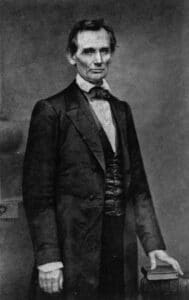

Lincoln’s “Right Makes Might”

Lately, there has been a lot of talk surrounding the principle of “might makes right” and its place in American politics. Lincoln had a few remarks to make on that ancient aphorism and its relationship to slavery in his Cooper Union Address on February 27, 1860.

In early 1860, Lincoln’s presidential candidacy was by no means assured, but threats of secession from Southern states had led the country to the precipice of civil war. His speech at the Cooper Union secured his place on the national political stage. In it, Lincoln asserted his firm belief that slavery should not spread to the Western territories, and the Federal government had the legal and moral right to stop it. According to Lincoln, the prohibition of slavery in the territories was the nation’s ethical imperative and hinged upon his belief that enslavement constituted a moral evil. “If slavery is right,” Lincoln opined, “all words, acts, laws, and constitutions against it, are themselves wrong, and should be silenced, and swept away.”[1]

Therefore, slavery’s existence and expansion could not be justified by the South’s—or the nation’s—ability to maintain it. Rather, Lincoln inferred that the death of slavery should be accomplished with a commitment to justice, not power.

The Illinois lawyer closed his Cooper Union Address that day with what has become one of his most oft quoted lines: “Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.”[2]

Here, Lincoln inverted the age-old principle of “might makes right,” instead arguing that righteousness itself generates strength. He knew that history often favored brute force, but he also believed Americans should work to reverse this, building their strength on the foundation of what is morally correct, like the principle of equality.

Indeed, Lincoln believed wholeheartedly in the rule of law over sheer power.[3] Even when he, as president, exercised broad executive powers in suppressing the rebellion, he convened Congress to seek legislative approval, demonstrating his firm conviction that the republic’s strength is only derived from consent.[4]

Lincoln also maintained a sort of religious commitment to the rule of law. “Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well wisher to his posterity, swear by the blood of the Revolution, never to violate in the least particular, the laws of the country; and never to tolerate their violation by others,” he said in his immortal Lyceum Address.[5] That even included a rejection of civil disobedience to law, which Lincoln saw little place for within the confines of democracy. If the republic’s laws were unjust, the only solution, in Lincoln’s mind, would be to repeal them legally and lawfully.[6]

That’s why law must, in Lincoln’s eyes, be grounded in morality—or mores, as Alexis de Tocqueville would call them.[7] Without mores, democracy is hollow. That, in part, is what caused Lincoln to acutely question the morality of slavery in his Cooper Union speech and denounce might over right.

In fact, that faith in right over might certainly guided his commitment to democracy and should guide our own.

Notes:

[1] Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 3, (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 549.

[2] Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 550.

[3] Allen Guelzo, Our Ancient Faith: Lincoln, Democracy, and the American Experiment (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2024), 42.

[4] Daniel Farber, Lincoln’s Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 162.

[5] Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 1, (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1953), 112.

[6] Guelzo, Our Ancient Faith, 42.

[7] Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, ed. H.C. Mansfield and D. Winthrop (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 292, 294.

So if the Federal Government was making war on slavery, what was the date Congress declared war? What was its accompanying statement about this war on slavery? If that Government and President Lincoln were so adamant about making war on slavery, why did they not, with the total absence of Representatives and Senators from the 11 seceded states, except for Senator Johnson of Tennessee, immediately amend the Constitution to abolish slavery? It would have been easy – they could have done it in a week. Yes, they didn’t get around to it until January 1865. Meanwhile, why did this anti-slavery Government allow five states in the Union to practice slavery throughout the war – and add a slave state to the Union halfway through the war. Odd. Odd indeed…

“[…] And the war came. One-eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it.

Neither party expected for the war the magnitude or the duration which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding […]”

– Abraham Lincoln, Second Inaugural Address, March 4, 1865

I’m not sure what’s odd about it. If you’re suggesting that the North was not of a single, monolithic mind in opposition toward slavery, then I certainly agree with you. I wouldn’t consider the Federal government “anti-slavery” until it adopted and ratified the 13th Amendment, whose only mention of slavery was its absolute prohibition. And the United States government has gone to war many times without declaring it.

Good stuff. Thanks. If I get Lincoln’s Cooper Union address clearly, if driving a car is legal, all red light cameras are themselves wrong and should be swept away? He’s got my vote.

Haha that’s an interesting way of looking at it!

Thanks, Evan, good piece. I’ll add that almost a year earlier, in an April 6, 1859 letter to a Republican meeting in Boston, chaired by former Mass. governor, George Boutwell, Lincoln made one of his most famous pronouncements about slavery, “he who would be no slave, must consent to have no slave. Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves; and, under a just God, can not long retain it.”

A great quote for sure. Perhaps a “golden rule” of sorts for democracy?

Yet another attempt to justify Lincoln’s War with wordsmithing. “Right makes might” is laughable because it justifies abrogation of the fact that the essential nature of the Constitution and our institutions is to abide by the law, which Lincoln, for many convoluted reasons, did not. Re the territories, the Confederacy gave up any involvement with them by seceding, so that was rather moot point at the time. I suggest “The Frontier Against Slavery”, Berwanger (used copies available online) for a PhD level and eye-opening discussion of that issue. Re slavery in general, good try but the institution itself was at issue only as competition to the wage labor of the North, including that of millions of recent immigrants. That is a long discussion, but I suggest “Empire of Cotton”, Beckert, for a PhD level dissection of the global forces surrounding US cotton production at the time. For the real cause of a leap to action by Lincoln, I recommend taking a look at US Treasury Reports (Sources of Revenue), 1850-1860. Loss of tariff revenue was already a problem; the diversion of imports to Confederate ports with free trade would have required implementing an income tax, not at all attractive to Northern industrialists. Lincoln’s self-exculpatory remarks at Cooper Union confirms the adage that hindsight is better than foresight; he chose a “quick and easy War” rather than display one shred of diplomacy and statesmanship, with dire results, both short term and long term. There was nothing about it that justifies sanctimonious platitudes.

I don’t think the principle of “right makes might” at all contradicts the nature of the Constitution or the rule of law, and I think Lincoln would have agreed with you on the importance of the rule of law (Re his opposition to civil disobedience). Berwanger’s The Frontier Against Slavery is a venerable, if antiquated, study, but I don’t think it proves the Confederacy abandoned their slave-holding interests in the West after secession. While competition to the wage labor of the North was certainly an issue at hand, it was not the only reason slavery was debated in the halls of Congress and across the country for nearly seven decades before the Civil War. As for the long-refuted tariff argument, look no further than the secession ordinances to see the real cause of the Civil War: slavery.