“A Hideous Dream”: The Federal Second Corps at the Second Battle of Ream’s Station

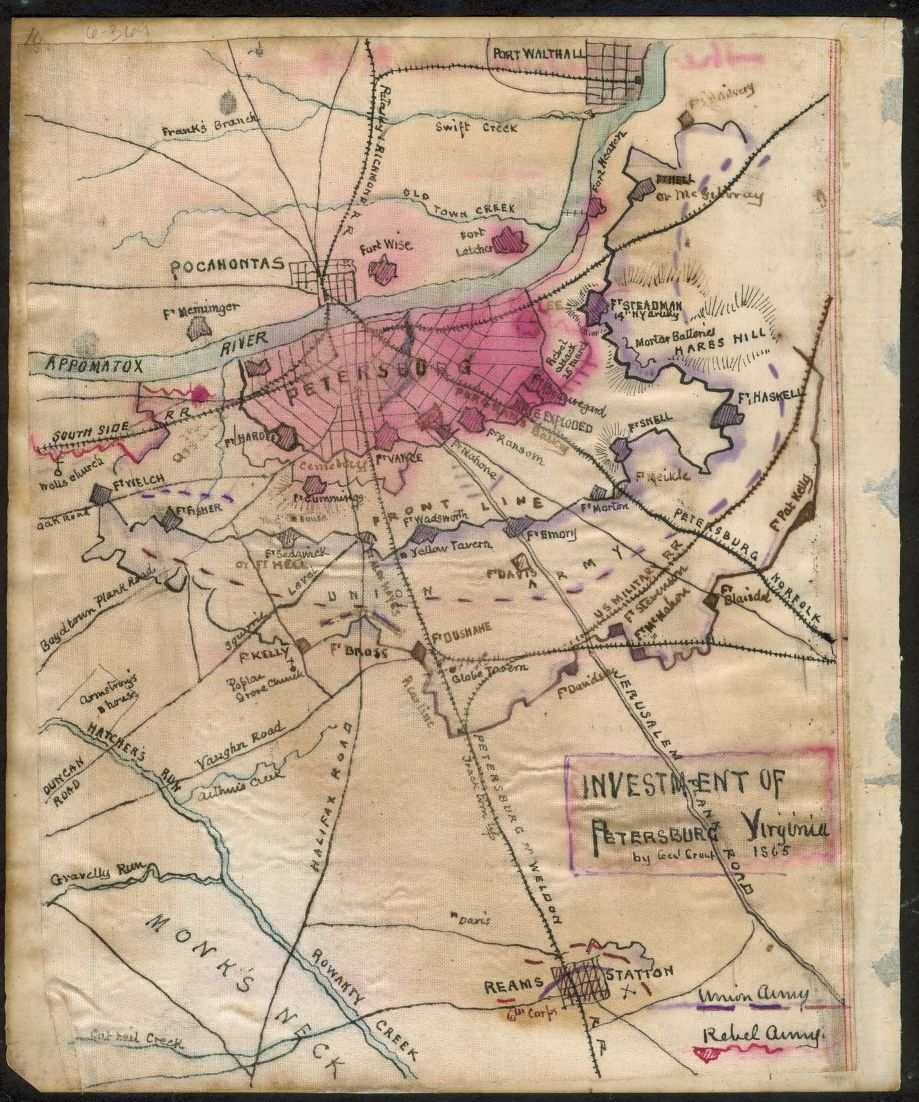

In the wake of the fighting around Globe Tavern, the Federal high command looked to expand on its success. The Weldon Railroad was firmly under the control of Warren’s Fifth Corps, but now George Meade wanted to negate the railroad entirely. To do so, Meade ordered Winfield Scott Hancock’s Second Corps up.

Throughout early August Hancock’s men had been involved north of the James River, fighting in the engagement known as Second Deep Bottom. Only on the night of August 20-21 had the corps re-crossed the river and now, with little rest, was ordered twelve miles south of Petersburg towards Ream’s Station. As the tired men began the march, some of them quipped that they were now “Hancock’s Cavalry.”[i]

On August 22 the first of Hancock’s men arrived at Ream’s Station. The first arrivals were in the First Division, normally under the leadership of hard-hitting Francis Barlow. But Barlow had left the division a few days prior; his wife had died in late July and the strenuous campaign had played havoc on his health. Departing on a well-deserved leave of absence, Barlow left his division under the command of Brig. Gen. Nelson Miles.[ii]

(Library of Congress)

Miles was a well-experienced combat veteran and his men relieved the cavalry pickets at Ream’s Station under David McM. Gregg. From that point, the Federal infantry began tearing up the tracks of the railroad. By August 24, the division had torn up the line three miles south of the station. That same afternoon, John Gibbon’s Second Division arrived and joined Miles in the destruction.[iii]

In the middle of the night of August 24, Hancock received a message from Army Headquarters. Meade wrote in warning, “Signal officers report large bodies of infantry passing south from their intrenchments… They are probably destined to operate against General Warren or yourself… The commanding general cautions you to look out for them.”[iv]

(Library of Congress)

Hancock was left in a desperate position. His two divisions had been constantly engaged since the Army of the Potomac had crossed the Rapidan before the Wilderness. It had done the brunt of the fighting on May 12, at the Bloody Angle; during the chaos at Cold Harbor, Hancock’s men had achieved the only Federal success; and on and on. Across the James River, the initial assaults at Petersburg, Jerusalem Plank Road, and Deep Bottom had all led to a shattered corps. From 20,000 men at the start of the campaign, Hancock could rely on about 6,500 for the upcoming fight at Ream’s Station.[v] Most of his regiments had been inundated with replacements with hardly any combat experience. Now those two divisions faced an imminent assault from A.P. Hill’s Confederates.

Thursday, August 25, 1864 found Hancock exchanging his divisions’ roles. Hancock had waited for any rebel movements until around 8 AM, but then, finding none, lulled into a false sense of security. The fatigued men of Miles’ division took watch over the corps while Gibbon’s newly arrived troops took up the work of tearing up the tracks. Up ahead of the lines Gregg’s cavalry continued to act as vedettes.[vi]

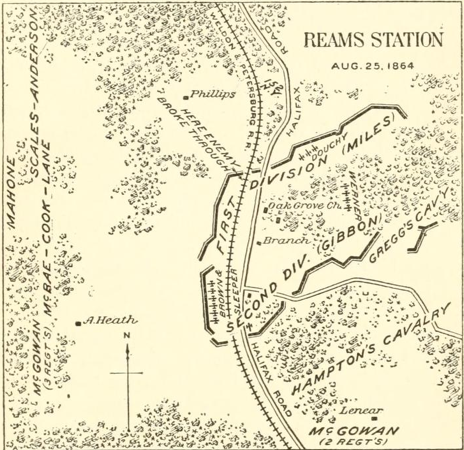

The Battle of Second Ream’s Station began early that morning as Wade Hampton’s cavalry, leading the Confederate advance, ran into Gregg’s men. Quickly falling back in front of Hampton, the Union troopers alerted Hancock. Gibbon’s men were ordered to pick up their rifles and join Miles.[vii]

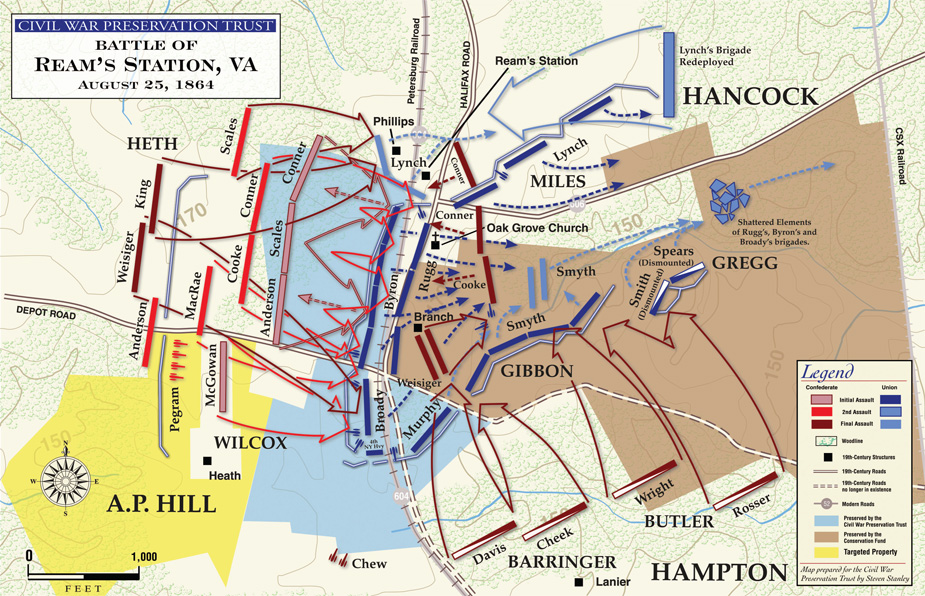

Problems began to arise for the Federal infantry almost as soon as the first shots were fired. Chief among their problems was the status of their defensive positions; in a changing world of combat, earthworks had become the standard for both armies in the summer of 1864. And in a word, the Federal lines at Ream’s Station were horrible.

Hancock’s men had not dug the works around the station—they were left over from the First Battle of Ream’s Station in June. As part of a cavalry engagement known as the Wilson-Kautz Raid, the Union troopers had had the assistance of the Sixth Corps, which had turned out to protect their cavalry’s return. The Sixth Corps had dug the works hastily, not intending to stay in them. As the raid finished, the Federal infantry left their works, and a month and a half later the Second Corps now had to rely on those same, lackadaisical positions. One of Miles’ men commented that, “They [the works] had settled down and was too low [to protect the troops]. They was very poor works.”[viii]

Francis Walker, one of Hancock’s staffers, described the earthworks with disgust: “It will be seen that only a short face was presented to the enemy, and that both sides of the works, as drawn back… were exposed to an enfilading fire. Moreover, the distance across, from one side to the other, was so short that the enemy’s artillery on either side could make the opposite line untenable… But the worst feature was that the front of the works extended beyond the railroad. The two batteries and the few small battalions which were to receive here the assault of Lee’s veterans… found themselves with a low parapet in front, while behind them, at a distance perhaps of twenty or thirty yards… ran the railroad, forming here an embankment… which made it impossible for ammunition or reserves to be brought up, except at disadvantage…”[ix]

Basically put, the Federal lines formed a U that had fallen over onto its side. Miles’ division covered the left and front of the U while Gibbon’s men faced towards the right and rear. Miles and Gibbon both had their men in works that extended beyond the railroad’s high embankment; artillery batteries that had been placed in support were posted with little cover because of the railroad. One can imagine the disgust of the troops as, after all, this was the same corps that had used a railroad bed to great use at the Battle of Bristoe Station in October, 1863. Now the tracks and embankment would be against them.

The first Confederate troops hit Miles’ front around noontime. Driving in the Federal skirmishers, the rebels, under the direction of Cadmus Wilcox were soon turned back. Miles sent his skirmishers forward again, and an hour later, at 1 PM, Wilcox was again repulsed “under a severe fire of musketry.”[x]

By 3:30 PM, Wilcox’s men had attacked and been repulsed twice. Miles’ front was holding, and Gibbon’s troops were providing support on the left flank. Nothing pointed to the fact that Ream’s Station would turn into the worst day of the Federal Second Corps. For the time being, the firing slackened.[xi]

While the Federal soldiers waited in their lines, the Confederates were planning their next move. The rebel high command had had problems of their own; A.P. Hill’s sickness had once again flared up, forcing him to turn over command—first to Cadmus Wilcox and then to Henry Heth. Heth took control of the situation as he brought up some of his own brigades to add to the mix, as well as a variety of artillery under the capable command of William Pegram. Pegram soon began positioning anywhere from 12-17 guns in order to open fire.[xii]

As Heth brought up fresh infantry, and Pegram placed his guns, Hancock’s own forces were having new problems. With their artillery batteries exposed, Union gunners and horses soon began falling prey to Confederate sharpshooters. With no where to take shelter behind the low works, and the railroad embankment hemming them in front behind, the Federals continued sustaining casualties.[xiii]In the face of the sharpshooting, Federal Heavy Artillery units, which had been acting as infantry, took up the places of fallen gunners.[xiv]

Finally, around 5 PM, having taken close to two hours to prepare, Heth was ready to strike. Pegram’s guns opened fire, shelling the Federal lines for close to forty minutes. The fire proved especially destructive because of the faulty design of the earthworks; Pegram targeted Miles’ front but even shots that fell behind Miles landed amongst Gibbon’s ranks. In his memoirs, Henry Heth later wrote, [T]o Colonel Pegram I measurably owed my success at Ream’s Station…”[xv]

Around 5:40, Heth unleashed his last infantry assault. The day’s fighting and the strenuous artillery barrage had softened the Federal infantry’s resolve. Striking the Union lines, Heth’s men acted like a nutcracker; the Federal line split open at the seams. Confederate soldiers vaulted over the works and sent the Union infantry reeling while, from the left, Wade Hampton unleashed an assault of his own.

(Reprinted from the Civil War Trust)

Riding into the confusion of his retreating men, Hancock tried to rally his men. He pleaded with them, “Come on! We can beat them yet! Men, will you leave me?”[xvi] His horse was killed and Hancock said to a staffer, “Colonel, I do not care to die, but I pray to God I may never leave this field.”[xvii]

Nelson Miles was also trying to rally his troops and retake the lost works. To do so, Miles looked to the regiment he had served with since 1862, the 61st New York. Miles wrote, “I rallied a line on this regiment perpendicular to the line of works, forming it as well as possible under fire.” Personally leading the regiment, Miles was able to save one battery of the 12th New York Light Artillery and stem the Confederate tide. With other rallied men, Miles acted as a plug in the Confederate breach.[xviii]

Miles’ ad hoc force managed to hold onto nightfall and then cover the Second Corps’ withdrawal from Ream’s Station back towards Globe Tavern. The Federals had left the battlefield by 7 PM, when a heavy rain began falling over Ream’s Station.[xix]

August 25 had been, without a doubt, the worst for the once vaunted Second Corps. The day had created 2,602 casualties for Hancock, nearly 40% of his force. Of that figure, 1,968 had been captured.[xx]

But worst of all, and most embarrassing to the corps, was the loss of twelve regimental flags and nine pieces of artillery. When one remembers that the Second Corps did not lose its first cannon of the war until the Battle of Spotsylvania, Ream’s Station hit the men especially hard.[xxi]

For his gains on August 25, A.P. Hill reported 720 casualties.[xxii]

The famed Second Corps was gone. Its heavy use throughout the Overland Campaign had shattered it, leaving a shadow of its force incapable of stopping attacks like those at Ream’s Station. In his trilogy of the Army of the Potomac, Bruce Catton described the fighting as, “[M]en running in panic from a Rebel counterattack which the old [Second] Corps would have beaten off with ease.”[xxiii]In his postwar history of the corps, Francis Walker bemoaned, “Could the killed and wounded… of but one-half hour’s fighting at Cold Harbor have been called back to the Second Corps on the afternoon of the 25th of August, Heth might have charged till the sun went down, and all to no purpose…”[xxiv]

Heth himself would write, “I have read that if Hancock’s heart could have been examined there would have been written on it, ‘REAMS’, as plainly as the deep scars received at Gettysburg… were visible.”[xxv]

The Second Corps would continue fighting until the bitter end in April, 1865, to prove that “Ream’s Station was but a nightmare and a hideous dream.”[xxvi]

________________________________________________________________________________________

[i] Lawrence A. Kreiser, Jr., Defeating Lee: A History of the Second Corps of the Army of the Potomac (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2011), 207.

[ii] Francis C. Barlow, “Fear was not in him”: The Civil War Letters of Major General Francis C. Barlow, USA, ed. by Christian G. Samito (New York: Fordham University Press, 2004), 213.

[iii] Francis A. Walker, History of the Second Army Corps in the Army of the Potomac, (New York: Charles Scriber’s Sons, 1886), 581, 583-584.

[iv] Official Records of the War of the Rebellion (hereafter cited as OR), Series 1, Vol. 42, pt. 2, 449.

[v] Walker, 603.

[vi] John Horn, The Petersburg Campaign: The Destruction of the Weldon Railroad, Deep Bottom, Globe Tavern, and Ream’s Station: August 14-25, 1864 (Lynchburg: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1991), 123.

[vii] Edwin C. Bearss, and Bryce A. Suderow, The Petersburg Campaign: Volume 1, The Eastern Front Battles, June-August 1864 (El Dorado Hills: Savas Beatie, 2012), 357.

[viii] Noah Andre Trudeau, The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864-April 1865 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1991), 181-182.

[ix] Walker, 582.

[x] Miles’ Report, OR, Series 1, Vol. 42, pt. 1, 252.

[xi] Bearss, 373.

[xii] For Hill’s health see: James I. Robertson, Jr., General A.P. Hill: The Story of a Confederate Warrior (New York: Vintage Civil War Library, 1987), 299. For the discrepancy in the number of guns that Pegram brought with him to Ream’s Station, see: Peter S. Carmichael, Lee’s Young Artillerist: William R.J. Pegram (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1995). Carmichael says 17 guns, 138; John Horn agrees, also saying 17, 154; Trudeau says 12, 186; as does Bearss, 379.

[xiii] Earl J. Hess, In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications & Confederate Defeat (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 137.

[xiv] Horn, 133.

[xv] Henry Heth, The Memoirs of Henry Heth, ed. James L. Morrison (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1974), 195.

[xvi] Kreiser, 208.

[xvii] David M. Jordan, Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996 paperback edition), 162.

[xviii] Miles’s Report, OR, Series 1, Vol. 42, pt. 1, 253.

[xix] Horn, 170.

[xx] OR, Vol. 42, pt. 1, 130.

[xxi] Gordon C. Rhea, The Battles For Spotsylvania Court House and the Road to Yellow Tavern, May 7-12, 1864 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2005), 138.

[xxii] Hill’s Report, OR, Series 1, Vol. 42, pt. 1, 940.

[xxiii] Bruce Catton, Bruce Catton’s Civil War: Three Volumes in One (New York: Fairfax Press, 1984), 647.

[xxiv] Walker, 605.

[xxv] Heth, 206.

[xxvi] Walker, 606.

My Irish ancestor who earned the MOH at Cold Harbor,lost his life at Reams station on Aug.25,1864!He was a 20 yr.old lad from Ireland,I have often wondered where he was buried,if at all,after the conflict and the Union soldiers fled the area!Only God knows and thats what counts,God rest his soul.He gave his life for his new country!

My great great Grandfather, McCombs Van Houten (spelled Van Houter on his tombstone in Arlington National Cemetery) was mortally wounded at the 2nd Battle at Reams station. He left his wife and his 6 surviving children in the Pittsburgh area.