Empty Arms: A New Sesquicentennial Image

Today, we are pleased to welcome back guest author Sarah Kay Bierle

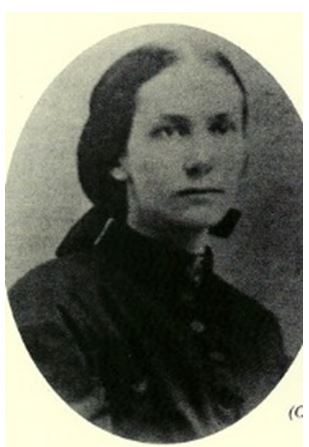

Kate Corbin Pendleton’s photo is framed on my work desk. Her solemn expression and sad eyes have haunted me as I’ve read articles of delight, debate, and dissention as the Civil War Sesquicentennial comes to a close. The dead, the wounded, and the veterans have been remembered, and yet some of the living have been forgotten. There is an echo – a faint whisper – that has been missed in most of the memorializing of the war. Young Mrs. Pendleton wrote in 1865: “…I wonder people’s hearts don’t break… My poor empty arms…Oh! Pa, unless you lose your only one you don’t know how sharp the pang is and no words of mine can tell the agony of my struggle…”[i]

Families on both sides lost loved ones and friends during the war. However, for the ladies of the South, the post war world was especially bleak. The war directly and indirectly affected ladies’ role in society. Traditionally sheltered and esteemed, many of these ladies found themselves without protectors and with few options for the future.

During the conflict – as the men who were the leaders, protectors, and providers in traditional Southern society – left home to join the armies, ladies were forced to adopt new roles in agricultural or business management, often performing the heavy work in the households and farms. Invasion of the Confederacy by Union troops brought occupations and battles to the doorstep of the homes. Fearing insult, injury, and theft, some women chose to flee and became refugees; others rebelled in obnoxious yet feminine ways against the demands of Yankee soldiers and officers. Ever increasing food shortages and improvisation were almost universal on the Southern home front. Adding to the war difficulties was the emotional strain. Long casualty lists broke thousands of hearts. Some girls married and were widowed within a month.

And yet, there was still determination and a faint hope for victory until the war ended. It seemed that if the South won, there could be a sort of justification for the suffering, loss, and deaths. The surrenders of the Confederate forces ended all reasonable hopes…and, suddenly, Southern ladies found themselves facing a stark reality. “Oh, my brothers! What have we lived for except you? …What will life be without the boys? When this terrible strife is over, and so many thousands return to their homes, what will peace bring us of all we hoped?”[ii]

With many men gone forever or physically or mentally injured, the women attempted to put their lives and society back together and move forward. In many ways, Southern ladies had been the gatekeepers of their culture; they raised the children, extended hospitality, and stabilized the societal bedrock on which the men oversaw the economy and debated the politics. Thus, the ladies’ efforts to start rebuilding society after the war are significant.

Though many aspects of their pre-war society were gone, the ladies clung to the traditional roles of women, controlling the domestic sphere and not intruding into the man’s world. Most Southern ladies did not enter the early feminist movement, but rather returned or remained at home, seeking to repair the damages to property, lives, and loved ones. However, to some extent the war destroyed social classes, and women found their antebellum society with its rigid class structures had disappeared and they tried to adapt to the new social settings. There were many women who did not have homes and had lost all male protectors and providers. These ladies entered the work force, but preferred jobs as teachers or seamstresses, which reflected a traditional domestic role. They rebuilt their lives and cared for their surviving family members.

One hundred and fifty years ago, Southern ladies were standing in front of burnt homes, embracing a limbless husband, or scraping together food to feed their hungry children. Many others looked at a precious photograph, wondering if their beloved was dead, alive, or what his grave looked like. Others, like Kate Pendleton[iii], wandered to the graveyard to sit by “his quiet bed.”[iv]

Katherine Corbin Pendleton experienced the destruction of her family home, the death of her brother, the wartime shortages, and yet she expected a happier ending. On December 29, 1863 – after a lengthy engagement – she had married Alexander S. Pendleton, a young and respected staff officer of the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. Clearly happy in her married life, Kate wrote about her husband, “We harmonized so perfectly in all our tastes and aspirations; he was so thoughtful of my slightest wishes, so good & true & my soul was so bound up in him.”[v] Kate’s blissful plans seemed almost complete when she discovered she was expecting a baby.

However, like so many other ladies throughout the South, Kate’s ideals faded to distant dreams. Colonel Pendleton was mortally wounded during the Battle of Fischer’s Hill (September 22, 1864) and died the following day. Friends brought the news to Kate and the Pendleton Family in Lexington, Virginia. The funeral was delayed by the military campaigns, and just weeks after her husband’s burial, Kate gave birth to a healthy baby boy. The baby brought comfort to the family, but, sadly, he died of a childhood illness before his first birthday. Kate wrote a letter to her father, calmly telling of her son’s last days, and finally breaking down with the realization of her empty arms. She had lost her son and her husband in less than a year.

Yet, like many other widows across the South, she turned to her faith, trusting God would see her through this difficult time. “All my work in life now is to try to live so as to meet them in Heaven…. If God loves all he chastens, surely I have good reason to believe he loves me. I trust so indeed.”[vi] Her strong faith, determination, and feminine courage helped her survive the tragic loss. Kate remained in Lexington with the Pendleton Family, became a governess at a local school, and remarried in 1871.

Generally, the Southern ladies were not physically wounded by the war, but they were its living victims; life would never be the same because of the conflict. Considering the focus of reunion in the 1865 Sesquicentennial, it is easy to understand why it is preferable to slide away the images of the homes touched by war. Those accounts drive deep into our hearts. They become the whisper in our ear when we read about battles: remember who was waiting for him at home.

Viewing the historic photos of the dead at Antietam, Gettysburg, or Petersburg leaves any thoughtful person reflecting on the cost of war. We may even turn away from a particularly gruesome photo, praying for the end of wars. To many, it would seem much less moving and traumatic to see a lady’s photo, but look at her eyes. Only the living know heartbreak. The dead do not know earthly emotion, only the living.

As I think about the ending of the Civil War, a hundred images flash through my mind. Triumphs, hospitals, lonely veterans, homecomings, memorials, long roads home… And then the faint, whispered words from the text of almost forgotten manuscripts conjures new images. An image of a black skirt trailing along a dirt road. A hand on the iron gate of a graveyard. Flowers on a grave. Tears on a young face that should only have smiled in joy. This is one of the war’s silent victims.

“I can’t tell you how much I miss him and long for him, nor how I try not to repine at God’s Providence.”[vii] She lost everything except her faith and her courage. And yet she rose and walked away from that solemn grave and strode forward. Though frightened, she learned to care for herself. Though heartbroken, she tried to heal a nation. Though her arms were empty – never again to embrace her husband or hold her son close – she still met every difficulty with the gracious determination which had always been a key characteristic of a Southern lady.

[i] W.G. Bean, Stonewall’s Man: Sandie Pendleton, (1959), 231.

[ii] W. Sword, Southern Invincibility: A History of the Confederate Heart, (1999), 199, 200. Note: This except is from Sarah Morgan’s diary; the entry is from 1863, but the sentiment echoes with finality and is closely related to 1865 accounts.

[iii] Note: Kate’s full name is usually listed as Catherine Carter Corbin Pendleton Brooke; she was a member of the Virginian families Carter and Corbin, she married A.S. Pendleton, and six years after her husband’s death married J.M. Brooke. Since this article’s goal is not Kate’s genealogy, I have elected to call her Kate Corbin Pendleton, the names by which she would have been known during the Civil War era. The first name on her grave is “Kate”, not Catherine, so I have decided to continue with the preferred name.

[iv] W.G. Bean, Stonewall’s Man: Sandie Pendleton, (1959), 231.

[v] W.G. Bean, Stonewall’s Man: Sandie Pendleton, (1959), 183.

[vi] W.G. Bean, Stonewall’s Man: Sandie Pendleton, (1959), 231.

[vii] W.G. Bean, Stonewall’s Man: Sandie Pendleton, (1959), 225.

To Sarah Kay Bierle: I found this to be easily one of the most affecting posts on this site. Thank you.

Agree completely. and have long desired a balanced view of the South as a country and a culture as well as the suffering following the conflicts. This really addresses all of that. The industrial and agri regions of the young nation were drawn up and underlined by our founding fathers, including the North as traders and transporters of human flesh and the South as the farmers with slave labor that could only provide the food for a nation with that immoral labor. A gentlemen’s agreement? Thank you for the balanced portrait of a huge part of our historical landscape. Many of us feel certain political anomalies in recent years could never have happened if the final days of the War and it’s aftermath had been treated as carefully and diplomatically as Lincoln had wished. He died and of course it’s all history now.

So well done, Sarah! There is a wonderful book–Weirding the War–that talks about the issues of southern women who were asked to choose the “empty sleeve” over a man that had not served. Very touching.

Thank you all for your kind comments. This was a tough article to write, but I’m thankful I was able to share it. I appreciate the book recommendation, Meg, and will certainly look for it.