2022, Apple TV+).

[14] The Conspirator, directed by Robert Redford (2010; Lionsgate).

[15] Copperhead, directed by Ron Maxwell (2013, Film Collective).

[16] The Beguiled (2017) is also technically a film primarily featuring the Confederate perspective, but it is arguably more of a thriller film that could have been set in any war than an incisive reflection of the Civil War in particular.

I don’t know if Gallagher talks about this, but one of the reasons I think American films tend to focus on the Confederate or ex-Confederate perspective is that American culture tends to valorize the underdog, the loner, and villainize the powerful. Glory succeeded as an Emancipation film because it was about a group of underdogs fighting against not just the Confederacy but also against a racist federal bureaucracy. Characters who are defeated and have to struggle to get back up again make a more compelling story.

That’s a really interesting insight. I suspect there is much truth to that analysis.

It’s ironic that the Union Cause perspective has largely been left out when it is the most accurate of the 4–as Gary has discussed in “The Union War” and in many lectures and articles.

Great article, many thanks!

But what about The Horse Soldiers, my favorite terrible Civil War movie … and the leads are staunch Union men fighting in the Western Theater… no southern stars in this one other Constance Towers as sappy southern belle who falls for a fifty-year-old John Wayne playing Union LTCOL Benjamin Grierson … and don’t forget the handsome Robert Holden playing Wayne’s dedicated and selfless surgeon … and i say terrible because it gets all the Grierson Raid history wrong and the fighting in a fictional town is goofy … but it’s got several hundred extras playing Union cavalrymen who are mostly properly uniformed, armed and mounted — very cool … i watch it everytime it comes on the old TV!

Thank you! I enjoyed The Horse Soldiers as well. It’s far from a great work of historical accuracy, but it is a fun film for a Friday night. In his book, Gallagher places the movie within the Reconciliation tradition. Especially considering the romantic plot between John Wayne’s Union and Constance Towers’s Confederate character, I agree with that assessment.