Herdegen’s Rock-Solid Study of the Iron Brigade

I first met the Iron Brigade, like so many Americans, as they marched onto the field on the first day of Gettysburg, their black hats announcing their appearance at the nick of time. Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels (and the subsequent film Gettysburg) makes much of the Iron Brigade’s timely appearance, in part to add dramatic weight to the death of John Reynolds a few pages later.

I first met the Iron Brigade, like so many Americans, as they marched onto the field on the first day of Gettysburg, their black hats announcing their appearance at the nick of time. Michael Shaara’s The Killer Angels (and the subsequent film Gettysburg) makes much of the Iron Brigade’s timely appearance, in part to add dramatic weight to the death of John Reynolds a few pages later.

I later met the Iron Brigade in the Wilderness as they ran pell-mell through the forest—“like scared little girls,” one colleague liked to say—after Confederate counterattacks in the dark, close wood caught them completely off guard and crushed them.

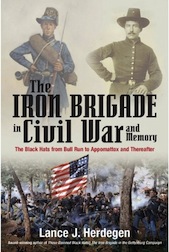

I’ve run into them on many occasions since, but no meeting has been so fortuitous, or so interesting, as meeting them in Lance J. Herdegen’s excellent book The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory: The Black Hats from Bull Run to Appomattox and Thereafter.

“The Iron Brigade may have been the best combat infantry brigade of the American Civil War,” Herdegen says. While many would contest that statement, Herdegen makes a whopping 696-page argument that’s pretty convincing. “At the end of the war,” he points out, “it was determined the Iron Brigade regiments suffered the highest percentage of loss of any brigade in the Union Armies.”

Certainly the Iron Brigade is one of the most storied units in the entire Army of the Potomac, in no small part because so many members of the brigade chronicled their exploits after the war, circulating those adventures to wide acclaim. We “had fought on more fields of battle than the Old Guard of Napoleon, and have stood fire in far greater firmness,” one member of the brigade said.

At the time, the Iron Brigade first earned attention as the only all-Western brigade to serve in the Eastern Theater, comprised as they initially were of the 2nd, 6th, and 7th Wisconsin, the 19th Indiana infantry regiments (with Battery B of the 4th U.S. Artillery through in there, too). Their black felt hats gave them a particular battlefield élan not hard to miss, either.

Herdegen traces the brigade’s history in painstaking detail without bogging down in the weeds. He doesn’t sacrifice readability to achieve thoroughness, either. Herdegen knows how to keep his narrative engaging—no small feat considering the number of sources he works into the story. He draws on decades of research to tell this story.

Gettysburg gets the lion’s share of attention compared to other engagements, but that’s as much because there’s 150 years of muck Herdegen has to sort through as anything else. Certainly the brigade’s actions on May 1, 1863 deserve the focused discussion Herdegen gives them.

What’s more important about the book, however, is the detailed attention Herdegen gives all of the brigade’s exploits. The early section of the book, “Greenhorn Patriots,” may be my favorite because it’s a wonderful snapshot of a group of eager but inexperienced—and sometimes scared—men learning to be soldiers. “All had to learn the business of war,” a chapter header proclaims.

The book’s last section, too, deserves special attention. “Thereafter and Evermore” follows survivors of the brigade softly into that dark goodnight with some poignant observations.

I was glad to again meet these men of the Iron Brigade under such enlightening conditions. Herdegen does great honor to their memory while doing great service to the Civil War community by presenting their story so well. The Iron Brigade in Civil War and Memory is a well-crafted piece of scholarship worthy of the men whose exploits it recounts.

Outstanding review, Chris. Many thanks for taking the time and trouble to review this important title.