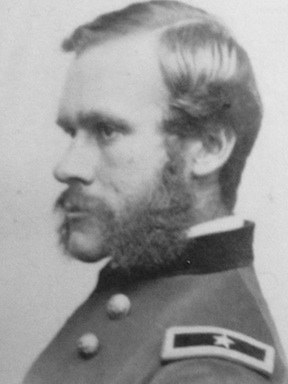

In Memory of Gen. Stevenson

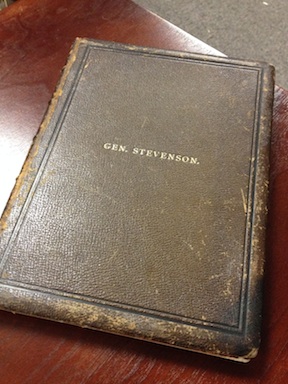

“Thomas Greely Stevenson, the second child and elder son of J. Thomas and Hannah Hooper Stevenson, was born at Boston on the third day of February, A.D. 1836,” reads the memorial book. Gold-edged paper bound in leather, the book serves as the final testament to the brigadier general, killed on this date in 1864 by a sharpshooter’s bullet during the battle of Spotsylvania Court House. A copy of that book sits in my living room.

“Thomas Greely Stevenson, the second child and elder son of J. Thomas and Hannah Hooper Stevenson, was born at Boston on the third day of February, A.D. 1836,” reads the memorial book. Gold-edged paper bound in leather, the book serves as the final testament to the brigadier general, killed on this date in 1864 by a sharpshooter’s bullet during the battle of Spotsylvania Court House. A copy of that book sits in my living room.

Most of the May 10 action centered around Emory Upton’s assault against the western face of the Confederate Mule Shoe. Farther west, the Federal V Corps made assaults against the Confederates posted along a strong position atop the crest of Spindle Field. On the eastern end of the battlefield, where the Federal IX Corps had just deployed the day before, things were relatively quiet, although sharpshooters from both sides harassed officers and soldiers alike.

Stevenson, recently promoted to command of the IX Corps’ First Division, took a bullet at around 8:30 a.m. “a rifle ball piercing his head, while he was surrounded by his staff, cheerful and confident up to the moment he was struck,” says the memorial book.

“Of all losses of gallant men, whom Massachusetts has been called upon to mourn in this war, no one has caused a greater or more general sorrow than that of General Thomas G. Stevenson,” said The Boston Post. “No one will be more universally missed than he.”

Stevenson and his brother, Robert, joined the army in 1861, and he was soon elected to the captancy of his original unit, the 4th Massachusetts Infantry, and eventually became colonel of the 24th Massachusetts. He saw action along the Carolina Coast and took part in the Gouldsboro Expedition. In December of 1862, he earned his stars. He took place in the siege of Charleston through January of 1864, and then he was reassigned to command of the IX Corps division he led first into the Wilderness and then to Spotsylvania.

“No more officer was devoted to his duty,” wrote Massachusetts Governor John Andrew on hearing of Stevenson’s death. “No officer more fully won the respect and love of his men, whom it may be most truly declared that he always led rather than commanded.”

The memorial book, written in the sentimental prose of grieving but proud parents, paints a portrait even more glowing. “He was peculiarly fit for a leader,” the memorial book says:

True manliness was his marked characteristic. Generous, truthful, liberal in his judgments of others, forgetful of self, genial in disposition, and frank in his intercourse with everyone one, he made many friends; and his easy familiarity never detracted from the respect which the true dignity of his character inspired. He shrank instinctively from all unnecessary display. Modest almost to bashfulness, he was nevertheless very determined in the support of any opinions he had formed, and in the execution of any work which he had undertaken.

The memorial book itself is an interesting artifact. Printed in Cambridge, Mass, by Welch, Bigelow, and Co. as a private memorial keepsake it contains letters compiled by Stevenson’s father, Joshua Thomas Stevenson. His signature appears in the frontspiece of the copy my family owns. The person to whom the inscription is addressed, “Jas. H. Blake, Jr.” may have been Lt. James H. Blake, Junior, of the 44th Mass Infantry, Co. I, who was from Boston.

The memorial book itself is an interesting artifact. Printed in Cambridge, Mass, by Welch, Bigelow, and Co. as a private memorial keepsake it contains letters compiled by Stevenson’s father, Joshua Thomas Stevenson. His signature appears in the frontspiece of the copy my family owns. The person to whom the inscription is addressed, “Jas. H. Blake, Jr.” may have been Lt. James H. Blake, Junior, of the 44th Mass Infantry, Co. I, who was from Boston.

“Compiled by Stevenson’s father,” says the Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America, “this privately printed memorial volume includes a short biographical sketch, primarily related to the general’s duties as commander of the 24th Massachusetts Infantry in North and South Carolina, 1862-1863, excerpts from a his letters to his mother, letters of condolences from friends and associates of Stevenson and his family, and obituary notices. Stevenson (1836-1864) and his regiment took part in the campaigns in eastern North Carolina in 1862 and around Charleston in 1863; commanding a division in Grant’s spring campaign against Richmond in May, 1864, he was killed by a Confederate sharpshooter.”

One would expect, then, that the book paint a glowing portrait of Stevenson. But consider the words of a soldier in Stevenson’s old unit, the 24th Massachusetts: “I never knew one so conscientious in the performance of his duty, or truer in his friendship that General Stevenson.” He was, the soldier said, “loved by all his old companions in the regiment with particular affection.”

“He was a noble fellow and well deserved the praises that have been lavished upon him,” wrote another.

Stevenson’s commander, Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside, worn by the constant pressure of the unrelenting Overland Campaign, was unable to write to Stevenson’s parents about their son until June 2. Burnside commented on Stevenson’s short time with the IX Corps—”a time memorable for its fatiguing marches and its constant succession of desperate engagements.”

“[H]is course was invariably marked by the most cheerful and untiring devotion to his duties and the most conspicuous gallantry,” Burnside wrote; “and his death was deplored by the many new friends, who had in that time of trial learned to respect him, as well as by those older friends, to whom his worth had long been known.”

As a short-tenured division commander in the most underperforming Federal Corps, along the least-known front of the battle, it’s little wonder that Stevenson is barely remembered today or that his death gets little mention. Even Stevenson Ridge, named after the fallen general, serves as an imperfect memorial: Stevenson was killed not on the property itself but, near as we can tell, on a parcel not too far away.

I’m glad, at least, to take a moment to remember him—perhaps not as he was but as his parents wanted me to remember him.

Do you have an address for Thomas G Stevenson in Boston? We have this book, and I believe the address is in it, but I didn’t look it up before we left. We will be visiting Boston Friday and would like to try and find Gen. Stevenson’s home.

Unfortunately, I don’t. Good luck tracking him down!

I just stumbled on this post today. I also have a copy of this rare book published by the father of General Stevenson. My copy is inscribed to General Joseph Warren Revere, grandson of the patriot, commander of the 7th New Jersey, and brigade commander. At Chancellorsville, Revere marched his brigade to the rear during the thick of the fighting on May 3rd and was court-martialed. President Lincoln apparently over-turned the conviction and Revere was allowed to gracefully resign from the Army. He died in 1880 at the age of 67.

Chris — where did you find your copy?

I’ve recently become fascinated by Stevenson. Emory Upton gets all the press, but this quiet performer deserves more!