“The Weather Was Intensely Hot”: Cold Harbor After the Fighting

After the Union attacks had subsided on June 3, 1864, the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac stared at each other across the open space that separated them. Men in each army strove to improve their position as best they could. For many, this meant digging at the red soil and building earthworks. Soldiers recalled that each side was especially tense. A single shot from a lone picket would bring down a barrage of artillery fire on that specific sector. Occasional sniping between the Yankees and the Rebels occurred up and down the lines.

A Mississippian, who had recently survived the fighting at Spotsylvania’s Bloody Angle wrote “all around lay the shallow graves of those who had fallen in the former Battle of Cold Harbor…at night these old graves would shine with a phosphorescent light most spooky and weird, while on the surface of the ground, above the ghastly glimmering dead, lay thousands of dead that could not be buried…at night we buried our dead who had fallen in the trenches, as did the Yanks, but neither side could get at those who fell between the lines. We became indifferent to the noise and bloodshed and privation of the horrible scenes, but we could not be indifferent to the stench arising from the unburied dead”.

John Gibbon, commanding a division in Winfield Scott Hancock’s II Corps remembered “the weather was intensely hot…the fine sandy soil turned to dust. On some parts of the line, particularly on my right, not water was to be had, and none was obtained until darkness enabled the men to crawl back and supply themselves and their comrades from a stream near by, to connect with which a trench was dug and an embankment thrown up during the night and by this means communication was established with the rear. In the meantime our killed and wounded lay out in the space between the lines, those of the latter who could not crawl suffering intensely. Every effort was made during the night to get to them the water and to bring them in, but these efforts resulted in the enemy opening fire”.

The cries of the wounded were not just heard by a Confederate private or a Yankee division commander. Winfield Scott Hancock also heard the cries and appealed to his friend George Meade as to whether something could be done to assist the wounded. Meade referred the matter to Grant who penned a note to Robert E. Lee:

“It is reported to me that there are wounded men, probably of both armies, now lying exposed and suffering between the lines occupied by the armies…I would propose…when no battle is raging, either party be authorized to send to any point…unarmed men bearing litters to pick up their dead and wounded”.

The chess game being played between Grant and Lee on the battlefield over the last month now moved to their dispatches. Lee responded by suggesting that the Federals send out a flag of truce, as required by military protocol. As governed by the rules and articles of war, such a gesture would be an admission of defeat on the part of Grant. This was something that Grant was unwilling to do outright. He had pushed Lee back from the Rapidan to the threshold of Richmond at the cost of thousands of men killed and wounded and he was not about to concede a loss to his opponent.

Grant may have also considered the ripple effect of sending out a flag of truce. Later that year, residents of the Northern States would be going to the polls to elect the next President. A defeat in one of the major theaters of war could potentially have catastrophic results for Abraham Lincoln who was running on a platform of seeing the conflict through to the end.

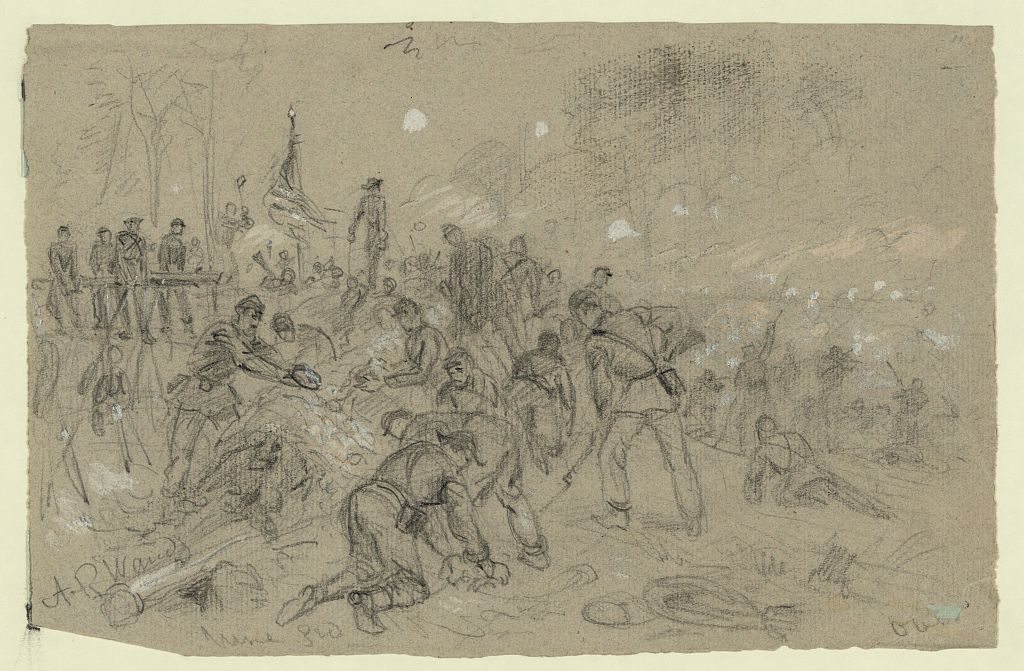

Instead, Grant proposed a “suspension of hostilities” to which Lee agreed. On June 7, Union stretcher bearers made their way out from the lines. Gibbon would lament “it was not until four days afterwards…that we were enabled…to collect our wounded and bury the dead. The latter had by that time become a mass of corruption very offensive to everybody, friends and enemies, in the vicinity. I saw one poor fellow brought on a litter into our lines with a broken thigh. He had subsisted on three days on the spears of grass which he could reach with his hand from the point where he lay and smiled cheerfully when I spoke to him at the thought that, at last, he was where he could get food, drink and attendance”.

The truce negotiations were not the only thing occupying Grant’s mind in the days following the June 3 assault. This attack had proven that Lee’s lines was impenetrable. Now, he would have to find a way to get around.

I am very intrigued about graves shining with a phosphorescent light. Does anyone have any explanation or know of other references to this? Did any other soldiers report the phenomenon at Cold Harbor? What does it mean?