A Mother’s Influence

“What will Mother say?” “Oh, how shall I tell his mother?” “Dear Mother…” The maternal parent is certainly one of the most mentioned figures in the letters, music, and battlefield cries of Civil War soldiers. With guiding influence from infancy through youth and into adulthood, mothers of mid-nineteenth century America held feminine and maternal power over the lives, thoughts, and actions of their sons. They understood that influence, taking their responsibilities seriously and raising a generation of men whose leadership was renowned in politics, on the battlefield, and in the postwar era.

Following Judeo-Christian values, American thinking in the early and mid-nineteenth century had clearly divided the roles for men and women. Men were the leaders, protectors, and providers for the family. Women were the homemakers, nurturers, and teachers. These “spheres of influence” were the bedrock of the family unit, and women held great influence, though not in publically visible roles. The adage “the hand that rocks the cradle, rules the world” applies to women of the Civil War era. Controlling home life, managing farms or businesses, and training the next generation of American citizens, women exerted great power within a feminine framework on all social levels. Certainly, this norm of housework, childcare, and hospitality did not appeal to all women, but the majority embraced their role, rejoicing in the subtle authority they achieved from their home and family life.

The guidance, wisdom, and stability of a mother was both an accepted part of society and crucially important to the youthful development of the children. Undoubtedly, daughters were important family members, but sons often took the more visible roles in society and reflected their character and mother’s influence in a public setting. From crying infant to college lad, a mother watched, directed, and molded the character of her son, often according to religious beliefs. Fathers had great influence in the lives of their children, but were typically not as directly involved in some of the most formative training of a child’s character. Tending to his childish needs, rejoicing in his youthful achievements, reprimanding his misconduct, and praising worthy role models, Mother led her son toward a path of success. A solid platform of good morals was key to the idea of the “self-made man” – though, ironically, that “self-made man” probably received the key elements of his success from his mother’s teaching or guidance. Abraham Lincoln – an ultimate example of the “self-made man” – admitted “all that I am or ever hope to be, I owe to my mother.”

Aside from providing guidance for good morals, one of the greatest ways a mother influenced a son was through simply listening and then responding with kindness and perhaps advice. Significantly, grown sons wrote to their mothers from colleges, job locations, and military camps, seeking guidance or opinions on various social, religious, or moral topics. Some letter collections reveal mothers giving advice only when requested, while others – probably in an attempt to “help” – sent overabundance of counsel which probably caused the recipient to role his eyes. (Really, Mom? Yes, of course I remember to change my stockings and shirt every day in a military camp and wash them too…)

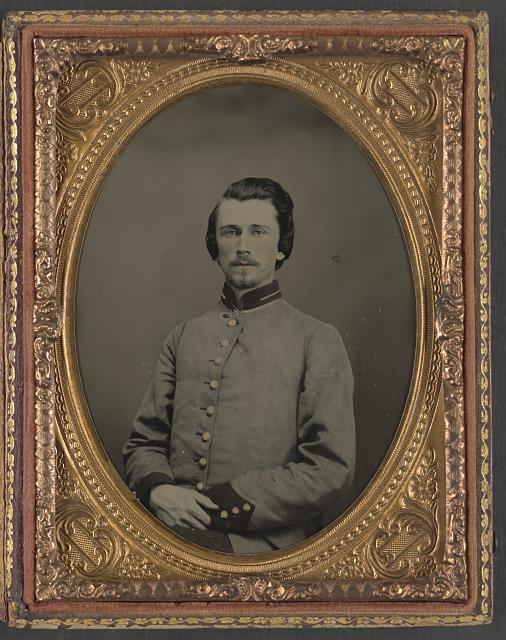

Some sons sought advice on enlisting in the army during the Civil War. Oftentimes, their letters are a rationalization of their reasons to fight, ending with statements assuming or asking for Mother’s approval. Other times, mothers received letters begging for forgiveness for enlisting without her approval and then listing the justification for disregarding her wishes. Whether a mother promoted her son’s decision to enlist or hated the thought, the principles she had instilled usually led to his choice. If he fought for the ideal of union or theory of state’s rights, it was because she taught him the grandeur of America’s past and expected him to be a worthy citizen. If he battled for abolition, it was probably because she had instructed him to protect the helpless. If he marched to war to defend his invaded homeland, protecting his mother (and other family members) was often forefront in his mind. From childhood, mothers had encouraged the manly characteristics and ideals which, ultimately, made their sons battlefield warriors.

Soldiers wrote thousands of letters home. If they couldn’t write, they often tried to find someone else to write for them. Whether he was an enlisted man or an officer, most soldiers took time to write to Mother. It is interesting to observe changes in the letter-writers’ styles and subject matter when writing to their mothers. Usually, the style is the best the man can write and the content generally takes a reassuring tone. The soldier might confess his escapades in camp to his brother or possibly write shocking battlefield details to his father, but most letters to Mother focused only on positive (or at least not too unsettling) details, thanks and requests for items, assurances that he will make it through the war, promises that if he doesn’t live he will see her in heaven, and the ever-present declarations that she must not worry.

The generation of men – young and old – who fought the Civil War knew what it meant to “act like men.” However, it wasn’t a theatrical act. The principles of strong character, moral behavior, and unflinching sense of duty were an un-separable part of their lives. Whether they were “self-made men”, chivalric dreamers, or sturdy workers, these men knew what it meant to value home, honor, and country. Their mothers had taught them well.

In the nineteenth century, “Mother” was a beautiful word, a respected title. After all, the person who loves, inspires, and guides a child will have the ultimate privilege of shaping their life, thoughts, words, and actions. May we all remember this simple truth.

Nice job, and perfect timing! My wife enjoyed it too. I think it was Bell Wiley, who wrote about soldiers throwing away their playing cards before a battle. The reason was that if they were killed, and their effects sent home, they would not want their mothers to know they had been playing cards and gambling!

Glad you and your wife enjoyed the article. Yes, I’ve always been amused by the “discarded” playing cards too – the irony comes after the battle, when the survivors find, purchase, or make another deck of cards. They didn’t want mom to know, but weren’t really interested in “repenting.”

Yes, they were not about to repent, they just did not want to get caught! I am reminded that my paternal grand parents thought that playing with cards was sinful.