The Season of Battles: Perspectives on the 1863 Campaigns

This year marks the 150th Anniversaries of some of the Civil War’s most iconic engagements. The sesquicentennial of Chancellorsville and Stonewall Jackson’s death has just passed, while the Vicksburg and Gettysburg commemorations are in the future, followed by Chickamauga. Yet focusing on any one event over others obscures some of the key historical currents that run through this period of the war.

The 7-month period that started May 1, 1863 saw events and blood-lettings unlike any previous time-frame in American history. At the end of November, the United States had a better feel for how victory (and the resulting new Union) would be defined.

To grasp the forces at play, the best thing to do is start toward the beginning of the campaign season and look forward from that perspective. If we were to pause time on May 11, 1863, what would we find? A brief survey shows numerous global conflicts. China is undergoing its own rebellion, and a little-known general named Charles Gordon is within weeks of rising to fame; Poland is rebelling against Russia; the French are overthrowing Benito Juarez in Mexico; Europe is sliding closer to war as Otto von Bismarck works to unify the German Empire; and the United States continues to fight itself in the largest war between 1815 and 1914.

On May 11, both the Union and the Confederacy are assessing the Union defeat at Chancellorsville in Virginia. This engagement was the bloodiest battle in U.S. history up to that point with over 30,000 casualties of all kinds, losses which ripple across North and South. The mortal wounding of Stonewall Jackson has thrown the Confederacy into deep mourning. Chancellorsville has also infused the victorious Confederate commander, General Robert E. Lee, with a belief in the invincibility of his troops.

In Mississippi, on May 11 U.S. Major General U.S. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee is setting out for Jackson, aiming to cut Vicksburg off from the rest of the Confederacy and either take the city by storm or starve the garrison into submission. Vicksburg is the strongest Confederate outpost yet held along the Mississippi River; if it falls, the Confederacy effectively will be cut in two.

Neither side yet knows it, but the events of this summer and fall of 1863 will have a profound impact on the war and the nation. Here’s three of the major themes that emerge from this period:

UNION VICTORIES: The Confederacy receives a body blow in early July from which it will never fully recover. The four Union victories consummated during this period (Gettysburg on July 3, Vicksburg and Tullahoma on July 4, and Port Hudson on July 9) place the Confederates on the strategic defensive for the rest of the war. Confederate efforts to stem to blue tide ultimately fail in and around Chattanooga in the fall. It is too much to say the South was doomed after this (they have a real chance to win in 1864 by ruining Lincoln’s reelection), but the Union assumes an ascendant strategic posture from this point forward.

DEATH AND DEFINITION: Within 100 days, the three bloodiest battles of the Civil War (Chancellorsville, April 27-May 6, 1863; Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863; and Chickamauga, September 18-20, 1863) all occur. Cumulatively, they total 118,000 casualties, a concentrated bloodletting unequaled in U.S. military history until the 20th Century. The casualty lists lengthen at smaller battles like Brandy Station, Port Hudson, Tullahoma, Knoxville, and Chattanooga. Add in the 29,000 Confederates surrendered to Grant at Vicksburg, a larger number than he took at Appomattox, and the number grows further.

This vast human destruction burns the four largest battles of this period (Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Chickamauga) into the national psyche forever. The latter three of them are among the first battlefields preserved and the most extensively monumented by veterans. All four are among the most visited battlefield parks today. The bloodletting also inspired a national search for meaning, which is answered in Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address in November 1863.

RISE OF UNION LEADERSHIP: In addition to being a national turning point, this period brings forward the U.S. leaders who are destined to play important roles in crushing the Confederacy. Some of them have been prominent in lesser positions, but now are stepping into senior roles for the first time. Several of these new stars will be key leaders for the U.S. Army throughout the rest of the 19th Century. A partial list of those who rise in the summer and fall of 1863 includes: U.S. Grant, William T. Sherman, Winfield S. Hancock, James B. McPherson, George G. Meade, Edward O.C. Ord, Henry W. Slocum, George H. Thomas, Jefferson C. Davis, Oliver O. Howard, John M. Schofield, John G. Parke, Philip H. Sheridan, Wesley Merritt, Andrew A. Humphreys, Gouverneur K. Warren, and George A. Custer.

As the nation commemorates the events of the summer and fall of 1863, we should remember these three themes, for they set a stage for the rest of the war and beyond.

Very nice article. Good to see you writing for ECW. It has been some time since we spoke.

Give me a buzz and let me know how things are in Ky. Regards from the Phil Kearny.

Joe

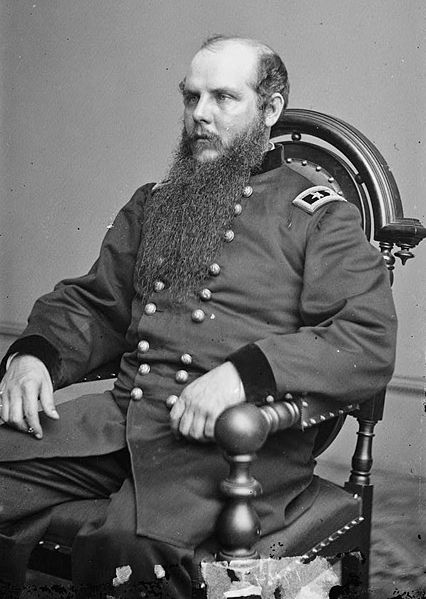

Loved the article, but hated the photo of General John Schofield. He was just a Halleck snitch.

Reblogged this on Poore Boys In Gray and commented:

Good summary of the meaning of the 1863 campaigns. My question always is,”If you were a rebel, when did you realize the cause was lost? And what would you do?”

Good summary of the meaning of the 1863 campaigns. My question always is,”If you were a rebel, when did you realize the cause was lost? And what would you do?”