On Meade’s Mind, 152 Years Ago

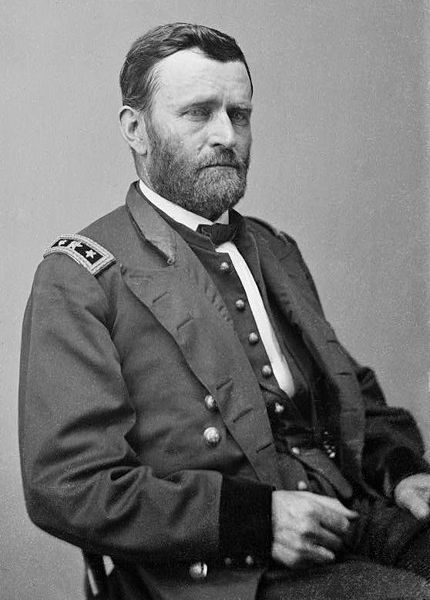

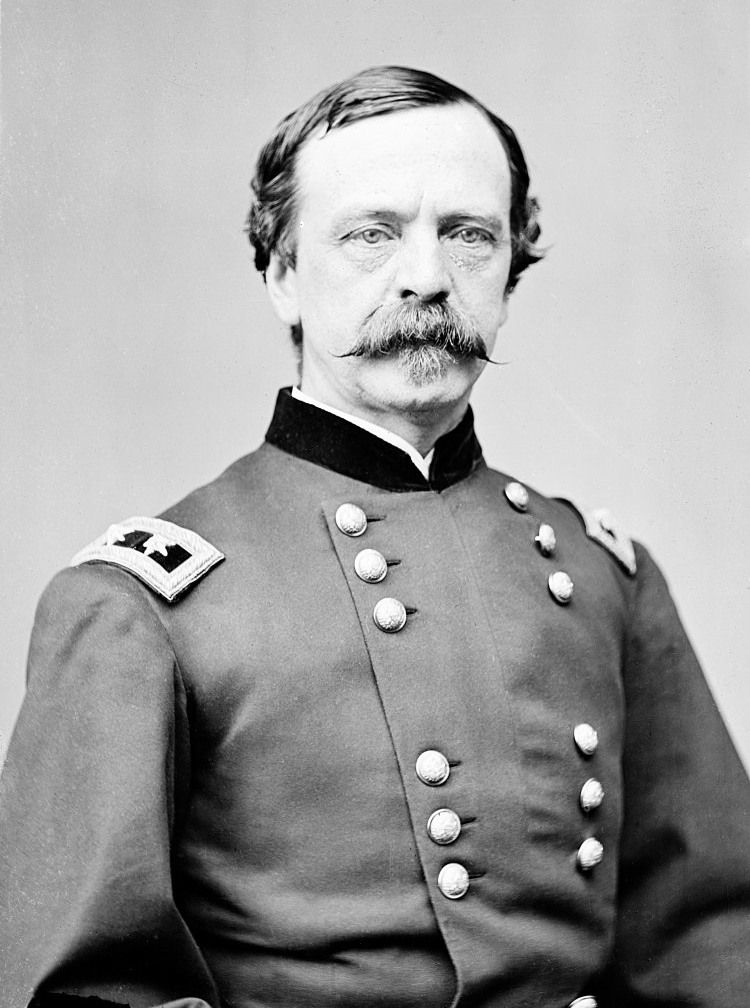

George Gordon Meade had much on his mind as he waited for the train from Washington to arrive. Onboard, the general-in-chief of all Union armies, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, was coming from Washington to take his place with the Army of the Potomac.

“Grant is emphatically an executive man, whose only place is in the field,” Meade had confided to his wife in a letter two days before. “One object in coming here is to avoid Washington and its entourage. I intend to give him heartiest co-operation, and so far as I am able do just the same when he is present that I would do were he absent.”

The date was March 24, 1864—152 years ago today.

The train, traveling southwest on the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, stopped at Brandy Station—“the depot near my headquarters,” Meade called it—where Meade met his new boss. The two generals traveled together into Culpeper, where Grant had set up headquarters, and spent several hours talking. “He was as affable as ever, and seems not at all disposed to interfere with my army in any details,” Meade reported to his wife that night.

Had Grant not come to the army once already, on March 10, Meade might have had more to worry about that he already did. On that visit—Grant’s first to see Meade since assuming overall command of all Union armies—the specter of dismissal hung over Meade like a shroud, and Meade even offered his resignation if Grant saw fit to accept it. That act, Grant later admitted, impressed him moreso even than Meade’s victory at Gettysburg. Meade, too, came away from the meeting impressed. “He has been very civil, and said nothing about superseding me,” he told his wife.

With that elephant hunted out of the room, Meade had little concern about Grant’s return two weeks later. “[F]rom all I can hear of what he has said of me to others, I ought to be satisfied,” Meade wrote in advance of the meeting, “as I understand he expressed every confidence in me, and said no change would be made in the command, as far as he was concerned.”

Yet change was nonetheless on the wind, even if Meade stood as the calm eye at the center of the storm.

Most immediate was a major reshuffle of the army. “The much-talked-of order for reorganizing the Army of the Potomac has at last appeared,” he wrote to his wife on the night of March 24. “Tardy George” Sykes was out as Fifth Corps commander; William H. “Blinky” French was out as Third Corps commander; John Newton was out as First Corps commander. Cavalry commander Alfred Pleasanton was relieved, too.

Sykes’s loss he regretted most, although he tried to retain him, Newton “and even French” at least as division commanders, but to no avail. Meade found he even had “very hard work to retain Sedgwick” as Sixth Corps commander, he revealed days later. He showed ambivalence about Pleasanton.

The reorganization and resultant shake up meant things in his immediate surroundings suddenly jumped into flux—and that didn’t even take into account the presence of the general-in-chief. But matters back in Washington also gnawed at him.

“I hear Butterfield is in Washington. . . .” he wrote his wife on the night of the 24th. Butterfield was supposed to be stationed with the Twentieth Corps in northwest Georgia, even then preparing under William T. Sherman to launch its spring campaign, yet he had snuck his way to Washington against the wishes of superiors so that he could testify before the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War.

On July 2, 1863, after destroying his own Third Corps of the army by moving it out of position against orders, Dan Sickles had his leg blown off. Taken to recuperate in Washington, he launched into a war of words against Meade in an attempt to cover his own major bungle. Anyone with an ax to grind against Meade joined in, including Butterfield, who had served as Meade’s chief of staff during the battle. Sickles conspiratorially beckoned Butterfield to come from Georgia to testify even though Sickles had no authority to summon him and Butterfield had no permission to go.

Disgruntled Abner Doubleday joined in, too—disgruntled because he’d been replaced as head of the First Corps by, ironically, the just-reassigned John Newton.

“It is a melancholy state of affairs, however, when persons like Sickles and Doubleday can, by distorting and twisting facts, and giving false coloring, induce the press and public for a time, and almost immediately, to take away the character of a man who up to that time had stood high in their estimation,” Meade lamented in a March 6 letter.

The Joint Committee’s witchhunt weighed heavily on Meade, who had resigned himself to “be patient,” convinced the truth would “slowly and surely make itself known.” “It is hard that I am to suffer from the malice of such men as Sickles and Butterfield,” he lamented.

A new commander, a reorganized army, an ongoing witchhunt—these things all weighed on George Gordon Meade 152 years ago today. As he told his wife in his day’s-end letter, “I have had a very busy day to-day.”

* * *

Excerpts from Meade’s letters come from The Life and Letters of George Gordon Meade, Vol. 2, pp. 170, 177, 182-183, 185.

Chris:

Excellent, excellent post.

The mostly smooth relationship between Meade and Grant was a major reason for the Army of the Potomac’s success during the last 13 months of the war.

Thanks so much, Bob. I agree, the relationship between the two went a long way toward Union victory. I know Meade pined a bit under Grant’s thumb, but he was always too much of a professional to let it affect his performance. Grant, never one to make a fuss about such things, really liked Meade.

IMHO there would be many successors to the unwarrented attacks on Mesde, including Winston Churchill and George W. Bush.