Almira Hancock: An Officer’s Bride, Adventuress, & Homemaker (Part 2)

She opened the telegram, took a deep breath, and read aloud in a low voice: “I am severely wounded, not mortally. Join me at once in Philadelphia. Parker and Miller, I fear, are gone up.”[i] Wounded, not mortally. Join me at once. The words repeated themselves continually in her mind as she tried to decipher some hidden meaning in the straightforward words. In Philadelphia, at a hospital, no doubt. A hospital? She shuddered at the thought. Join me.

Six year old Ada was crying, and Almira embraced her, speaking comforting words. Russell – her sturdy twelve year old lad – was already scanning a newspaper, announcing the earliest train to Philadelphia. The children would go with her, she decided. If Winfield was more seriously injured than he dictated, she would want the children close by, to see him. Join me at once…there was no time to lose.

Hours later – with trunks packed and tickets purchased, Almira Hancock and her two children waited at the train station. She had braved wilderness frontiers, but until now she had not been required to see her husband seriously injured…maybe dying. She refused to think that. Years before, an older officer had advised her not to allow hardship or fear to break apart her marriage, and she had heeded his wise words. Now, there was no question in her mind. My place is at his side – I am going, she resolved.

When Almira and the children arrived in Philadelphia, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock rested at the LaPierre House on Broad Street, under the care of prominent physicians. He had been wounded during the Battle of Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 3, 1863, just as the Confederates were making their grand charge. It was a nasty injury – the bullet had punched through the wooden and leather saddle before embedding itself and the collected wood and saddle nails in the uppermost part of the general’s thigh. The bullet remained lodged deep in the body.[ii]

Philadelphia was miserably hot. Winfield was feverish, in constant pain, and continually tormented by various skilled physicians who wanted a chance to probe for the bullet. Almira was distressed by the difficult situation and also grew frustrated because her husband did not receive much glory for his crucial role at Gettysburg. However, she realized first priorities were keeping Winfield as comfortable as possible, breaking the fever, and helping him recover; setting the historical record correct would come later. Finally, the general retreated from the heat and doctors, making the journey to his parents’ home in Norristown, Pennsylvania. Almira supported his decision.

In the rural town, the summer weather was more bearable, but Winfield did not recover. The agonizing pain continued. Thin and weak, he hinted at looming death. Finally, a country physician was able to open the infected wound and remove the elusive bullet and chunk of wood. After the operation, Winfield’s health improved rapidly.

When he was able to travel, the family returned to St. Louis. The general received many official letters of gratitude for his wisdom at Gettysburg and regular correspondence questioning when he would return to command. Once her husband was out of the invalid’s chair, Almira noticed that he spent much time out in the yard, trimming the trees and shrubs.[iii] Winfield had always enjoyed gardening, and, perhaps, this time he was also accomplishing something her “to do on military leave” list.

Too soon both for the wound’s healing and for Almira and the children, Winfield reported for military duty. He led the II Corps during the Overland Campaign of 1864 and the Siege of Petersburg before reassignment to recruiting duty.

During the military actions, Almira received regular letters from her general. Often he expressed private opinions of political leaders and other military commanders, his frustration with situations, and his continuing pain from the wound. Almira was his confidante. What he told her would not be leaked to the newspapers. She would keep his opinions to herself and not offer “I told you so” concerning his injury. In the challenging military arena of squabbling generals and vicious political schemes, Almira was the only person Winfield trusted to keep his secrets. Though not exerting a visible presence on the military stage, Almira Hancock’s trustworthy character was essential to her general’s successful career.

At the end of the Civil War, Almira received a message, asking her to come to the new headquarters in Winchester, Virginia, for a visit. On April 15, 1865, while waiting for an escort and a train to make the final stage of the journey, Almira heard the news of Lincoln’s assassination, and, after much pleading with the Secretary of War, finally received permission to take a special train to Winchester. About the time she arrived, Winfield received directions to report to Washington City and restore order. They bordered the train again.[iv]

In Washington, Winfield succeeded in calming the populous and starting a manhunt for the assassins. His role took a more grisly turn when he was ordered to preside over the hangings of the convicted conspirators. Almira defended her husband against harsh critics seeking to defame him for his role in the death of Mary Surrat. Winfield had no part in her trial, assisted her daughter in seeking pardons, and in the end had little choice except to follow orders.

During the years following the Civil War, the Hancock family moved several times as Winfield’s military duties took him to different regions of the country. One assignment – the Fifth Military District of the Reconstruction – was a position that neither Winfield nor Almira found appealing. As a Democratic, Winfield believed the Reconstruction policies were harsh and unconstitutional. Upon arriving at his new post, the general issued Order No. 40, stating that local and state governments would be allowed to function normally and without military interference as long as they abided by the Constitution and acted according to the confirmed laws of their state. The orders were contrary to the radical Reconstruction policy which tended to require the military to control the states and enforce “punishment” on former Confederates.

Almira had heard the first draft of the order after Winfield stayed up all night composing it. She recalled, “I heartily approved, and congratulated him upon the wording of the order. ‘Now’ said I, ‘we will break stones together, should the conscientious reconstructionists use their power against you.’ ‘ They will crucify me,’ he replied… A more grateful people could not be found than the Louisianans and Texans when this order was promulgated.”[v] Winfield and Almira were welcomed and beloved by the Southerners, but their prediction regarding the reactions of the Reconstructioners was correct.

During the two presidential elections prior to 1880, Winfield Hancock had been nominated by the Democrat Party, but he had failed to win the majority. However, ambitious friends determined to make 1880 a positive year by introducing a new era of more honesty, less political scandal, and a popular Union veteran. Initially, Almira was not pleased when Winfield agreed to run for president, if nominated.[vi] By now, Winfield was middle-aged and still a military general overseeing the large eastern district; perhaps she didn’t want him to take on too many responsibilities. Or maybe she was not comfortable with the idea of hundreds of visitors descending on their peaceful New York home, wanting to monopolize Winfield’s time.

He did win the 1880 Democrat Party nomination and his supporters campaigned nationwide, hoping to landslide defeat Republican candidate, James A. Garfield. Almira extended hospitality to the massive numbers of visitors coming to her home, hoping to see the famous general…and petition for government jobs. The campaign season was tiring in a time when both Almira and Winfield wanted privacy. Their grandson died on the day Winfield received the nomination, adding to the grief from their daughter’s death several years before.

In the end, Winfield S. Hancock did not win the presidential election. On election night, he went to bed early while Almira stayed up, waiting for the results. “At 5 o’clock on the following morning he inquired of me the news. I replied, ‘It has been a complete Waterloo for you.’ ‘That is all right,’ he said, ‘I can stand it,’ and in another moment he was again asleep.”[vii]

The following years were punctuated with life’s joys and grief. Winfield read, edited, and commented on various histories of the Civil War, taking particular interest that his II Corps received proper notice. Close family members – including Russell – passed away. Winfield was asked to coordinate General Ulysses S. Grant’s funeral. Friends and Civil War veterans called at the Hancock home frequently to visit and reminisce about the past.

At the beginning of 1886, Winfield began to have serious health issues. In early February, he became feverish and lapsed in delirium. Almira and skilled physicians were at his bedside, but previously undetected medical conditions now surfaced, and the general was too weak to fight for better health. On February 9, Winfield watched Almira and struggled to say what was most important to him. “O, Allie, Allie! Myra!” he murmured, calling her by the names he preferred. “Good –“ Unable to finish his words, Winfield lapsed into unconsciousness and died quietly several hours later.[viii]

Winfield had always been a soldier. The Hancocks had lived solely on a soldier’s salary, paying for their lodging and entertaining expenses. They had little money set aside, and Almira had no children to care for her. It is said that the comradeship of soldiers is unbreakable; for Almira this was a true blessing. Union veterans heard that Mrs. Winfield S. Hancock was in need, and they rallied to her aid, eventually raising $55,000 and giving her a home in Washington City. In 1887, Almira’s book Reminiscences of Winfield Scott Hancock was published. In typical Victorian Era prose, she recounts the story of her general’s life and defends his decisions and actions. She lived in Washington, moved to Europe for a year, and then took residence in New York. When Almira Russell Hancock died on April 20, 1893, she was buried in St. Louis.

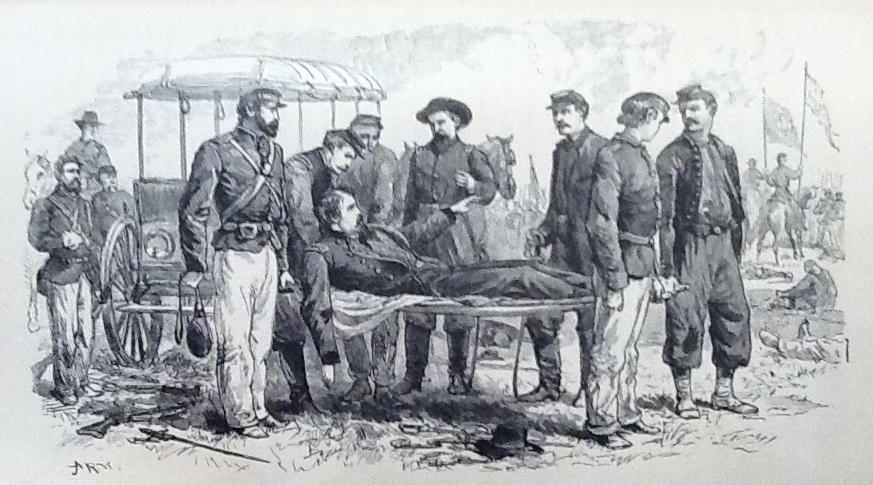

(Illustration from “Life of Hancock” published in the 1880’s)

Some may argue that Almira Hancock did not play a significant role in the American Civil War. She did not volunteer as a nurse. She did not write any known speeches. She did not win a prize for how many stockings she knit. However, Almira faithfully went above and beyond the typical call of duty for a 19th Century wife.

It does not detract from General Hancock’s character to acknowledge that Almira helped make him a successful man. Her faithfulness, wisdom, determination, and domestic skills contributed to his respect among his superiors and peers. In the ancient Proverbs of Solomon, the writer questioned, “Who can find a virtuous wife? For her worth is far above rubies… Her husband is known in the gates, when he sits among the elders of the land.”[ix] Almira Russell Hancock’s life is a positive example of how one courageously faithful lady can stand beside a man of strong character and enhance his success.

[i] A.R. Hancock, Reminiscences of Winfield Scott Hancock, (1887), page97. [Reproduction printing in 1999.]

[ii] D. M. Jordan, Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life, (1988), pages 101-102.

[iii] G. Tucker, Hancock: The Superb, (1960), page 167.

[iv] A.R. Hancock, Reminiscences of Winfield Scott Hancock, (1887), pages 106-108. [Reproduction printing in 1999.]

[v] Ibid, Page 124.

[vi] D. M. Jordan, Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life, (1988), pages 284, 289.

[vii] A.R. Hancock, Reminiscences of Winfield Scott Hancock, (1887), page 172. [Reproduction printing in 1999.]

[viii] D. M. Jordan, Winfield Scott Hancock: A Soldier’s Life, (1988), pages 313-315.

[ix] Proverbs 31:10, 23, New King James Version

From what I have read, I do not think General Hancock was either “welcomed” or “beloved” by the people of the South during Reconstruction. No matter how charming the man and his family, he remained a symbol of oppression to those who lost the war. We shouldn’t forget this, I think.

I suppose it would depend on which primary sources are read. Certainly as “the guy in a blue coat” Hancock was generally viewed as part of the Reconstruction armies and therefore not popular. However, it was interested to read about his attempts to restore peace and allow *state governments* to really restore order and a level of normality. Strange as it sounds, General and Mrs. Hancock were respected and welcomed by quite a few Southern families and they made some good friends. Order No. 40 went a long way in establish better relations. I didn’t intend to paint a rose-colored picture of the Reconstruction and to do the Hancock/Reconstruction situation full justice would probably take several more blog posts. 🙂

The Federal Government was remiss in its obligation to hang every confederate who took up arms against the United States of America. The list of the treasonous confederate criminals include Jefferson Davis and the inept General Robert E. Lee.

Gen. Hancock was dead wrong in his opposition to efforts to make right the 150 years of rape, murder and kidnapping of African Americans by Caucasian Americans.

Why wasn’t Mrs Hancock buried with her husband and daughter in Norristown PA ?

Hello Sarah

I am a reenactor and I portray Winfield Scott Hancock, so I have been researching him and his family, I had not found much about Almira just odd bits until I found your part 1, I have been searching for part 2 and have found it now, i have taken the liberty of printing part1 and 2 of so that i may study it and show the lady who enacts her part when we are together.

thank you for your VERY interesting posts.